A Flare Amidst the Rubble

In our first instalment of “Stopped in My Tracks”, a new series in which a contributor reflects on a life-altering encounter with an artwork, Carly Lewis discovers a sense of regeneration in Judit Reigl’s Guano.

Ten years ago last July, a friend I’d known since middle school died in a car crash. It happened on a two-lane highway in the early afternoon, when he collided with a dump truck, the only other vehicle on a long stretch of empty road. He was pronounced dead at the scene. Something cardinal shifted in me when I found out, and never really slid back into place. This is a gentler way of saying I went crazy, though my downswing had already begun.

Two weeks before the accident, I’d fallen in love with a man who would spend the next half-decade tormenting me. Three weeks before, I’d agreed to a dubious book deal with a small Canadian publisher—60,000 words for $3,000. My first draft, thankfully never submitted, was due only a few months from signing the paperwork.

All to say that ten years ago last July was the start of my great tumult. The anniversary and its attendant realizations—of what’s stuck with me and what hasn’t; what I’d like to keep, what to forget—loomed in my mind this past summer, as I swam across a lake, fixated on the splurge of my limbs making exalted little waves; drank chilled red wine outside during heat warnings, overdoing it just enough that a tepid breeze or unhealed memory might make my eyes water at the table in view of sweaty pedestrians; watched friends get married, a photo of the bride’s dead father tucked in her bouquet; and sang karaoke in a clammy basement bar, knowing my friends and I might catch the potentially fatal virus still circulating the globe. I maxed out a credit card in Montreal, in a daze.

When I arrived at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, it was packed with tourists in town for the long weekend. I assumed my time there would be more of a stride than a slow, thoughtful stroll, with so many people clustered around each piece. My mind wandered back to the car crash, how my brain scrambled when I got the news, how I dried my tears with an abrasive Ikea hand towel, and went to work the next day in the outfit I slept in, the same outfit I wore to work the day before, what I was wearing when I answered the phone.

Losing my lucidity to an undertow of sadness, I gravitated to one of the gallery’s benches. Before I could sit, I was stopped short by what looked like a glistening altar in muted pastels, blush-toned ghosts emerging from the floorboards to say hello.

