Coming Home to Beauty

Marcel Dzama’s show at the McMichael is an ecstatic awakening of the wild things that stalk the inside-out Canadian landscape.

When painting the evening,

While the world is unease,

The young northern painter,

Painter of trees.

Your evening has ended,

The moon is out low.

Hit your head upon it,

And sleep in the waters below.

That pale horse rider,

Has come here so soon.

When there’s war on the earth,

And blood on the moon.

— Tom’s Blood Moon, Marcel Dzama

In the catalogue accompanying Marcel Dzama’s first Canadian exhibition in more than a decade, McMichael chief curator Sarah Milroy shares that her initial idea had been for Dzama to explore something political—an exploration of ideas around authoritarianism, anarchism, revolution, and resistance that have long drifted through his work, alongside all the weird creatures, dancers, and Picabian-polka-dotted dancers he’s best known for. After thinking on it for a while, Dzama replied, “Actually, I really want to think about Canadian landscape and Canadian landscape painting.” As though there was a difference.

Since his childhood in Winnipeg, where he put on puppet shows and charged the neighbourhood kids for admission, and then his co-founding of The Royal Art Lodge with fellow art students at the University of Manitoba, Dzama’s work has been part-rebellion, part-carnival, mashing up the punk aesthetics of longtime collaborator and sometimes mentor Raymond Pettibon with the provocations of Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp, and then fermented in Maurice Sendak’s wild imagination.

