An Inconvenient Place

Despite the deliberate erasures of Soviet historiography, the site of the massacres at Babyn Yar reveals a story spanning several eras of Ukrainian history—though mostly by examining how that story was allowed to be told.

In support of Holocaust Education Week, on November 5, 2023, Koffler Arts organized the half-day symposium “Babyn Yar, the Holocaust and Beyond: Architectures of Memory”, which invited a range of speakers to expand on themes explored by the exhibition, “The Synagogue at Babyn Yar”, now showing at the Koffler Gallery.

Anna Medvedovska is a senior research associate at “Tkuma” Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies, and managing editor of the journal Holocaust Studies: A Ukrainian Focus. She is also a visiting research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin. As part of the symposium, Medvedovska spoke about Babyn Yar’s potential as a symbolic space, while exploring how that symbolism has been transformed over eight decades, from World War II to the Russian-Ukrainian War.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

*

Most people around the world know Babyn Yar as one of the most notorious Holocaust sites, but it is also the one with the most complicated and multi-layered history, and that is what makes it difficult to perceive and memorialize.

On the other hand, by embracing all these layers of history we can get a multidimensional and quite insightful perspective on several periods at once—Stalinist, late Soviet, and post-Soviet. And we can see that Babyn Yar is not only a space of many tragedies, it is also a space of struggle between different narratives—which is still going on till now.

