Beyond the Landfill of Images

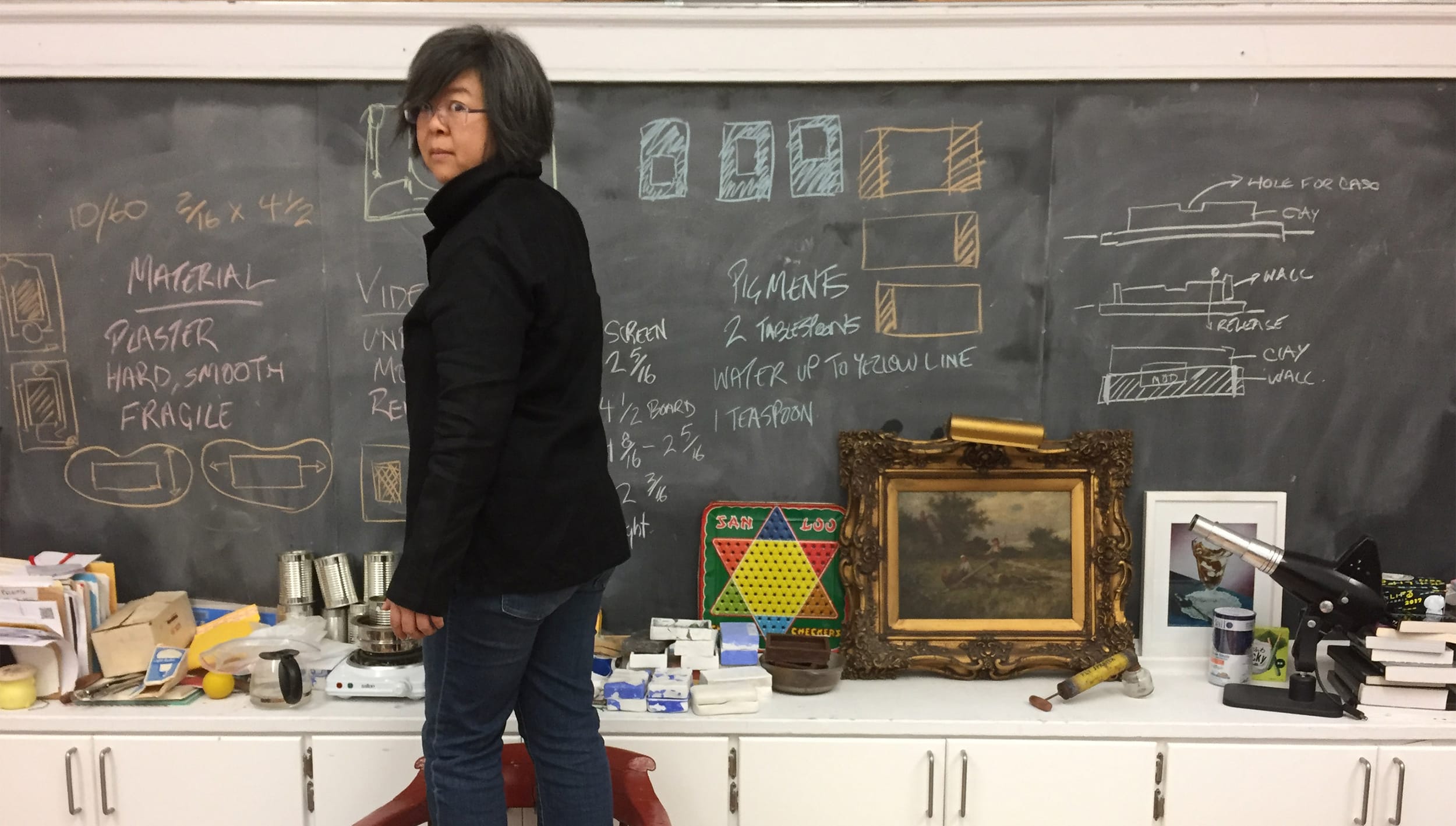

Experimental filmmaker Midi Onodera talks with Arcade about her early adoption and explorations of new technologies, how art making in Toronto has changed, and what the glut of media images might be doing to us.

