All Caught Up in the Infinite Middle

Tia Glista unravels the Möbius strip of narrative in Catherine Lacey’s latest book—a hybrid of memoir and fiction, about a recent break-up and an earlier loss of faith—and reflects on her own break with God, and what faith means in the first place.

1.

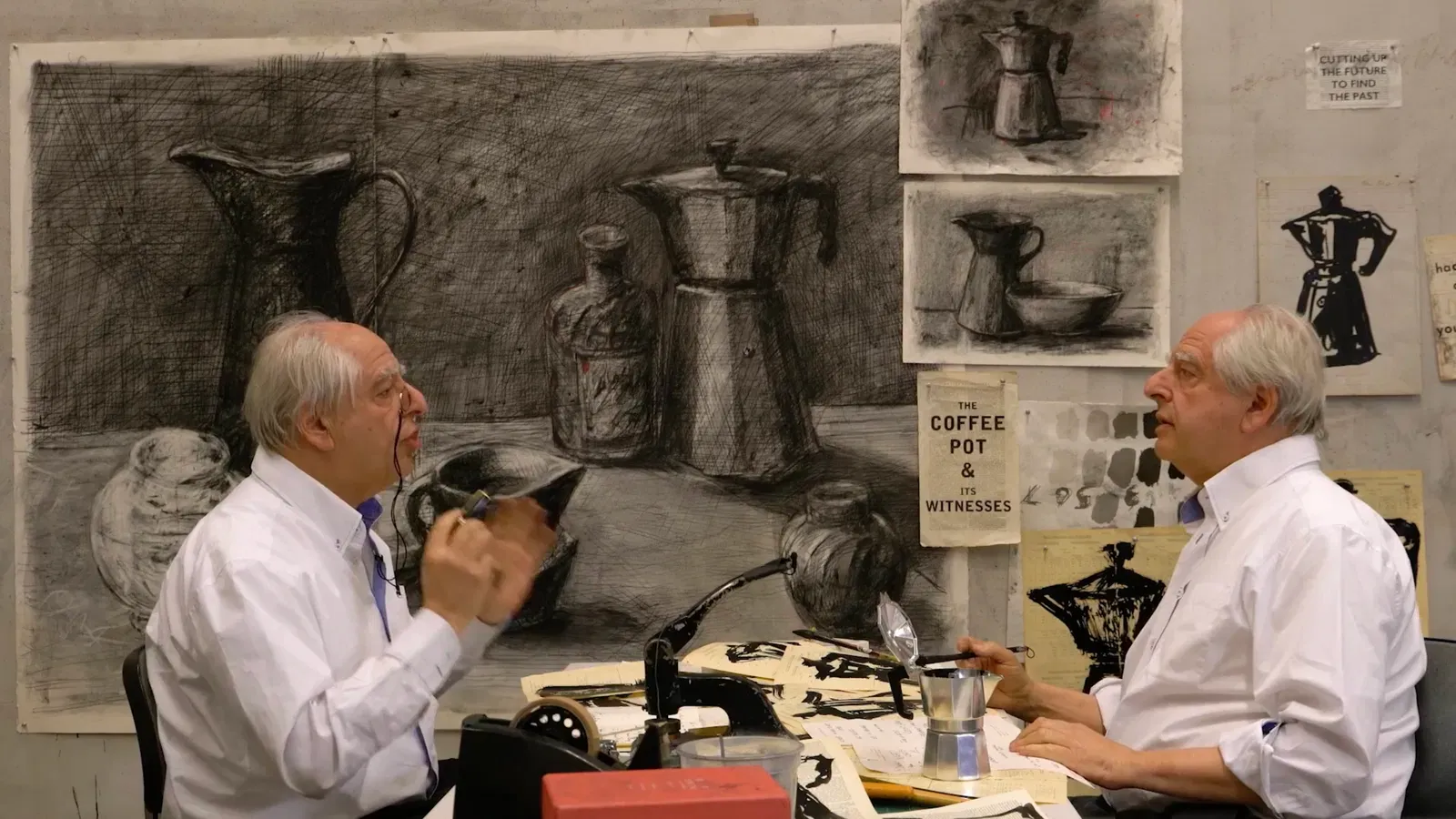

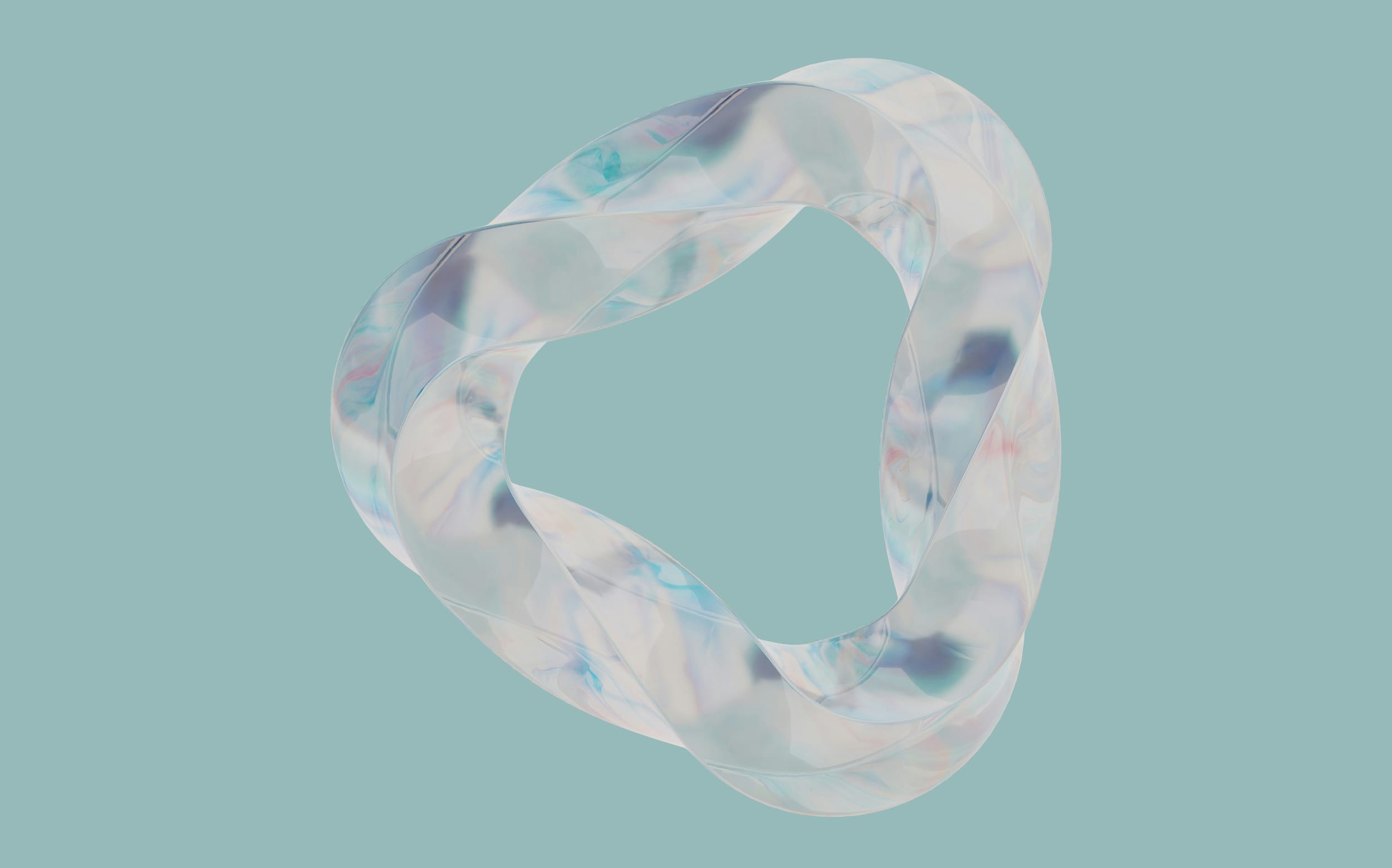

Catherine Lacey’s The Möbius Book is partitioned into two halves: like the mathematical object for which it is named, one is meant to flip the book over and begin anew, following the narrative as it pivots from nonfiction to fiction (as I read it), or vice versa, depending on where you have begun. The conceit is that certain kinds of writers are wont to become obsessed with “bottomless questions,” avoiding the neatness of endings that purport to cauterize the chaos and tumult of life. Instead of ending, the same problems get turned over again, recto verso. Lacey writes:

“I met Avery at MoMA to see a Matisse exhibit, and she asked me how writing was going, and I asked her how writing was going, and we both admitted it wasn’t really going so well lately. Our trouble was a shared one: we were looking for endings but all we could find was more middle. It was hard, we agreed, to find satisfying conclusions to stories that weren’t exactly stories but rather a set of prompts that resisted completion, a Möbius strip of narrative.”