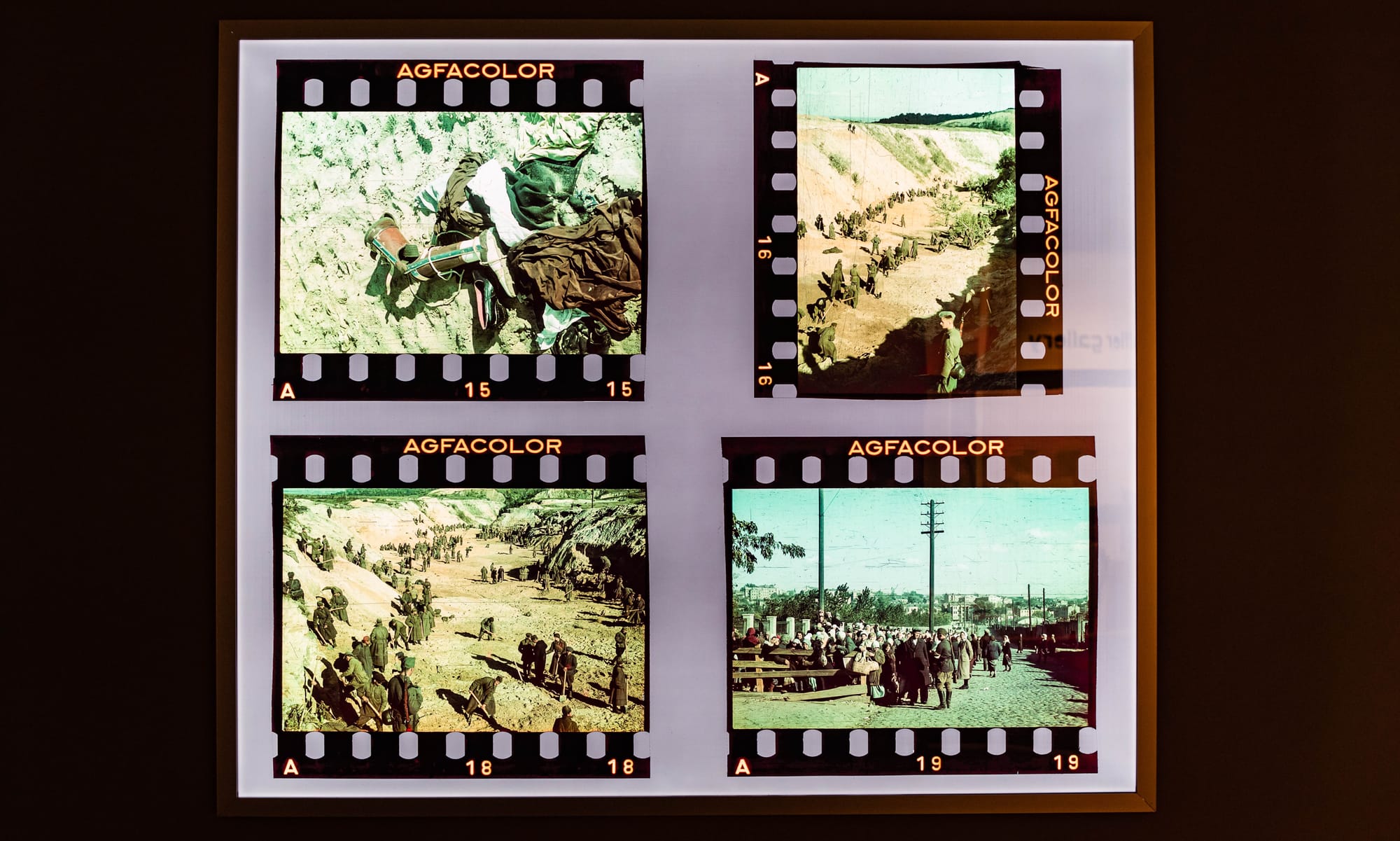

During the German occupation of Kyiv, Babyn Yar was a permanent site where the shootings of Soviet people were carried out. Jews, Roma, prisoners of war, Red Army fighters and commanders, communists, Komsomol members, Soviet patriots, Ukrainian soccer team players, mentally ill people, Ukrainian nationalists (in particular, the intelligentsia), and other categories of victims were executed there by Nazis. Subsequently, Stalinist propaganda and the Soviet nationality policy were increasingly characterized by the practice of dispensing limited amounts of information, or blatantly concealing official data on the anti-Jewish nature of Nazi crimes.

This silencing of Jewishness was undertaken by the Soviet government beginning in 1942—so already in the first year of the German-Soviet war. Toward the end of the war, all mentions of Jews in the context of Nazi victims practically disappeared from Soviet newspapers, from Soviet public space, and were supplanted by the faceless euphemism, “peaceful Soviet citizens.”

For decades following the war, none of the killing sites were marked as places of Jewish extermination. A group of Soviet-Jewish writers, including Vasily Grossman, Margarita Aliger, and Ilya Ehrenburg, assembled a compendium of testimony and documents entitled The Black Book of Soviet Jewry, but censors banned its publication just as it was ready for release in 1947. The chapter about Ukraine was especially criticized, as well as mentions of the collaboration by locals in the Holocaust. Thus, until the end of the Soviet era, the book remained unavailable for a Soviet audience. The general point of Soviet historiography was that the Nazis had targeted all Soviet citizens equally.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of the Ukrainian population, which had itself experienced great tribulation and suffered many losses, was not prepared either to understand or feel specifically Jewish pain. After three years of Nazi propaganda under the occupation, after the practices of the totalitarian ’30s in the USSR—such as collectivization, the genocidal famine of 1932/33, mass deportations, the Great Terror—Ukrainians, the same as the rest of Soviet citizens, did not perceive the Holocaust as something outrageous, as something impossible. The policy of fear and terror was well known to them from the previous decade, from their Soviet experience. Neither did the Soviet practice of concealing the Jewish tragedy elicit any astonishment.

In the minds of average Ukrainians, this governmental policy fully conformed with the Soviet policy of concealing and denying the famine in Ukraine that took millions of lives in the early ’30s. Moreover, details pertaining to the destruction not only of Jews at Babyn Yar, but also prisoners of other nationalities, such as non-Jewish Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, and others, which were made public after Kyiv was liberated, formed such a perception that Babyn Yar was really a place of many tragedies, it was a common grave. In this context, the desperate appeals of Jews to understand the unprecedented nature of the Nazi crimes against them were often perceived by others as Jews’ own inability and reluctance to feel the pain of others.

Public expressions by Jews of their personal attitude to the Babyn Yar tragedy were often treated as attempts at fomenting Jewish nationalism. This was demonstrated by an episode involving a performance by Nechama Lifshitz. Lifshitz was a Soviet Yiddish-speaking singer. In the late 1950s, at one of her concerts in Kyiv, she decided to perform a lullaby to Babyn Yar in Yiddish. As her audience was mainly Jewish they could easily understand the language. The Jewish audience was so shocked, touched, and impressed that Lifshitz had referenced Babyn Yar directly, when everybody had been silent about it for quite a long time.

