“All Life Comes from Her”—A Gathering Place for Narratives at the Edges

The fourth Bonavista Biennale in Newfoundland was an exploration of meeting points, of the communal but sometimes parasitic energy that sparks when one place becomes home to another.

In a workshed behind Durdle’s, a shuttered hardware store on a side street in the old Newfoundland fishing town of Bonavista, sits Billy Gauthier’s The Earth, Our Mother, what might be the unofficial centrepiece of the fourth Bonavista Biennale. It’s carved out of a decades-dead skull—4’8” tall, 6’8” wide—belonging to the second largest creature on earth, the fin whale.

Gauthier created the sculpture during the Biennale’s first seven days. It was meant to be moved to a dramatic coastal location once completed, but it proved too fragile to relocate. Now, the shed is its temporary home. As Gauthier writes in his artist statement—six letter-sized pages placed on an old wooden workbench—what wasn’t there in the skull is what spoke to him first: the void for the spinal column and brain cavity. In the empty parts, he saw a place to start.

He carved her a mouth, to give her a voice. He carved her eyes, so that she could see. He carved her nostrils, so she might smell the salt and spruce of the peninsula. But he didn’t give her ears. “It’s us that needs to listen,” he writes.

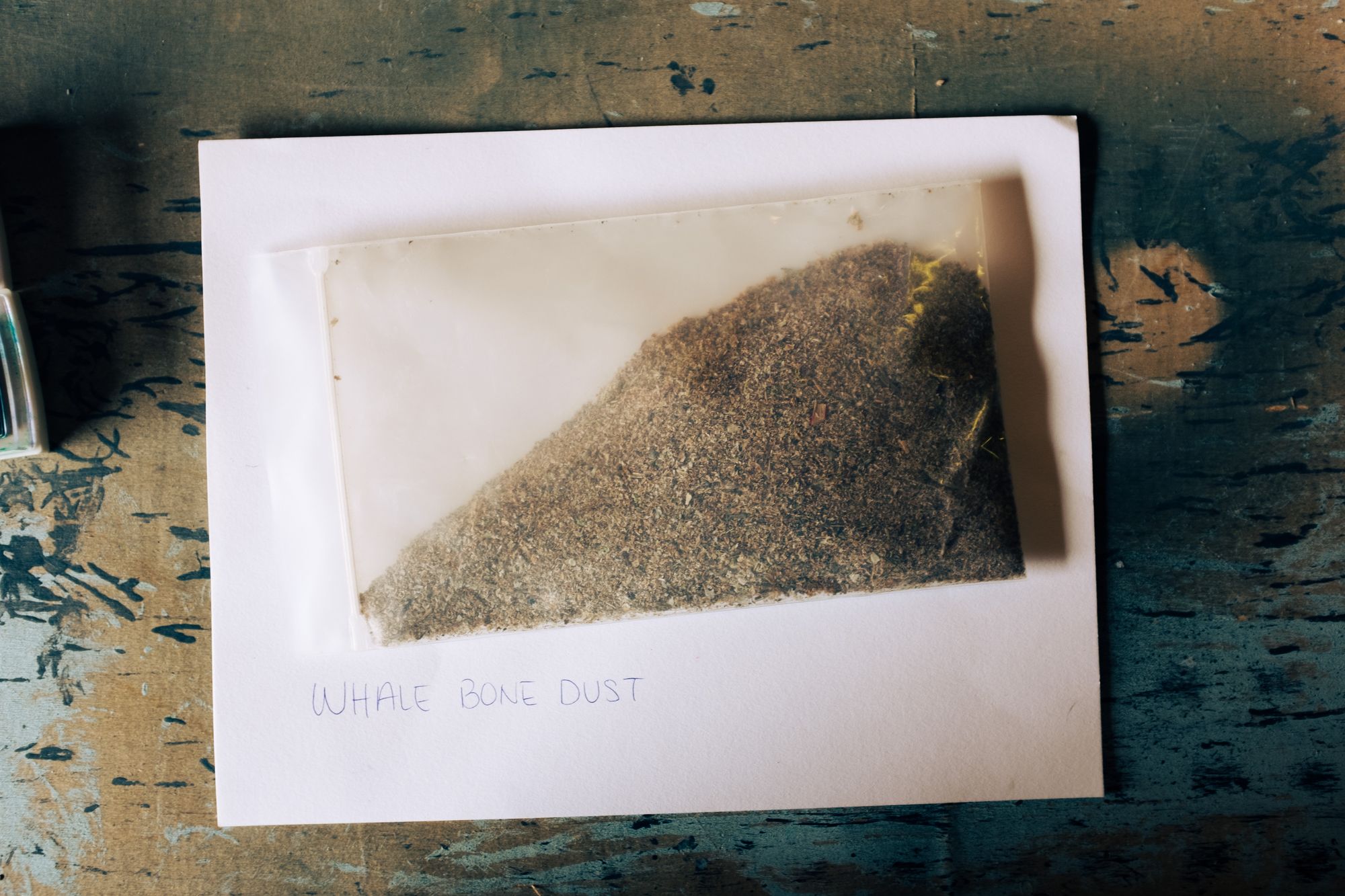

Gauthier’s skull teems with small details of life, from the tunniit on her forehead to the sun and the moon at its extremes. There are hints of the Torngats, of owl feathers. When you walk around it, you’ll see a delicately carved seal at the back, lunging from the mother to feed. The local host looking after the space describes watching Gauthier at work, finding the mother within the skull, as she shows us a bag of bone dust.

“All life comes from her,” Gauthier writes in his statement. The skull lifts something dead into something hopeful—a celebration of what we can still build together.

The mental landscape of outport Newfoundland and Labrador—Ktaqmkuk, Nitassinan, Nunatsiavut, and NunatuKavut—is shaped and eroded, more than any other force, by the waves of loss that still crash over it relentlessly. Those of us who come from here—at least those of us whose ancestors came in poverty to work the fish, off the back of empire—often talk reverentially of old times, how they were taken away as if by surges we had no control over. We do this knowing too of all the other future moments that were stolen away, from the Mi’kmaq, the Inuit, and most fundamentally of all, the Beothuk. In the shaping of our idea about this place, we point to the geological record as much as we do the written and oral ones—our ideas of self wrapped up in the ancient fossils, the first things to die here. We have a tendency to treat landscape as the only museum we have, a fossil to preserve, at the edges of memory.