For her obsession with middles, however, or her sense of being stuck in them, The Möbius Book is, on its surface, about endings. Lacey is responding to the end of a six-year relationship, in which the partner for whom she had previously left her ex-husband one day abruptly broke up with her over email from the next room. Wrecked by her sudden ejection from the life that they had built—leaving the house, his mother, their friends, their dog—she squats with friends across the U.S., Mexico, and Europe, hollowed out and upended. To say that she is sent reeling might default to certain clichés, but in this case it is true: the nonfiction half is rootless, never quite settling down as she becomes itinerant, yet always affixed to this stinging loss.

The narrative travels in not just space but time, as for Lacey this period of upheaval is comparable to another break-up from earlier in her life—her break-up with God. Following a strict and devout Southern upbringing, disbelief leaked into her life at the beginning of college. Then and now, she finds herself adrift from a male authority who gave her life structure and meaning, who told her what to think and believe, who acted as a kind of shelter. In both cases, she responds to the severing of the bond by ceasing to eat: “Hunger was the closest ancillary I had to the rapture I'd felt when I went to the altar as a kid with open palms at weekend retreats [...] Hunger was a pure devotion to the nonmaterial, and its hollow suffering felt like an act of faith, a denial of the world as I waited for heaven.” She scoops herself out, subtracting in order to abstract reality, to slip away from confronting what she has lost.

What this all amounts to is often engrossing, though not always clear, nor ever condensed into a precise, unified argument (alas, more middle). The Möbius Book is described as a book about faith, however: the faith in others that allows us to rest and see a future in them, and the perplexity of coming to live without these kinds of guarantees. But as someone who has experienced my own loss of faith, I find Lacey’s use of the word inappropriate to describe her fixations, given that it implies a belief in something that is not stabilized and requires trust—even courage—in the absence of proof and sureness.

Rather, Lacey’s touchstones are often material, even paternalistic, comforts: being a homeowner (in a historic Chicago house with three bathrooms and a garden, that she renovates with built-in bookshelves, “the sign of someone who isn’t moving anytime soon”), a boyfriend whose physical aggression she excuses and at times takes refuge in, a muscular stranger who carries her home after a childhood bike accident, esoteric healers and fortune-tellers who can serve up the future on a platter, and of course, divine, Biblical laws that assure redemption and everlasting peace. And so while the book tracks her uncoupling from the stable trappings of normative, middle class life, it does not suggest any loss of attachment to them. Instead, like a Möbius strip, her patterns and proclivities are redoubled; old desires find new homes. It is not really a book about a loss of faith then, but faith’s dogged persistence (or perhaps, trauma’s).

This is most transparent when Lacey compares her ex-boyfriend with Jesus. Both possess a kind of cult-like charisma. Her ex is said to attract a series of devout female students “without seeming to even try; so compelling were his diatribes and pronouncements that it was difficult to resist the conclusions he made about how to live, how to write, how to think.” It becomes easy for her to organize herself around him too. Lacey indulges in certain epistemological pleasures: she knows what their lives will look like (or thinks she does) and enjoys the ways in which he can tell her what she does not know, even that which she does not know about herself. “Like everything he told me about myself, I tended to believe he was right, that he knew me better than I knew myself, as he seemed to know everyone better than they knew themselves,” she writes, after he tells her they are breaking up because he believes she is a lesbian. In this vein, she is made in his image, though also ultimately acknowledges that they had “hallucinated each other.”

Wry Messiah comparisons aside, Lacey’s comfort in the certainty her ex embodies does seem like a naive way to experience a relationship, given that compromise, change, and conflict are unlikely to be a matter of “if” but “when.” It is, her characters in the fictional half admit, correlative to the innocent pleasure of childhood, where problems and crises are not so scary because we know someone else will handle them for us. She facetiously refers to her ex only as The Reason, capital letters inflecting his God-like presence, and perhaps signalling her continued belief in his responsibility for the shape of her life even since their break-up. (If one bothers, it is very easy to find out that The Reason is the writer Jesse Ball.)