Midi Onodera has long been at the forefront of experimental filmmaking in Canada, with her earliest works, in the 1980s, screening at Toronto’s The Tunnel, a dedicated experimental film and video space above which Joyce Weiland had her studio. Back then the rent was still cheap and it was possible to make work with few commercial or money-making prospects. With time Onodera has lost none of her intellectual restlessness, or her hunger to experiment with the latest visual and information technologies. In 2018 she was a recipient of a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts; the GG citation, harkening back to her earliest efforts, called her “a thoughtful, daring filmmaker at a time when there was very little diversity in Canadian art.”

Soliloquy Soliloquy, a new Onodera creation now screening at Koffler’s DECADE exhibition, captures the early evolution of today’s artificial intelligence over the span of a 20-minute video. It begins with rudimentary text-based interactions with a chatbot; soon the chatbot has become sophisticated enough to talk on the phone. Onodera has an ongoing conversation with the bot, which she’s named FauxMidi. Are they both Midi? In what way does the technology itself become a collaborator? The AI version of Midi turns out to be stubborn, funny, unhelpful, curt, and occasionally insightful—although that appears to happen accidentally. In reply to the prompt, “Hmm. How about this, what is the % of 59/100?”, FauxMidi says, “Apparently 10% of people can’t identify and describe their own emotions. I can relate.”

The film has an inscrutable, Dadaist quality—the AI answers in obscure and confusing ways, making the follow-up questions equally surreal. The effect is exactly as it probably should be when talking with a robot: uncanny and awkward.

*

I’ve been speaking with other artists featured in DECADE about the nature of their studio practice. What does it mean to have a studio practice as a video artist, what does that look like?

That’s a complicated question. You have to look at video and film within the context of the larger art community. I’ve been practising for so long, and I come from an experimental film background, which was very separate from video back in the day. We’ve always had a precarious position with the rest of the art world. Just because of the nature of film and video, it’s time-based work, it requires equipment, it’s not like a painting where you just put it on the wall and can stand back. It’s something that demands time from an audience. It’s different when you create works for a gallery, as opposed to creating works for a theatre situation. So I think that my work straddles both worlds in a way. To have a studio practice is the same as any other artist, it’s a space where you come and you are free to imagine what will happen.

You note the context of the video being shown—at a theatre versus a gallery, or on your phone—is important. How do those differences impact the work? For the video piece that’s part of DECADE, could that only be shown in a gallery setting?

The one up now at Koffler, Soliloquy Soliloquy, was originally designed for mobile devices or online viewing—originally the series was just called Soliloquy. It was a conversation with myself and phone Midi, an AI creation that I made through this app. It was a year-long project. Then I was invited to a show for Critical Distance, but this was right before the pandemic and it fell through. Originally I was going to project the Soliloquy videos somewhere unexpected, like on a fuse box, for example. I really liked the notion of stumbling upon something and seeing it.

The videos in Soliloquy Soliloquy have the sense of being security camera footage. Where does the footage actually come from?

The original footage was time-lapse footage in different locations. I found different locations and set my camera up for 24 to 48 hours, and then cut it together.

I’m interested in the aspect of your work that uses AI or chatbots, and the relationship between the real and the fake. I listened to a recent clip of you speaking and you talked about how we now consume so much media that we don’t question the images we see. But then we saw what happened with Kate Middleton touching up her image, is there maybe a switch happening in our becoming more skeptical of images? What are you thinking about in terms of reality and fakes in image making?

That’s a really huge question. I think that every artist who creates images in a moving-image capacity has to be thinking about that, if not consciously then unconsciously, because you’re right we consume so many images. And what does that mean? What does it mean when we consume images? What does it mean for our brain? What does it mean for our psyche or relationship with other people? It’s so complicated. As a person who makes images, I’m very aware of that. I think of images like it’s a big landfill. We’ve got all these massive, invisible landfills of images, moving images. What do we do with all that? Do we recycle it? Do we just bury it in the ground and leave it there? What do we do? My practice has really gotten into using a lot of film footage, reusing that footage, because I kind of feel guilty creating new ones. If I create a new image, it has to be really significant, I have to really think about it and consider it, because I don’t want to just keep throwing stuff out there. I don’t want to just keep adding to the landfill.

I watched one of your YouTube videos, called Is anybody watching? It seems like a big part of the project is the loneliness of that landfill. People are projecting images at nobody.