The Bonavista Biennale is not about that kind of fossilization. Out on this peninsula, a few sprightly months of tourist trade, and a fishery that’s a shadow of what it once was, don’t make up for the decades and centuries of loss and leaving. If you’re going to make a life here, it’s better instead to turn to the energies still humming—the possibilities of what’s still alive, what’s communal, and what can be shared. What, for example, can be offered to those newcomers who arrive with their own traumatic feelings of loss, as they try to make sense of this strange place where they’ve landed.

It’s a set of concerns that’s explicit in this year’s theme: “Host”. Co-curated by Ryan Rice and incoming artistic director Rose Bouthillier, fresh from her previous role at the Remai Modern, the Biennale’s 2023 edition is an exploration of meeting points, of how one place becomes home to another—whether in ways that are welcoming or parasitic. Over the course of two days and hundreds of kilometres, set amidst old buildings and older landscapes, we visit twenty installations that spread play, weirdness, and hard questions, across the outcrops of the peninsula.

At an inactive slate quarry near the town of Keels, SK Maston’s Deep Time Drift (beaks hid in the hole a seal fin, rib bone, rabbit paw fur) overlays rubbings of discarded items from the mine with fossils cast from the peninsula’s rocks on a giant print draped against the quarry’s wall. The reflections of a giant moth, old pop cans and urchin shells are visible in the quarry’s pond, rippling in the ocean wind.

Jessica Winters’ mural Hopedale hangs on the faded exterior wall of a disused fishing premises in Red Cliff, with the spectacular fjords of Terra Nova National Park in the background across the bay. The image charges the contrasts of this spot with a spontaneous joy, emerging, one presumes from her childhood in Makkovik, Labrador—just three kids in hoodies with a puppy, caught in motion against an abstract, icy background, running towards whatever kind of playful trouble pleases them. Further down the road, on the side of an old convenience store, two more of Winters’ murals juxtapose the structures, colours, and life of Makkovik with the struggling reality of this place.

The mural Hopedale by Jessica Winters, at left. Greenland and Perry's Team also by Winters.

On the other side of the peninsula, by the small town of Elliston—still “the root cellar capital of the world”, according to its signage—K. Jake Chakasim’s cliff-top installation Host(age) digs deep below. The structure is an oversized PVC-pipe-supported representation of a sight once common in outports, less so now—the flake used for drying fish in the open air prior to salting. But it also contains elements, according to Chakasim’s text, of Beothuk dwellings and the ship holds that displaced so many against their will. The flake, at this scale, is a shelter. Beneath its crate roof, the Atlantic wind stirs a deeply unsettling lament as it whips through the holes in the pipes, drilled there to keep it from blowing over. But look up under the shelter and there’s a furious history told through collages of colonial documentation, maps and overlays of so many suppressed and misread stories, given piercing but troubled light from the cloudy sky above.

