Discovering a Room You Didn’t Know Existed

Arcade speaks with Toronto artist Nancy Friedland on what drove her mid-career transition from conceptual photography to painting, and how the anticipation of grief lay at the heart of much of her work.

“Basically, all of this is a bit of a midlife crisis,” says Nancy Friedland, gesturing at the collection of new paintings mounted on the wall of the fourth-floor studio space she shares in downtown Toronto. “I wanted to get back to messing with the surface of the image,” she adds. “I don’t know how or why, but I knew that I needed to get physical with whatever I was going to start making again.”

It’s a bright Sunday morning in June, and later this evening the paintings will be packed up for shipping to her upcoming exhibition in Santa Fe, I Wish I Had A River. But the midlife crisis the 53-year-old artist is referring to has less to do with these new pieces in particular, and more so the decision after her 2016 exhibition Constellations to abandon more than two decades’ worth of conceptually-oriented photographic work and turn to painting—something she hadn’t really done much of since she was a kid.

And yet, the change in direction was also inspired by something far less tangible in its materiality—her attitude toward social media, especially as the mother of three teenagers.

“It had something to do with the embarrassment of being a human with a body—both for them as teenagers and for me at my age—and seeing how they were interacting with social media. They’re all good athletes, they’re always trying something new, and trying not to be embarrassed by failing.”

Friedland explained to them that she was going to take painting lessons with the artist Roberta McNaughton, and didn’t expect to be very good at it. “I told them that I’m going to fail, and I’m going to fail publicly, because I’m going to post about it. In a way I was trying to set an example of how you could be a multidimensional human being on social media, that you could show even the embarrassing parts of yourself and people will still love you.”

Friedland is an old friend from the early 1990s, when we were both undergrads at the University of Toronto, and the only person from those days that I still sometimes bump into while walking around the city’s west end. I caught many of her shows over the years, often at one of the spaces on Queen St. West run by the late gallerist Katharine Mulherin. While I enjoyed the photographic work, I sometimes wondered whether I’d have appreciated it as much if I wasn’t already attuned to Friedland’s dry and somewhat perverse sense of humour.