The audience stood in silent solidarity. Of course, it was immediately noticed and reported to the authorities. After this, Lifshitz was summoned before the party central committee and banned from giving concerts for a year. Later she would emigrate from the Soviet Union.

Throughout the 1950s, under the guise of planning new transportation routes and constructing residential areas in Kyiv, active measures were adopted with the goal of physically liquidating Babyn Yar, which was viewed as an inconvenient place. For this purpose, a pulp consisting of sandy clay was pumped intensively into the ravine.

In October 1959, Viktor Nekrasov, a Kyiv writer and war veteran who fought at Stalingrad, published an article entitled “Why Was This Not Done?” in a popular Moscow periodical. Hoping to use some of his moral authority as a veteran and prominent writer, Nekrasov demanded an end to the abuse of the memory of those who had perished at Babyn Yar and called for their proper commemoration. “Who could have come up with the idea to fill the ravine, or play soccer on the site of the greatest tragedy,” he asked in his article. Such appeals, however, didn’t bring any results. As in previous years, the work of dumping fill into Babyn Yar continued, without adhering to crucial technical requirements.

This led to another tragedy on March 13, 1961, when a dam burst. The ensuing mudslide flooded part of the Kurenivka district, killing hundreds of people, while also turning up the bodies and bones of those who had been shot by the Nazis, as no large excavation or exhumation of human remains at Babyn Yar was ever undertaken.

Even after the Kurenivka tragedy, the Soviet authorities still refused to abandon the idea of redeveloping the Babyn Yar area. In 1962, it was decided to liquidate the cemeteries located along Melnykova street and build a sports complex. Thus, the Soviet government tried its best to deprive Babyn Yar of its original symbolic meaning, by superimposing various functional layers on the site.

Besides Nikrasov, other writers addressed the theme of Babyn Yar directly during the brief period of tentative liberalization known as “The Thaw”. In 1961, Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote a poem that began “No monument stands over Babi Yar…” The author immediately became famous in the West, where the oblivion of the Holocaust site was perceived as one of the signs of Soviet state antisemitism. In 1966, a censored version of Anatoly Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar: A Documentary In the Form of a Novel was serialized in the journal Youth. After Kuznetsov defected to the west a few years later, all his books were made unavailable to Soviet readers.

Meanwhile, Babyn Yar was becoming a focal point for Jewish and non-Jewish activism. Beginning in September 1966, people would gather to mark the anniversary of the massacre. From the late 1960s to the mid-’80s at least nine of the commemoration’s organizers were arrested and given jail terms of a year or longer. Non-Jewish intelligentsia were also repressed and persecuted for taking part in those illegal gatherings at Babyn Yar.

This lack of official memorization becomes, to some extent, an international scandal that harms the image of the USSR. Finally, in November 1966, the Soviet state erected a plaque on the site, which said that a monument will be constructed here, in the future, dedicated to the Soviet people who fell victim to fascist crimes committed during the temporary occupation of Kyiv.

Thus, confronting the discourse of Jewish activists, Soviet officials promoted their own discourse. Ten years later, the monument finally appeared. It was a mass of tangled bodies in struggle, forming a sort of pyramid. The inscription at its base said, “Here, in 1941-43, German fascist occupiers executed more than 100,000 citizens of Kyiv and prisoners of war.” The Jewish identity of most of the civilian victims remained, of course, hidden, but at least some tension was relieved by the monument.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Babyn Yar got a second monument, and its first with any explicit reference to Jews. More than two dozen more markers followed in the next decades, honoring, among others, Ukrainian nationalists, Jewish resistance fighters, Roma people, several Ukrainian soccer players who had been gunned down at Babyn Yar after their team defeated a German team.