It was at the Mockbeggar Plantation in Bonavista where Camille Turner’s Afronautic Research Lab made a splash with its 2019 Biennale exhibit exploring the complicity of Newfoundland in the building of ships for the Caribbean slave trade. This year at the Mockbeggar site Shelly Niro uses a collection of stretched Hudson Bay Point Blankets—some antique, some freshly purchased—to memorialize a cross-Canadian loss of so much of what made us who we are. The blankets contain representations of material goods traded, from beavers to currency, as well as creatures and resources we’ve taken until there was no more to take. Outside on the lawn, Don Kwan’s This land is my land, this land is your land pulls a series of Muskoka chairs into a circle so tight that no one can enter.

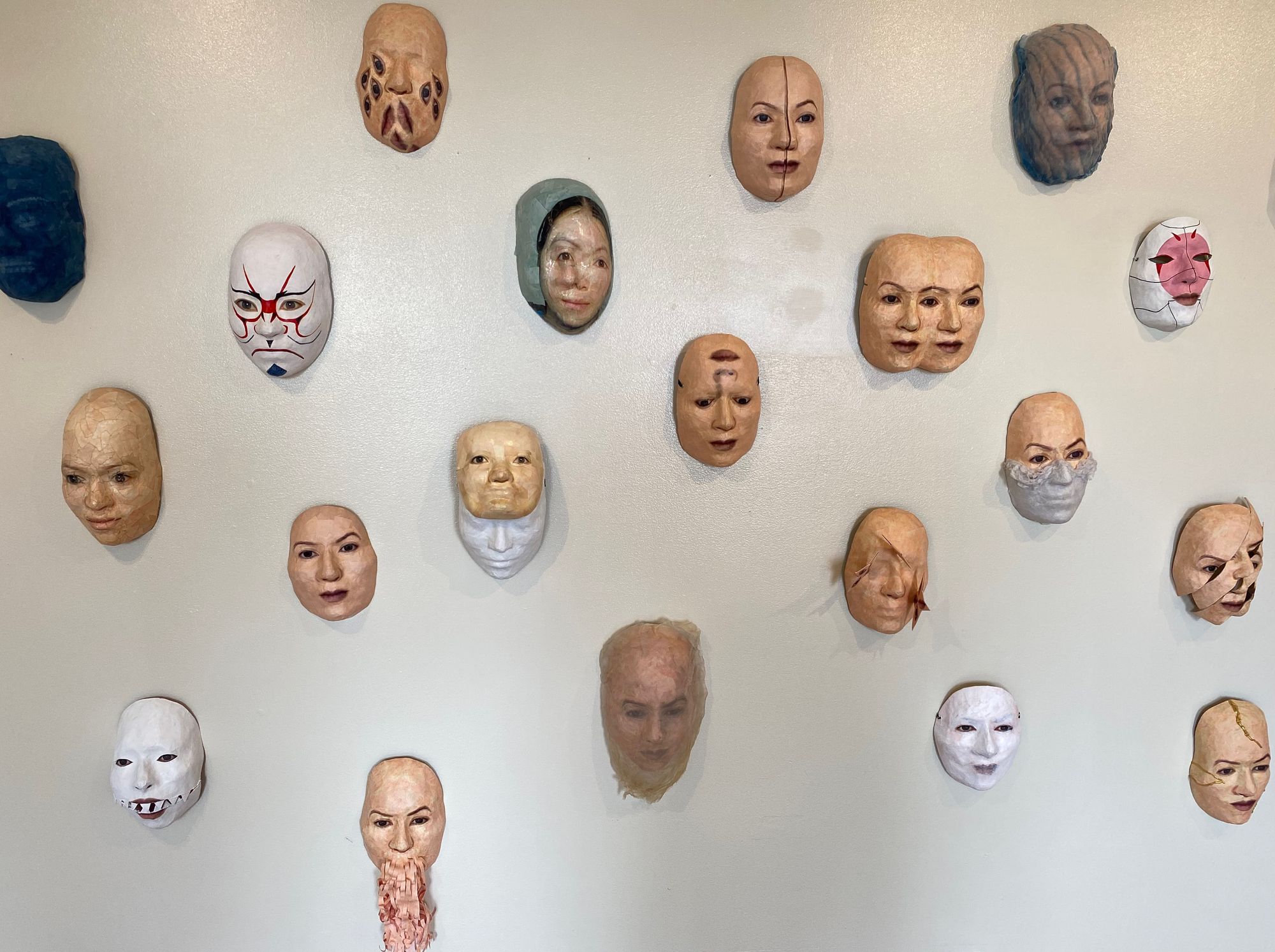