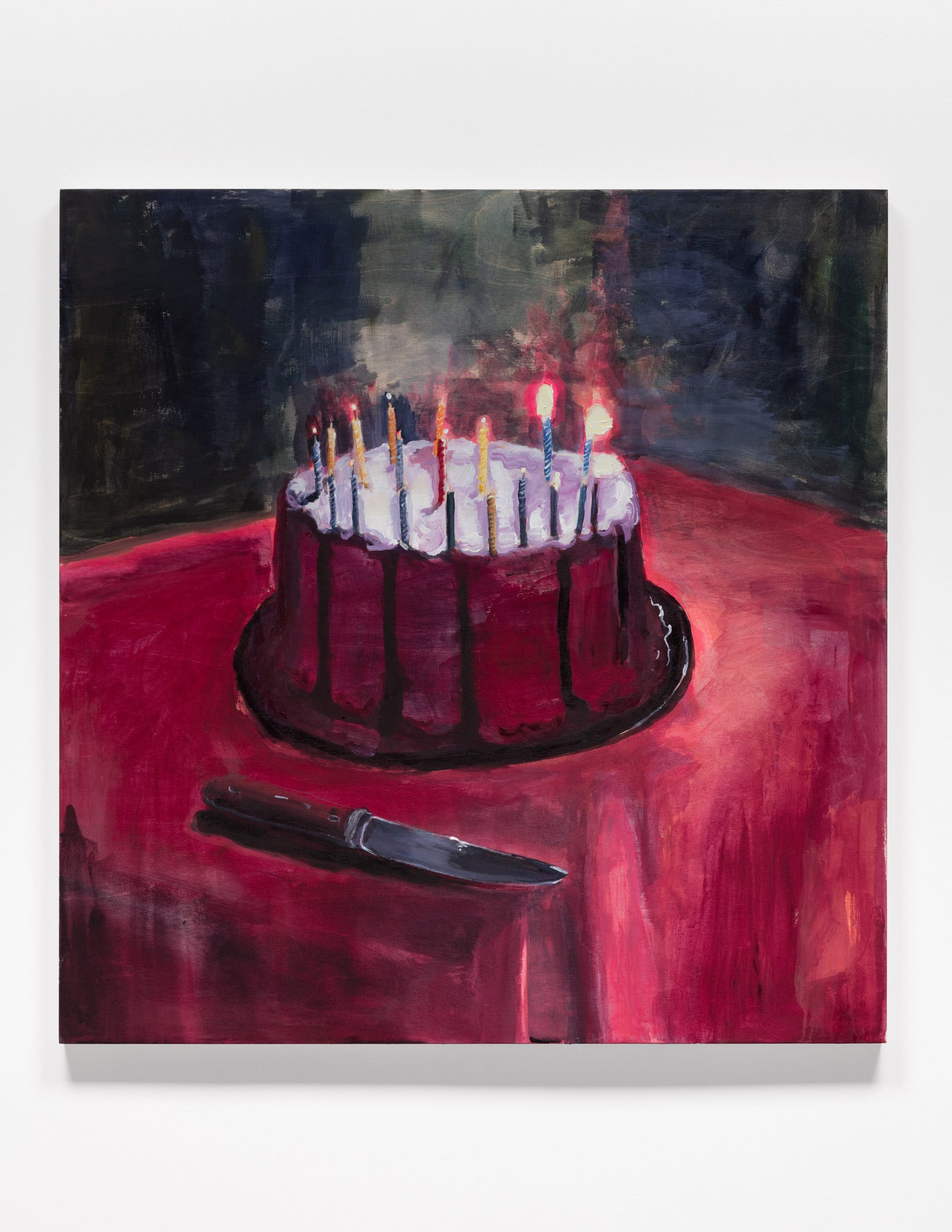

More than five years into her practice as a painter, at first glance Friedland’s work couldn’t be more different in style, interest, or intent, from her earlier photo-conceptualism. “There’s no joke,” she says, “there’s no wink, they’re much more direct.” The subject matter of her paintings certainly appears more immediately evocative and intensely personal, from moments captured of family and friends to pastoral scenes of cottage life, though human figures are often rendered in silhouette, as reflections in water, or merely as a shadow on a wall.

Look closer, however, and the camera lens, or what Friedland calls her “photographer’s brain,” is very much still present. Mainly in the way that her paintings often incorporate the kinds of optical effects one only gets from a camera—a flash-lit forest, the flare of a car’s headlamps at night, and the other lens-like distortions worked into the texture of her paintings.

More than once, I’ve stood looking at one of Friedland’s paintings, and my own brain has wanted to read it as though it’s some kind of photograph, or a simulation of a photograph, in spite of their thick brush work and hazy outlines. As she’s quickly matured as a painter, more through lines from her earlier work have become apparent, whether it’s the ephemerality of both object and image, whatever the medium, or how the pieces feel anchored in an incipient sense of loss, as though trying to reproduce something like very the texture of memory.