Ironically then, one might feel that Lacey’s faith has been placed, above all, in the possibility of assurance, that which seems to be in turn undermined by faith’s unverifiable character. In the wake of her split from The Reason, everything has a potentially explanatory effect, from the appearance of a stray cat on her porch, to a demon allegedly exorcized from her leg. She becomes entirely devoted to reading the signs and recomposing a picture of her life that will make sense—a pursuit for which she seemingly has endless resources and access to space, listing a “friend's guest room, hotel bed in Manhattan, K-town sublet, Oaxacan beach, modernist cabin in Switzerland” as retreats for her recovery. Questions of labour or futurity are deferred for an emphasis on the past and the present, a privilege that might in turn defer some readers’ potential empathy. In the era of the much-publicized women’s divorce novel, The Möbius Book feels incredibly inward-looking, not bound for the kind of transcendent, collective awakening spurred by something like last summer’s All Fours phenomenon. Shit happens, and sometimes, I don’t think it’s as meaningful or necessary to unpack or read about as Lacey does.

And that’s fine, just fine.

I have often felt that Lacey’s writing is projecting toward a very special, brilliant star, of which it always falls just a tiny bit short. Reading 2023’s Biography of X, I was completely enraptured by the opening pages and its ambitious premise—a biography of a fictional performance artist, based loosely on a cobbled-together archive of real figures, set in an alternative 1970s U.S. reeling from the South’s Christian-nationalist succession—but felt it lost its gleaming prose and velocity somewhere about a third of the way in (stuck again, one might point out, in the middle). Perhaps, as Lacey writes (so elegantly) in The Möbius Book after examining a collection of expensive kitchen knives, “it must be one of the most difficult tools to keep sharp over time, awe, a faith in finding the beauty of anything.” It is in turn such glimpses of awe offered by her writing that sustain my weary faith, ploughing on through the next book. I love Lacey’s ambitious quest to tarry with—and leave unsettled—big, “bottomless” questions, though just because some questions are bottomless, does not always make them profound.

This feels even more true of the fiction portion in The Möbius Book in which Lacey stages a conversation between two friends spending Christmas together after their respective break-ups. Marie and Edie’s ruminations about life and love—”there is no story that does not lead to another story”—are more therapeutic for the characters than enlightening for the reader. Maybe this turning over of the same ideas, this patient dwelling in the middle, should tell us something about the effort to organize the chaos of life, where the quest for a stable ending is a fruitless project—one that produces more middle, which can either be a place to get stuck, or a site of relief from the pursuit of certainty. The Möbius Book chooses the former.

2.

I experienced my own loss of faith as a child, though my faith was mostly limp and tenuous compared to the kind of fervour Lacey describes. In the end, it was a place more than a God that held me in its grip—a summer camp two hours north of Toronto, run by Evangelicals, to which I returned every summer for 11 years. I had been raised in a liberal Christian home, sporadically attending a left-wing, urban Mennonite church in the Beaches, or popping into youth group meetings with friends. But it was at camp where I was temporarily enraptured by God, wondering whether every beam of sunlight in the morning or tingle on my spine during Worship was a sign.

One time, a girl in my cabin lost one of her Crocs, and we prayed that Jesus would reveal himself to us by returning it; when it was found a few days later, we took this sign as confirmation that we had been heard. And just as Lacey finds herself returned to the sense of rapture and devotion by the vertigo of hunger, now every summer, my body still traces circles around memories of camp, brought on suddenly by a whispering breeze on my neck or a certain slant of light through the tops of trees in a forest. I often dream of it vividly, all these years later.

When Lacey describes Godliness as an antidote to the pains of existing in a body—particularly a teenage girl body—I know what she is describing. When I was 13, I fell and broke the bone along the outside of my foot, but the camp nurse did not believe me. (Ironic, I think now, that she could believe so fervently in the invisible, but choose to ignore material evidence of swelling or a persistent collage of purple and green bruises). Often, I would ask my counsellor to go to the bathroom but really went to sit on a boulder overlooking the lake, where I would weep, and then I would empty my mind and watch the water moving, moving, always moving. I wanted to be the water, shapeless, able to slip through people’s fingers without being abjected to form, without being humiliated by my uncouth body. And then I would rest my chin on my knee and look down at my aching foot, all too material, all those capillaries bursting under a veil of skin. This desire to transcend the physical came again during Worship, when the camp band would play Christian rock and we would raise our arms above our heads, spellbound, immaterial, floating on the sound.