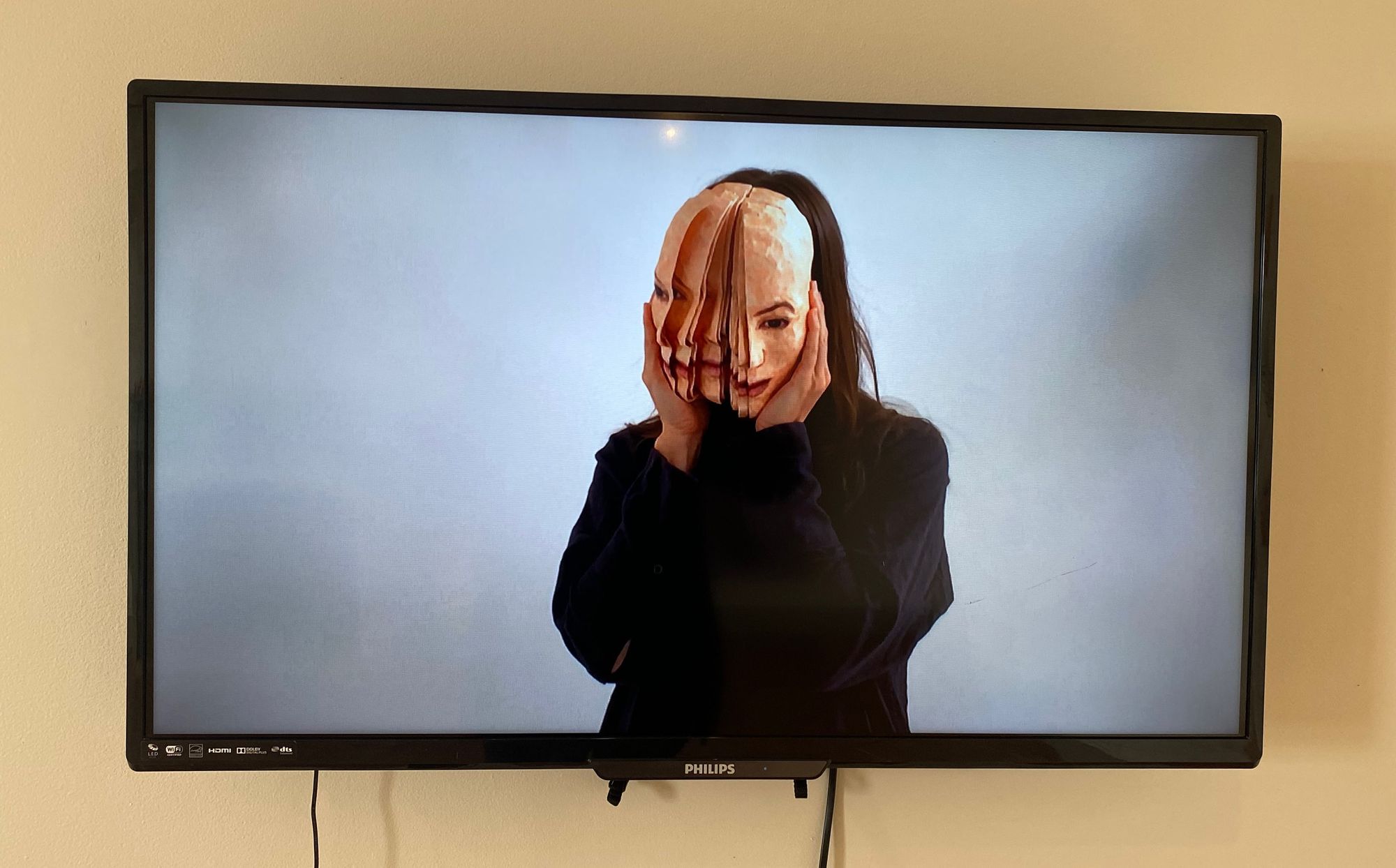

The town of Trinity is the sort of place where it’s hard to tell what’s a film set for a heritage moment and what’s real life. There, Miya Turnbull’s work has taken over the upstairs of a reconstruction of a family home belonging to the operators of the town’s earliest fishing operations. While the museum rooms meticulously recreate one privileged family’s home life—from the old beds to the piss pots—in a town built on hardship, Turnbull’s exhibition, with its overwhelming number of heavily distorted but photo-realistic masks on display, serves as a kind of historical commentary to this sort of reconstruction as identity-making. In the accompanying video, Turnbull applies mask upon mask upon mask to her own face, making any sense of a fixed identity impossible to pin down.