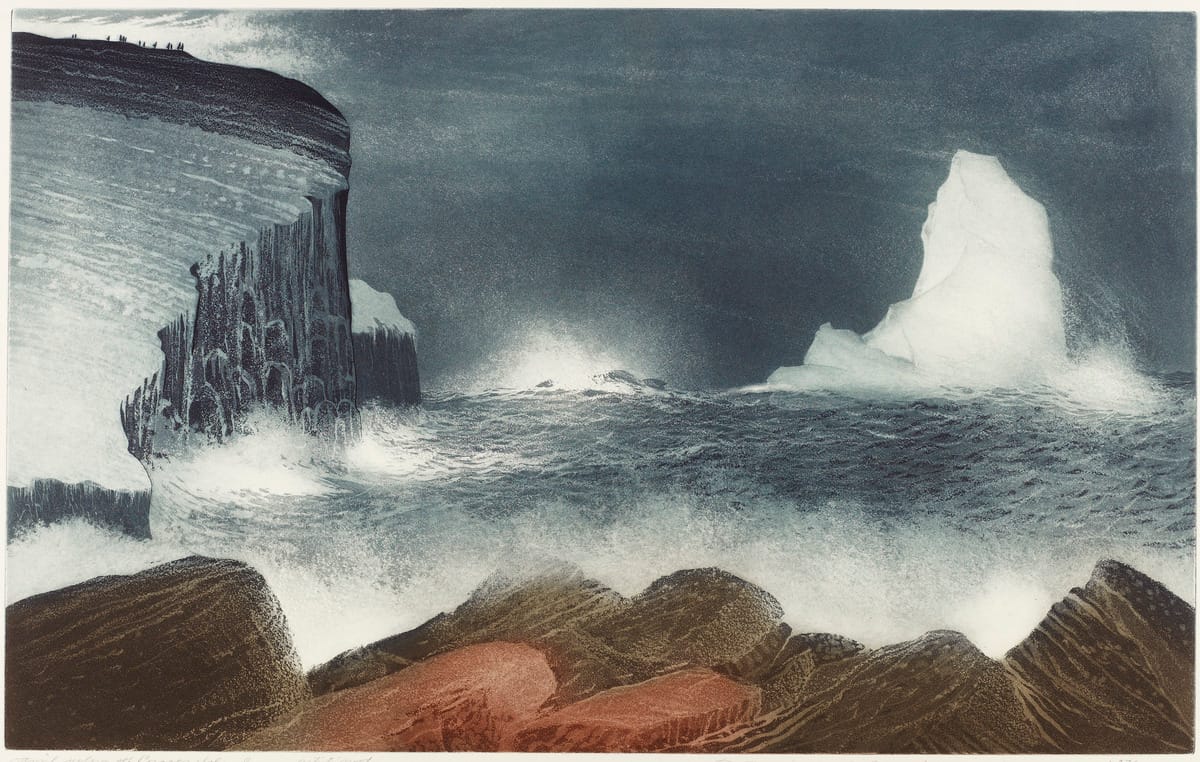

The paintings have earned Friedland a level of recognition and acclaim that she struggled to achieve as a photographer. I Wish I Had a River, which opened at Santa Fe gallery smoke the moon in late June, is already her second collection of new work to show this year, coming on the heels of Heavy Weather, a solo exhibition of 20 new paintings at La Loma Projects in Los Angeles in January. Her paintings have also recently appeared in Harper’s and the New York Review of Books.

“Maybe it was partly because the whole idea of learning was built into the process,” says Friedland, “but I remember saying in another interview how with my first paintings it was like I was a right-handed tennis player who suddenly discovered they’re actually left-handed. Or like discovering that room in your house you didn’t know existed.”