I also chased these moments of effortlessness because my faith did not come easily, but took persistent internal cajoling. I believed—probably still believe—in God, but found that my politics increasingly chafed against what sectors of the camp preached, where certain counsellors latched onto a vision of a redemptive, blood-thirsty God and told us not to make friends outside of the church, and girls my age spent weekends at pro-life marches and school breaks evangelizing on missions trips.

When I was 15, I entered the Leaders in Training program, which required that I sign a contract concurring with a “Biblical view of marriage,” meaning I would not support—publicly or privately—homosexuality, divorce, or pre-marital sex. I spent weeks staring at the contract before signing it against my better judgement, holding out faith that this did not represent most of the people I knew who worked there (some of whom had come out to me, or had queer loved ones). There had always been a gap between the camp’s official policy and the people I cared about—and who cared about me—and so I tried to believe that the contract was just a formality.

Faith requires certain kinds of blindness. This is part of its definition, to believe without proof, but it is also something that we do to excise the kinds of knowledge that make this submission less comfortable. We ignore the pricks of insight that prevent us from relaxing into our not-knowing, that take away from the bliss of ignorance.

I didn’t go back to camp after high school, but got a paying job in an office to make money before I moved to New York. That summer, the organization that owned the camp underwent a conservative crackdown, investigating staff who had signed the contract in “bad faith,” who were in fact queer-affirming or queer themselves. Most of my friends were asked to leave or withdrew in solidarity when the summer ended. From afar, I grieved this place that had been a second-home since I was six, to which I would never say goodbye. When things ended, however, it wasn’t surprise that I felt, but resignation; though hindsight may be 20/20, sometimes it is more about forcing us to accept what we already knew. I knew my faith had been like a wobbly chair that needed constant propping up to be supported. I knew that I had stayed because I couldn’t do without the love I had been shown, but this same love had also been mobilized to silence dissent, to make people feel they had to suppress coming to consciousness for the sake of keeping their place in the community.

One moment I often return to, that articulates some of my early separation from the field, happened on my last night as a camper, the year before I signed the contract to become a leader. Us older girls had been gathered in the dining hall, where we sat cross-legged around some candles, and our leaders asked us to go around the circle and share where we had seen God at work that summer.

Everyone seemed to take this literally: Jesus came to them in a vision, He gave them as a sign or guided them to a specific verse in their Bible. They seemed so confident of this visual evidence, their relationship to the divine unambiguous and even incarnate. When it came to me, I stumbled at first—God had never spoken to me, not literally at least, and I had a hard time believing He had deigned to chat so freely with everyone else. Instead, I told them that I believed I had seen God in our community, in my friends, in nature, and in the beautiful memories we had made together—all of these things, though oblique, seemed to me to embody the kinds of mutuality, care, and utopian strivings of what we had been taught was heaven’s will for us.

Everyone listened and then shifted uncomfortably, moving onto the next camper without acknowledging what I had said. I immediately felt shy again, but also frustrated. If this was not adequate faith to them, then we had very different ideas of what faith should be. The politics of looking for evidence, and to whom it was revealed and how it became legible, seemed to be steeped in a very particular orthodoxy I could not get behind. Some campers were so studied and practiced in how they spoke about God that it felt like we were being tested or competing to prove our standing in His eyes or the eyes of our leaders. Their investment in signs and miracles seemed to be more about providing proof of their devotion than proof of God.

I do think there is something holy about the randomness of life—the miraculous subtlety of the little bonds we form with others, the chance encounters, the places we go, the breaths we take. The hand of God may not work in patterns we need to go looking for, but in the everyday gestures that we miss when we do. In her fixation on looking for overt signs of meaning, does Lacey miss all of the quiet ones? Between the lines of The Möbius Book, one might see the everyday richness of the world, which is not an enigma to be decoded, which resists closure and certainty, but asks us only to be open to it, here in the ongoing, miraculous middle.