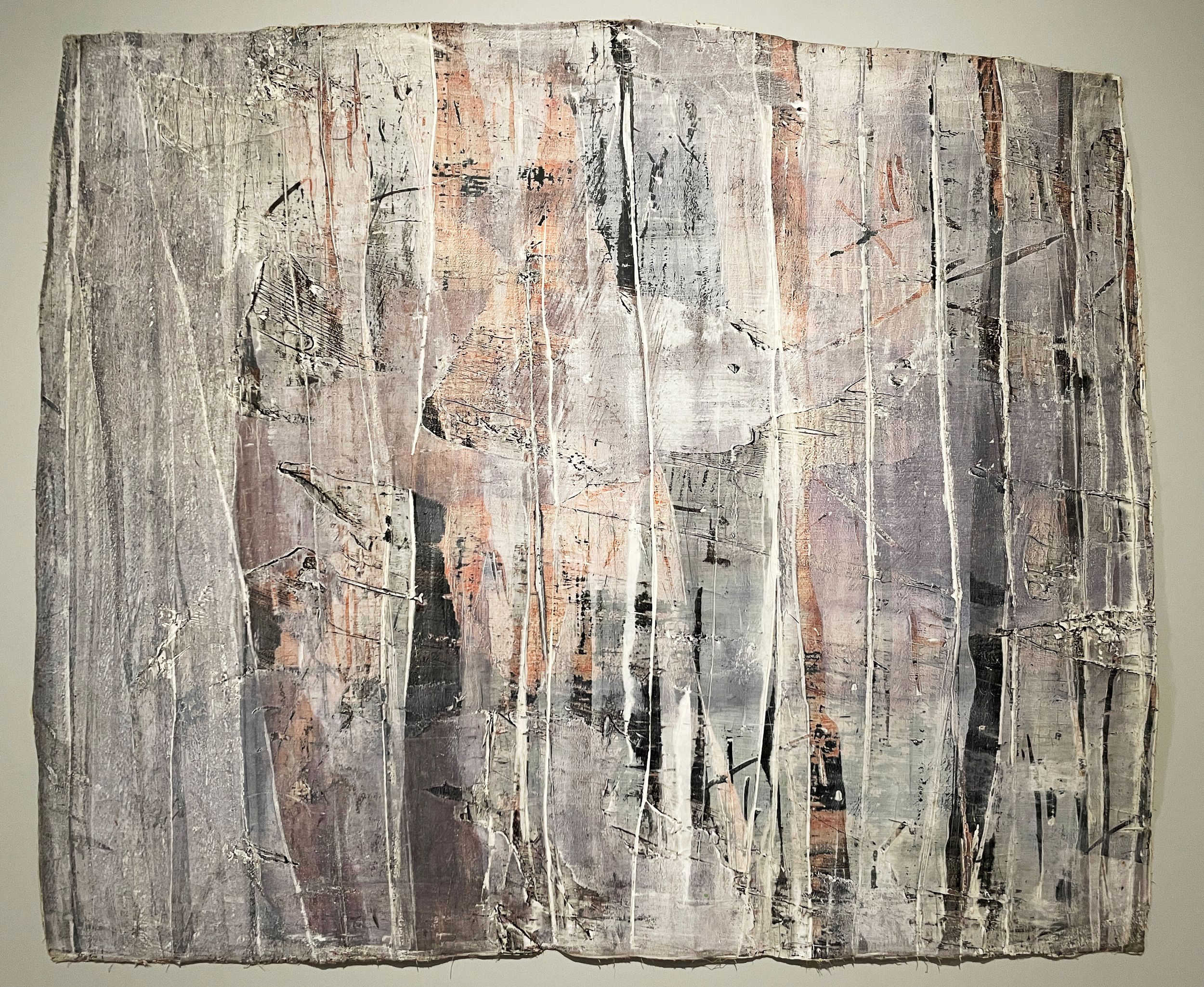

The painting I found myself staring at was called Guano, from a series of abstracts of the same name by the Paris-based Hungarian émigré Judit Reigl, made from what were once discarded canvases she’d laid on her studio’s wood floor to protect it from paint splatter. It was while working on her Mass Writing series in the late 1950s that Reigl saw in these rejected canvases-turned-drop sheets the basis for a new body of work. “Completely ruined as paintings,” she wrote, “they excelled in their very self-negation, becoming fertile ground.” She named the series for the seabird excrement used as fertilizer by Peruvian farmers.

Reigl scraped some of the old paint away, revealing ingrained lines, textures, and tones, fragments of what she had done in the past while her body and mind were elsewhere. She never intended for the falling beads of paint to become their own declaration. But years later, here they were, preserved as proof that everything is soaking in, all the time—morphing, moving, informing, becoming other possibilities, never shifting back to what they were before. As the museum label for Guano explained, “by reworking the deposits on them and scraping sections off, [Reigl] uncovered layers of previous existence.”

Up close, those layers of previous existence appear etched right into the canvas, a palmistry of the self—the filigree of lines, creases, gullies, and imprinted wood grain registering both the passing of time and Reigl’s presence within it. Backing away, the impression is softer, with a sagacious quality, the strips of warmer colour beckoning like a dock one might swim back to, exhausted, from the other side of a lake.

Taking in Guano, I remembered a line by Simone de Beauvoir from her novella “The Age of Discretion,” included in The Woman Destroyed: “Unlooked-for fruit will come from this slow gestation.” There, De Beauvoir’s narrator distills the meaning of the Paul Valéry poem “Palme”, part of which reads:

Patience and still patience,

Patience beneath the blue!

Each atom of the silence

Knows what it ripens to.

In its use of techniques dictated partly by chance (the unplanned paint splatter as by-product of previous work), Guano was an extension of Reigl’s earlier experiments with automatism—an approach that demands patience and trust in the process. Except, by deliberately stripping away and reworking, Reigl was pursuing something more like regenesis than abstraction; turning that which she could not control—what had been “ruined”—into a kind of documentary assertion of the past, and her acceptance of it. (I can almost hear Taylor Swift singing, during the long, quiet coda of her 2022 remake of “All Too Well”, “I was there, I was there,” as though the only willing witness to an otherwise abandoned love.)

Details from Guano by Judit Reigl.

After Reigl’s death in 2020, an obituary in The Guardian recalled that when Reigl was finally able to flee Hungary for Paris in 1950, after eight failed attempts to escape the Iron Curtain, “She walked over a minefield at night, with the aid of a ladder placed on the ground, hoping to reach the express train from Budapest; the small yellow-orange squares of light, flashing in the blackness, signalled future safety. They would also appear as flashes within the broad black swathes of her future paintings.” The physicality of her presence is central to much of Reigl’s oeuvre. Ahead of a 2005 lifetime retrospective of her work in Budapest, Reigl told an interviewer, “My entire body took part in the work, in the wake of my arms wide open.” I think of Reigl walking, resiliently seeking freedom on foot. And I think of her stepping around her studio, safe but resolute all the same.

The distant mourning that felt so palpable in front of Guano had me contemplating the blessing of regeneration—how fortunate a thing it is, to salvage the past if you have the time and tenacity. Reigl saw a use in the worn, brindled floorboards she had worked and walked on, as confirmation that she’d been there. If by some malfeasance or accident her paintings had disappeared forever, the floorboards would still know what she’d made.

Maybe on that day in Montreal, I had seen something particular in Reigl’s painting. How its loamy pinks seem to materialize out of its grim grey textures—both colours accidental in their making—the way a heart regenerates after calamity, a flare amidst the rubble. I hoped that’s what I had now.

“Stopped in My Tracks” is an ongoing series in which an Arcade contributor reflects on their encounter with an artwork that altered their perspective.