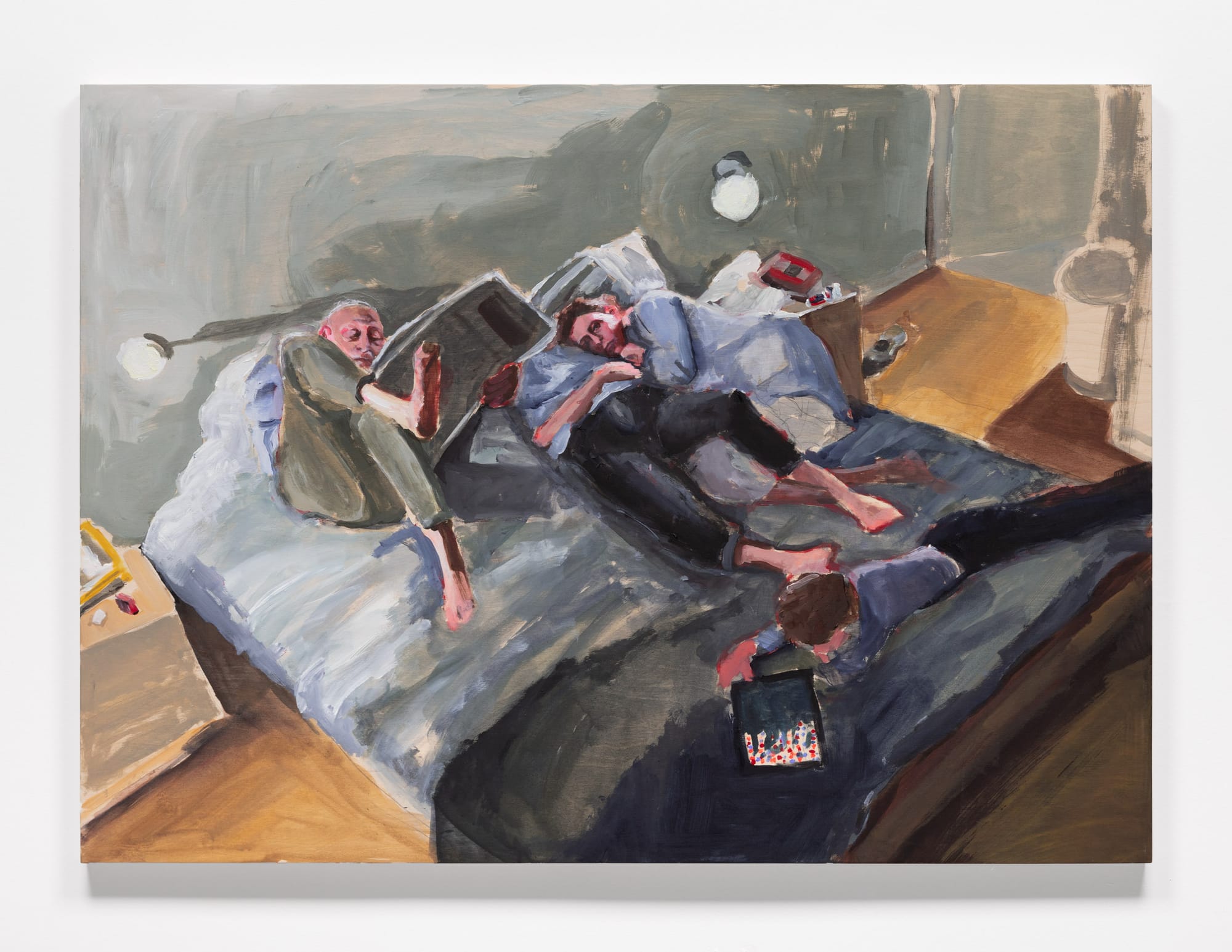

You’ve painted members of your family before, though usually alone, in portraiture. With I Wish I Had a River there’s now this sense of almost domestic or family drama—like they’re all characters interacting in a scene. Where did that shift come from?

The series started with this painting here, around the end of last summer—this is my middle child, who is 17, leaving for his first year at Dalhousie University. [See next image below.] He’s saying goodbye to my very, very old father, and there’s my mom looking on. It was one of the first times that I had painted multiple parts of my family interacting in some sort of dynamic like that. It felt like there was so much coming out emotionally in this particular painting that I put it away for the time being and continued working on the paintings for my Los Angeles show.

When I picked it back up later, it began to feel like a new part of my brain that I haven’t really explored before. Then there’s where I’m at in all of these scenes—definitely from the perspective of me watching all of these characters. I’m the perspective. That’s my photographer’s way of thinking. I don’t always remember that not everyone paints that way. But I’m definitely still using my photographer’s brain.

Your photographer’s brain is also present in the way you incorporate the sort of optical effects one only gets from a camera into the texture of your paintings.

I’ve spent so much time looking at photographs and parsing them out, like “This is a hot colour and this is a cool colour, and this is what happens when they meet, and this line here…” I always think of it sort of as a flat, one-dimensional thing, like I don’t know if I could see it in the real world. I think the image mentally needs to come through that photographic process in order to get to my brain.