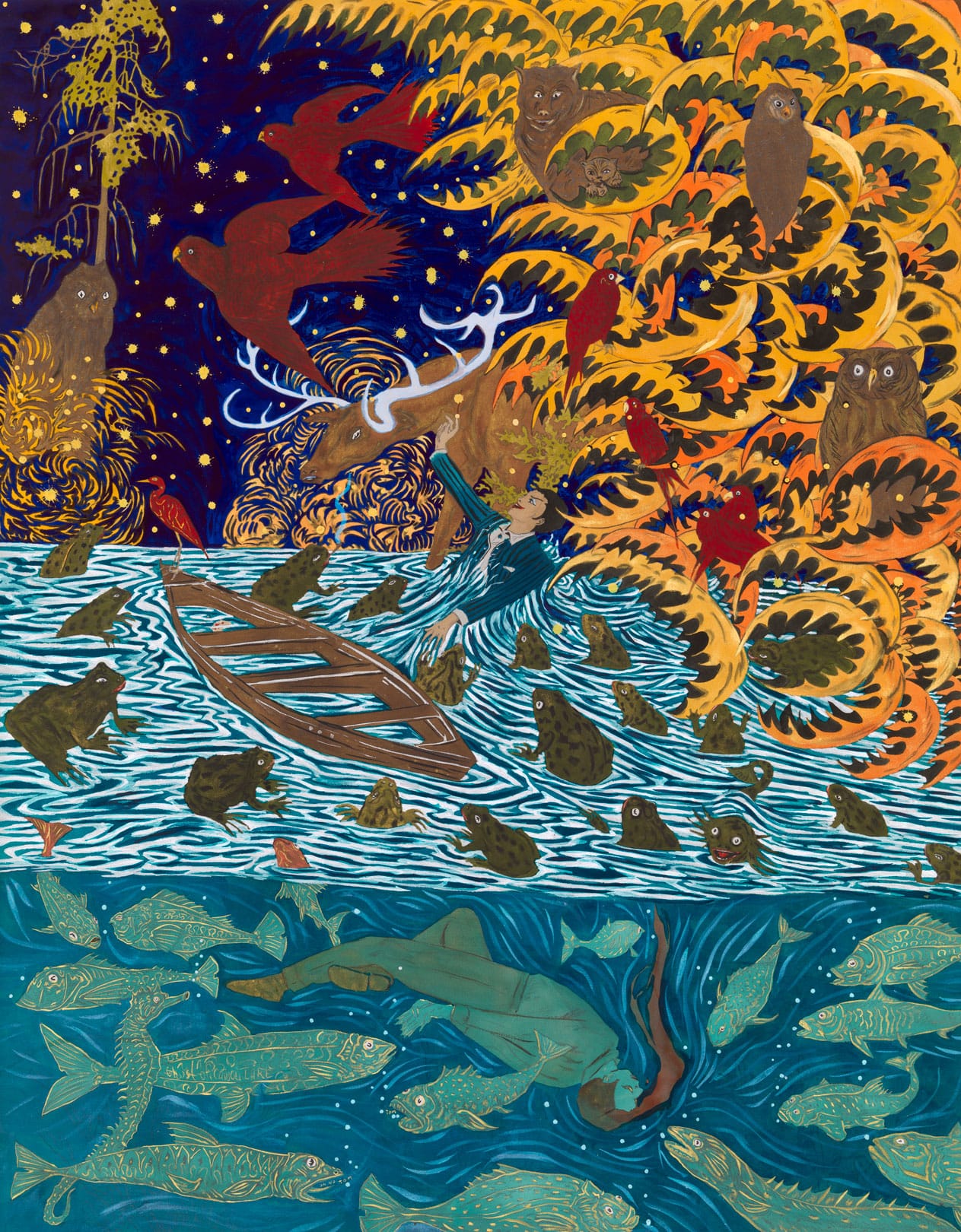

The “thinking” Dzama wanted to do resulted in the frenzy that is Ghosts of Canoe Lake at the McMichael, a voluminous outpouring of new works at all scales, centered around that most iconic and foundational of mysteries in Canada’s idea of its art self—the night Tom Thomson slid into the watery darkness of Algonquin.

There are two ways into the physical space of the exhibit. The first and most obvious, at least when I saw it, was via one of the more voluminous showings I have seen of Thomson’s work, which placed some of his more familiar and influential works, such as The Jack Pine, alongside a large number of his lesser known en plein air oil sketches. The other way in was past a much more modest but equally fascinating exhibition (still on through April 21) about the mining town of Cobalt, which documents the efforts of between-war painters and photographers such as Isabel McLaughlin, Bess Harris, and Franklin Carmichael to understand the newly transformative nature of resource extraction as inherent to our relationship to land. From whichever direction you arrive at Ghosts, our ideas of the Canadian landscape are in flux—with Dzama ready to set off a few firecrackers.

Left: Marcel Dzama in his Brooklyn studio, 2021. (Photo: Jason Schmidt, courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.) Right: After the Fire, Before the Flood (detail), 2023, pearlescent acrylic, ink, watercolour, and graphite on paper, 28.3 x 43.2 cm. (Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner © Marcel Dzama.)

Is it too obvious to say that the best way to understand your own idea of Canada, is to figure how you make sense of the land? After living most of my life on other continents, I returned to Canada a decade ago. When it came to figuring out what shape this new life should take, I did it by getting out on the land, with mud on my boots and paddles in water, lifting up rocks to see what was underneath. It’s been a decade also marked with too much personal trauma and grief. Coming back to the land, whenever possible, has always felt like a reliable way of returning, not to peace as such, but to a deeper, wilder place from which to approach understanding.

Dzama’s work has evolved since his last exhibition in Canada almost a decade ago—work that I had tended to file somewhere comfortably under that sort of Spike Jonze/David Eggers umbrella through which he partly came to broader attention. His usual motifs are now set against a lusher backdrop. In these paintings, nature is ecstatic and horrific in equal measure. It’s an electrification of territory in collapse, shimmering with an intricate, pearlescent depth that loses much in the translation to page or screen. Gamblers, spirits, and drifters lounge in a landscape that’s died in fire and ready for rebirth. Creatures stalk the edges and centres of frames, amused by our disorientation. Amidst the ponds and forests of this Dadaist wilderness, cats lounge in ferns and tropical birds perch next to lost pets, children, and grandparents.