Multiplicity/Fragmentation by Miya Turnbull in the Lester-Garland House, Trinity.

From a drum dance ceremony to the intimate moment shared between what appears to be an infant child and their grandmother, smooshing their noses together in a loving kunik, Mary Ann Penashue’s paintings of life in the Sheshatshiu Innu Nation, on show in the old electric company offices in Port Union, show a joy and vibrancy that the town hosting them hasn’t felt in decades. Canada’s only union-built town is now essentially a living but crumbling museum, preserving on view the glory days of the long defunct Fishermen’s Protective Union. When we get out of our car, a couple of tourists point us to what they presume we’re here for—a viewing area for ancient fossils just off the old boardwalk, behind where the union ran its printing press.

In the room behind Penashue’s paintings, Jerry Evans’ film Mekwe’k L’nu – The Red People overlays the maps and sketches with which Shawnadithit, the last known living Beothuk, documented the memory of her people during her final months—their everyday life, their kidnap and murder—with his own drawings and animations. The legacy of Shawnadithit, and her sketches in particular, is a well-worked theme in recent art from the province. Mireille Eagan’s landmark “Future Possible” curations at The Rooms in 2018 and 2019 placed them at the heart of a vital project to reinterpret Newfoundland and Labrador art history. But the urgency to continue that reinterpretation, in ever changing contexts, will never recede. They are perhaps the foundation document of what we became, and what was not so much lost, but actively destroyed in making us.

At left, a (gentle) reminder by Megan Samms, Port Union. Deep Time Drift (beaks hid in the hole a seal fin, rib bone, rabbit paw fur) by SK Maston, near Keels.

Down by the water, Megan Samms’ a (gentle) reminder flutters in the wind, overlooking the town’s monolithic former fish plant. The flag, hung vertically in Mi’kmaq style, invokes the words of Kwakwaka’wakw artist and activist Beau Dick: “We want to remind you that you are still our guests”. “We are still your hosts” is the rest of that quote, and the declaration on Samms’ flag, already fading in the elements, and deliberately so.

Back in the Union House Arts building, Samms is running an indigo dyeing workshop for visitors and local artists. As we take in Shelley Moorhouse’s textile wall hangings, Bouthillier is proudly holding aloft her own indigo work. Moorhouse’s works radiate and crackle with humour and life, weaving hides and furs with embroidery, buttons and threads, and found objects such as an old SD card. They feel as generous as anything in this biennale—offerings of memory, celebration, and a cherished connection to myth, to land, skies, and stars.

Over coffee in the town of Bonavista, I remark to Bouthillier how striking it is to see this place playing host to these conversations. Bouthillier explains that it was a deliberate choice conceptually to lean into the idea of “and Labrador”, the way one territory is subordinated to another in the province’s name or else often left out entirely. By invoking the exclusion felt by so many in their own province, it was a way of bringing the works into a new context. For an established, senior artist like Moorhouse from Happy Valley-Goose Bay, even this represents a rare opportunity for recognition outside of home. The peninsula feels like it has been turned into a gathering place for narratives from the edges; a gathering that recognizes the glaring absence at its core.