That was a really interesting project. You can’t do it so much on YouTube anymore, because they changed the algorithm, but at the time what you could do is type some nonsense into the search bar and up would come a bunch of videos with that label because a lot of people don’t re-label their files when they upload them. So the name is the name of the original digital file, which would be something like “xyz0123”. Then up comes this video and it has one view. It makes me think, how did that happen? Why did that person upload it? Why did they not even think about renaming the file? Did they not know how to do it or what? So I started looking for videos with less than ten views. When I found something, I would try to connect with the person who made it. I was not successful in connecting with anyone, but I would take their footage and then remake it into something and use it that way.

Do you think that as humans we have an inherent desire to make images of ourselves?

Oh, for sure. It’s like a reflection in the mirror.

When you started making films you were using Super-8. Which was very tactile, you were cutting your own film, or adding your own subtitles. Do you still use Super-8?

Yes, I made a short film a few years ago and it was looking back at the same locations in Toronto that I had shot in the ’80s. I made this film called Ville-quelle ville?. It was mostly shot in the east end of Toronto. And it was from the perspective of a young woman wandering around in the city. Then I thought, I really would like to revisit those places and see if they even exist anymore. I decided to make a film, based on the same shots, the same locations, everything as much as I could remember and figure out and reshoot from the perspective of an older woman. Those are kind of companion pieces that are like 30 or 35 years apart.

What was it like to make art in Toronto at that time, compared with now?

It was so different back then, the city was different. It was smaller. It was much cheaper to live. You could have artists who had a part-time job, but they were able to live fairly cheaply, maybe with a bunch of people or maybe in a very small place, and do their work. It was feasible. And no one thought about the future. No one was like, I’m in my 20s I better start saving for my retirement.

There were people around that you could rely on, that you could source, that you could ask questions about things that you didn’t know. It was a community, as much as the experimental film community was separate from the art world or the art community in the west end. Everyone still knew each other. Today, I think that it’s shifted because of the expense of living in the city. So many artists are moving out. It’s almost impossible to have studio space. How can you have a studio when you can barely afford your rent? Are you working maybe two or three jobs? How do you have time to do your art? How do you have time to go to the opening? How do you have time to go to a show? It’s a very different climate now.

Does that make it hard to be experimental? If you’re going to spend time making art, does it mean playing it a bit safer?

You may have to think about what’s my return on investment? How can I sell this? How can I make some money to support myself? The thing about experimental film and video is that it’s never been about making money. You’re never going to have a blockbuster Hollywood hit from an experimental short, it’s not possible. There was never that kind of capitalist connection. With painting and photography, those are objects. Objects can be sold.

How do people make money on experimental films?

It’s hard. The bottom line is you have to be really passionate about what you’re doing. I think that for younger artists, it’s really hard. To have that space of being able to look at work in a different way that’s non-commercial, I don’t even know if it’s in the cards anymore, because you do need to survive. At a certain point when you’re young, you can start and get by, as I definitely did. But when you get older, it also becomes harder, you’ve got different obligations and responsibilities.

You’re doing a project using AI on social media right now called Project Pizzini, and you’re uploading a video every month. How did that project come to be?

A pizzini is a small note. Originally, it referred to these notes that were left by mafia members in Italy. They would write little notes and then leave them in, like, pieces of furniture, somewhere hidden. Then the next person would come along and find those notes. That was the original idea. I love that notion of hidden notes being found somehow.

I’m working with the poet Ronna Bloom. She creates a note that supposedly has been found somewhere and takes a photograph of where that note has been found. Then I make a video based on the note. The following month I will use a free online AI text-to-video program to make another video based on the same note. Text-to-image AI programs are very common now, but text-to-video is just starting. Of course, that interests me as a moving image artist. So I enter what I think best describes the video I made and see what the program spits out.

Have you been surprised with the results?

For the first video I was shocked. I was like, where did this even come from? It was all about sports and I didn’t even enter sports into the equation. For the second video, coming this month, I found a program that’s supposed to be the most cutting-edge text-to-video tool. The result is even weirder than last month.

Why is it important for you to continue using all of the newest technology?

I think it’s really important that we look deeper into what’s happening. Without that kind of curiosity and exploration, we’re just walking into a void or a black hole. Unless we can really start to question and consider what’s being done, we will be lost.