In one painting, the masked jazz band “The Duchamps” seem to be bashing out a tune with something like a ragtime energy. But that energy’s not exactly positive—something dark is afoot. The sharp lines of their pinstripe suits are complimented with black armbands, and on the ground, or perhaps the water they’re standing on, a machine gun sits carelessly dropped. In a neighbouring image, The Duchamps are now the backing band for a pig-faced dictator holding a microphone.

But amidst the skulking menace, there’s also hope and light. I didn’t come from your rib . . . you came from my vagina (or, The origin of us all) is an explosion of life from a cosmic vagina, which is flanked by two of Dzama’s suited dancers, their dance fuelling the energy as much as being fuelled by it.

Screening under a tent in the centre of the exhibition is a new film, To Live on the Moon (For Lorca), inspired by Federico García Lorca’s unproduced 1929 screenplay Trip to the Moon. In Tom Thomson and Lorca, Dzama brings together two men who, he says, both “suffered the fatal consequences of their times”, dying from the presence of war, rather than the war itself. Dzama himself plays Thomson, and in a roundabout way that feels indebted to Dalí and Buñuel, we witness Lorca’s murder by Spanish Nationalists, leading to a raucous second-line funeral march that transforms intense joy into an act of resistance.

But it’s in the full-wall triptych painting After the fire before the flood, where Dzama’s thinking—and mine—is really let loose. This is the artist going big, and straight into the delicious dark. In the left panel, beneath a starry night sky, one of his polka-dotted characters stands in water and holds up a drawing of a dove with an olive branch, like they’ve brought it home from school. Alongside, a girl cradles a pig wearing a bonnet. Two cats wade in the water beside them, not at all interested, for some reason, in the flock of red tropical swifts. A third cat, legs akimbo in a palm tree, seems to be considering the birds with stoned satisfaction. Underwater, a flurry of fish and lizards share worried looks at each other. Perhaps they feel a pull in the undercurrents.

In the centre frame, the water appears to pull harder, and the creatures struggle to stay afloat, perching and paddling as best they can. A woman in a domino mask (possibly or not the Lady Luna from other paintings) holds two frustrated cats safely aloft. Lightning crashes the sky and horses buck in terror. There’s a fire just over the horizon.

And to the right, Tom’s sinking canoe. As the water surges around Thomson in his pinstripe suit, he reaches for the antlers of a moose. A phalanx of frogs look on with concern as though willing him upwards into the trees—trees that are either on fire or in deepest fall. Whichever way, the owls up there seem prepared to accept him. Below the water’s surface, the fish now watch in horror, as Thomson in simpler attire sinks, stricken, gone. The ascending spirit is rent from his body. In both directions, all the creatures of the burning night bear witness.

After the fire, before the flood—there’s no simple sense to be found in our landscape. The horrors we’ve buried, both systemic and personal, never sit static. They never fully decompose. With a glorious opportunity to look at the landscape through Dzama’s eyes, I realized a little more of how I look at it myself. It’s not to bury the grief or the darkness, or to consider it all through the lens of the inevitable and ongoing collapse it faces. It’s not to seek relief, or scratch through the dirt for new roots to hold on to. It’s rather to find the sparks of beauty and wonder that point ways forward—none of them simple, none of them without compromise. In the land, all death is rebirth. All ends are beginnings.

In the end so much of Canada’s myth of its artistic self comes back to this lone man setting out into the waters of Canoe Lake—perhaps dodging the war, perhaps murdered. Regardless, never to return. Dzama’s Canoe Lake is a portal to an ecstatic understanding of what’s ahead and behind us. He invites us not just to look, or ponder with solemn gravity, but to throw ourselves into it joyfully and be reborn. To become, as Lorca himself does in Dzama’s film, the moon itself.

“Stopped in My Tracks” is an ongoing series in which an Arcade contributor reflects on their encounter with an artwork that altered their perspective.