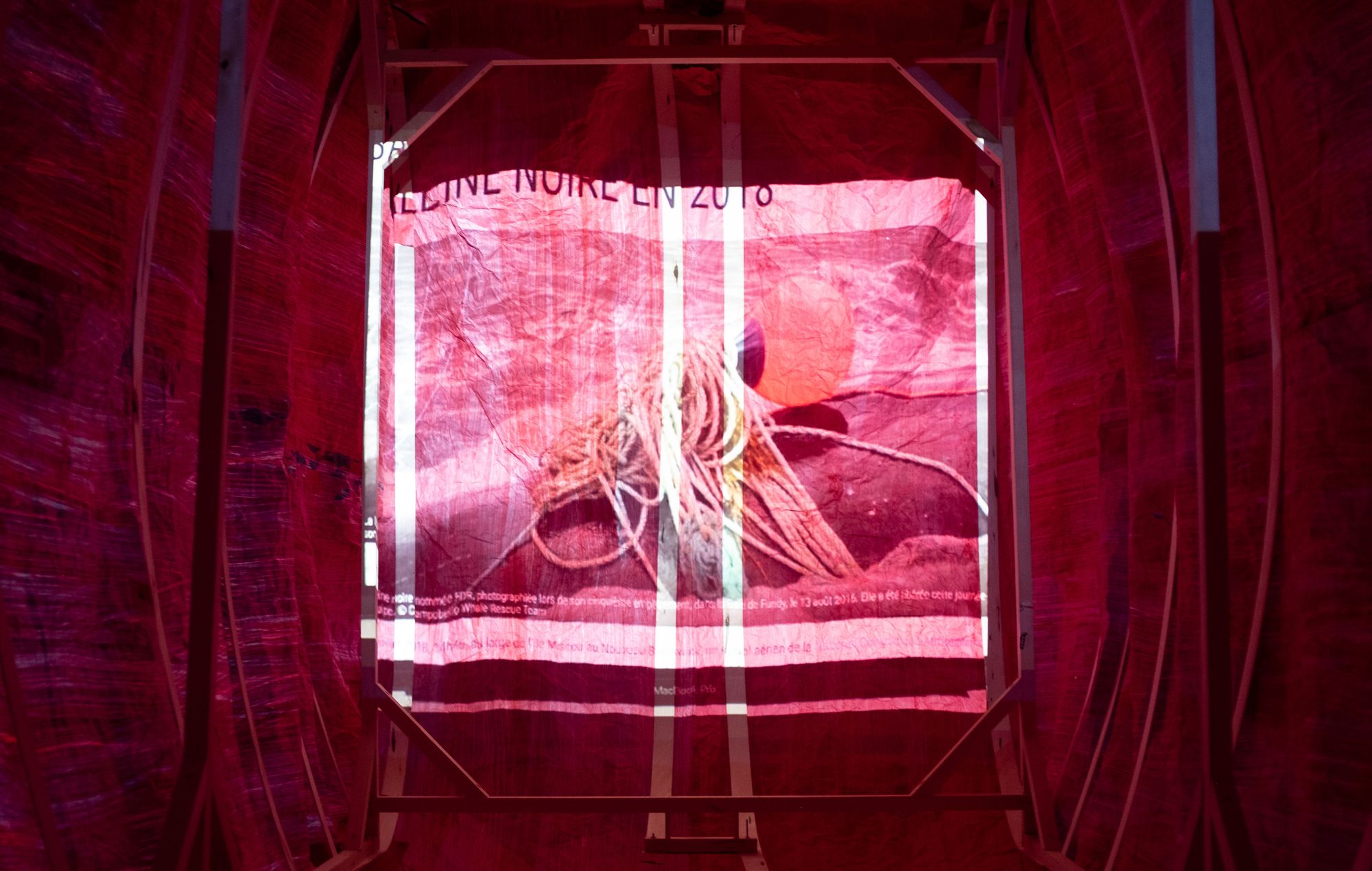

Still in Bonavista, we’re talking to one of the local hosts overseeing Cynthia Renard’s A Sperm Whale Called Tryphon. This is one of the most playful installations in the biennale—a delightful collaboration with school students from across the peninsula exploring the question of what it is for a whale to die, featuring a large paper sculpture of a whale that hangs from the ceiling. There’s a video playing inside of the whale that collages together news items about the whale Tryphon who died, in 2009, while swimming up the St. Lawrence after getting tangled in fishing gear. The kids even wrote letters to the whale.

When we tell another couple there that they should go see Gauthier’s skull at the old hardware store, the on-site host pipes up, excited to tell us a story. There’s a certain way a Newfoundlander’s body starts to shift with excitement when they have a yarn to tell. Apparently, she and her husband were the ones that drove the whale skull from hundreds of kilometers away in the town of Dildo, where for decades it sat outside a small museum. The Biennale had been working with Gauthier to find something to carve. When they stopped to take a closer look at the skull, at first it seemed that little was left of it. Then they turned the skull onto its side, to discover that the surface closest to the ground was perfectly preserved. Ready to be worked. So they loaded it onto the truck, and brought it to Durdle’s.

“Oh my Jesus,” she says, “look at what that artist made from that.”

Or, look at what he found.

Durdle's Hardware Store, Bonavista.

The fourth edition of the Bonavista Biennale ran from August 19 to September 17.