After Ukraine’s declaration of independence, Ukrainian society was tasked with rethinking its identity, history, values, and civilizational orientation. The development and promotion of one's own vision of history, which primarily included the titular nation, gained momentum. The tradition of monoethnic perception of the Ukrainian past had strong Soviet roots. As historian Serhy Yekelchyk explains in his monograph, Stalin’s Empire of Memory, under the condition of centralized management, the authorities were interested in instilling in the controlled territories a stable, homogeneous identity, in this way more clearly delineating the space they managed. In addition to this Soviet tradition, Ukrainians’ own victimhood, the tragedies and concealed pages of their history, attracted increasing attention after being silenced for many decades. Among these most topical points in Ukrainian history, we can identify the Holodomor, the anti-Soviet resistance, whether armed or intellectual dissidents, and the struggle for Ukrainian statehood.

It was quite predictable that the basis of the new pantheon of historical personalities would be those who were involved in the national liberation struggle of the Ukrainian people for centuries. Among them, personalities such as Bohdan Khmelnytsy, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, Symon Petliura, Stepan Bandera, and Roman Shukhevych.

The last two figures are of particular importance in the context of Holocaust discussions in post-Soviet Ukraine. This is connected with the political decision made by the authorities to award Shukhevych and Bandera, respectively in 2007 and 2010, the title of Hero of Ukraine, as part of a broad political campaign of rehabilitation and heroization, a glorification of the Ukrainian nationalist movement. The awarding of Hero of Ukraine sparked hot public debates in the pages of prominent Ukrainian periodicals, and to some extent actualized the issue of the Ukrainian nationalist involvement in the extermination of the Jews.

The main problem is that, reflecting the full history of Babyn Yar, one should deal somehow with the contradictory discourses. This is now a part of many broader, ongoing discussions in Ukrainian society—discussions about the role of the Ukrainian nationalist movement in general, and the direct role of Ukrainian police and nationalist militias in particular, in the acts of destruction, their anti-semitic ideology, and, taken together, the complicity of Ukrainians in the Holocaust. Step by step, all these issues have become less shocking for Ukrainians. For example, if we are speaking about the fate of Ukrainian nationalists who were shot in February 1942 at Babyn Yar, we must confess that among them were a number of Ukrainian activists who for a time held positions in the Nazi administration, or were on the editorial board of the occupation newspaper that published antisemitic materials. Which raises the question of how we should commemorate them: as heroes in this glorifying discourse or as Nazi collaborators. If we tell the whole story, it doesn’t fit into a heroic discourse.

At the same time, although their moral position was often far from impeccable, it doesn’t negate the fact of their sacrifice, the fact that they were killed for their politics. But that’s an open question. Now the broad context is related to attitudes toward the Soviet past. The second largest category of victims at Babyn Yar were soldiers and officers of the Soviet Army, communist activists, among whom there were many opinions, but also people of different nationalities, including Russians. How we should commemorate them, especially in the light of the attitude of the mass of Ukrainian society to the Soviet past, and Soviet narratives that exaggerated enormously the Ukrainian liberation movement’s associations and Nazism.

While all these issues remain properly unresolved in Ukrainian society, it is very difficult to develop a concept that would harmonize the memory of such different and sometimes antagonistic victims. In order to reach a consensus, a deep and unbiased reassessment of global issues in Ukrainian history of the 20th century is needed. First of all, to create a general inclusive narrative. There have been plenty of attempts to organize the memorial space in Babyn Yar, from Jewish-Ukrainian, Ukrainian, and Russian initiatives. But they all, in my opinion, were often guided by false priorities. The primary goal shouldn’t be to please Western public opinion. It shouldn’t be to meet the expectations of Western partners and the standards of cultural memory in Europe. And definitely not to impress the world community with the grandeur of the project.

After all, memorial objects are needed primarily to symbolize society’s attitude to history. Of course, if sponsors have a lot of money and want to invest $100 million, we could build 10 big museums, bigger than Holocaust Memorial Museum and comparable with Yad Vashem. But that doesn’t create an inclusive narrative. Mostly intellectual efforts are needed for this, it's a very long process and complicated process, and it requires an intellectual effort by a significant part of Ukrainian society.

The issues of Babyn Yar are potentially much broader than the issues of the Holocaust, and the issues of Nazism. I don’t know if its symbolic potential will ever be realized or not. It can be only realized when this inclusive, historical narrative is written and becomes the mainstream consensus for the majority of Ukrainians. Not necessarily a narrative as a rigid structure, but as an open structure involving multiple perspectives, multiple contexts, and multiple explanations, and entanglements of Ukrainian history.