And yet, you once said in an interview about your shift to painting that you just couldn’t take a photograph anymore.

It wasn’t so much that I couldn’t take a picture anymore, cause I’m still taking pictures all the time. It was more that I wasn’t interested in the object anymore. I couldn’t make another photograph. Part of it was just the process, which I don’t love. The computer, the printer, the whole disconnect from the part of that process that isn’t hands on. I didn’t want to go back into a dark room. I’m not interested in the gear, none of it. So in terms of just making things, the idea that I could go into my studio and at the end of the day I would have something… I like objects.

During the pandemic, I was so productive making things, making something every day. My mom is an occupational therapist and definitely part of staying well for that time was just making things.

We’re speaking five years after the passing of your good friend and supporter, the gallerist Katharine Mulherin. Among the many things to admire about Katharine was the fact that she never hesitated to show or represent painters, at a time when painting wasn’t considered “cool” or worthy of serious critical attention.

Katharine loomed so large in all of my art thinking. From the day I graduated and had my first show at her Bus Gallery, all the way through my photographic practice. And the obvious place to go when I decided to learn how to paint was Katharine, with some of the painters that I knew through her, like Roberta McNaughton, who I took classes with.

I’m surprised now looking back, how when I was in grad school and everybody was saying painting is dead and I was like… I still don’t even understand why or how anybody makes that statement. If you’ve painted, you know the unique pleasure in it. It’s like saying swimming is dead. Katharine just liked what she liked, she wasn’t out to figure out the next big thing. She was going to blaze her own trail no matter what, and part of that was being true to what she really liked and believed in.

What Katharine represented was no barrier to entry, you didn’t have to have a pedigree, you didn’t have to have a degree. She often showed, in quotes, outsider art. You didn’t need to be part of the moneyed class or speak the language. And she had all these connections to all these people from many different worlds.

The first show of your paintings was at 1086 Gallery, which Katharine was renting at the time. What was her response to the work?

At the time I was trying to make this transition to painting, she was really struggling to make ends meet. She was always hustling, always had multiple projects on the go, and always stealing from Peter to pay Paul, making money over here in order to fund this project over there. I showed her a little bit of what I was working on, but the paintings were priced too low for her to make any money from it. I just wanted to get them out into the world and wasn’t concerned about price. So I rented 1086 from her for ten days. She helped hang the show and came by often to see how it was going.

It was shortly after that when things kinda fell apart. One of the many sorrows of the end of her life was that she was still having to hustle as hard as she was to make ends meet. She probably thought she’d be somewhere further down the road, more established.

Left, Hydrangeas (2024), and at right, Name Your Shadows II (2024), both from the series I Wish I Had a River. (Photos: LF Documentation)

Your mother is 85, and your father is in his early 90s. Your three kids at or nearing the point where they’re leaving home. As much as there are moments of joy and tenderness in the new paintings, there’s also something about them that seems suffused with the anticipation of grief.

Part of my initial interest in photography, which still comes through in basically every painting that I do, comes from this kind of crucial story in my family of my mom’s mom, my grandmother Tillie, who died when my mother was only 10. It’s sad enough to lose a parent, but even sadder to lose a parent when you’re a child. That story is like this touchstone story in our family. There are photographs of Tillie that have always held this incredible kind of sadness and magic. Knowing the story of her death, they’ve always been infused with that anticipatory grief. Because my whole life I’ve known how that story ends. The photographs of Tillie are in that same category as Roman Vishniac’s photographs of the Lodz ghetto before the Holocaust.

Photographs can have this sadness in them, even though they might be, you know, photographs of a happy trip to Florida or some family gathering. It’s just in there and I think that that was the thing that I was so interested in when I went to grad school and studied photography, and it’s carried through in almost all of my work. Like maybe I’ve taken a few detours here and there, but basically that theme of this kind of beautiful loss—I don’t know how to paint without that.