Haunted Landscapes: Days with Ian Strange

While trying to work on a book about illness on a residency near the former POW camp of Stalag-17B, Jonathan Garfinkel is drawn into friendship and dark contemplation with the Australian transdisciplinary artist Ian Strange

I did not go to Krems, Austria to write about dark and hidden histories. In spring 2024, I was midway through a book about chronic illness. The invitation by the Niederösterreich Artist in Residency (AIR NÖ) program, along with Literaturhaus NÖ, was an opportunity to make some headway. For two months, I would have a studio with a small kitchen, bed, and a view of the Danube. There would be artists from other parts of the world in neighbouring studios. Located in the famous Wachau wine region of lower Austria, one hour from Vienna, I anticipated days of writing, strolling along the river, a life through wine-coloured glasses.

But history—Austrian history, particularly for a Jew of Central European descent—has a way of making itself known. In my case, it greeted me at the entrance to the former carpet factory now renovated into a four-storey artist space. Across the street glared an enormous maximum-security jail, Stein Prison, an area of several hundred metres. There were guard towers, lights, security cameras. While being shown around on my first day by Klaus Krobath, AIR’s program manager and project coordinator, he told me that during the Second World War the prison was used by the Nazis to incarcerate political enemies from Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Greece.

On April 7, 1945, with the Soviets encamped outside Vienna, and the fall of the Nazis imminent, the director Franz Kodre released the prisoners. As the newly freed strolled through bucolic fields and sprawling vineyards, thinking of a warm meal and a place to sleep, the townspeople hunted and gunned the prisoners down. Those who weren’t shot fled to the forest. Over 600 were murdered that day and thrown into a mass grave, an incident that became known as Kremsen Hasenjagd, the Krems Hare Hunt. In 2018, an Iranian-born Viennese artist, Ramesch Daha, painted the names of the prison register for 1944 and 1945 and blew them up on the eastern wall in giant blue lettering, several dozen metres high, in commemoration for this stained past.

As Klaus led us past the blurred names of the murdered, we came across some university students strolling to their classes. Then we turned onto the Kunstemeile, an impressive city block of art galleries built by the regional government in the early 2000s to buff up the local culture—an initiative that also gave birth to AIR and Literaturhaus NÖ. I felt the juxtaposition of a disturbing history pushing up against a comfortable, even luxurious present.

While the Danube wound quietly outside my studio’s window, on that first day I wondered if Stein prison was a distraction from my work, or a calling to something I did not wish to know. In time, I got used to Stein prison and its dark legacy. That’s the way things go. We get used to things.

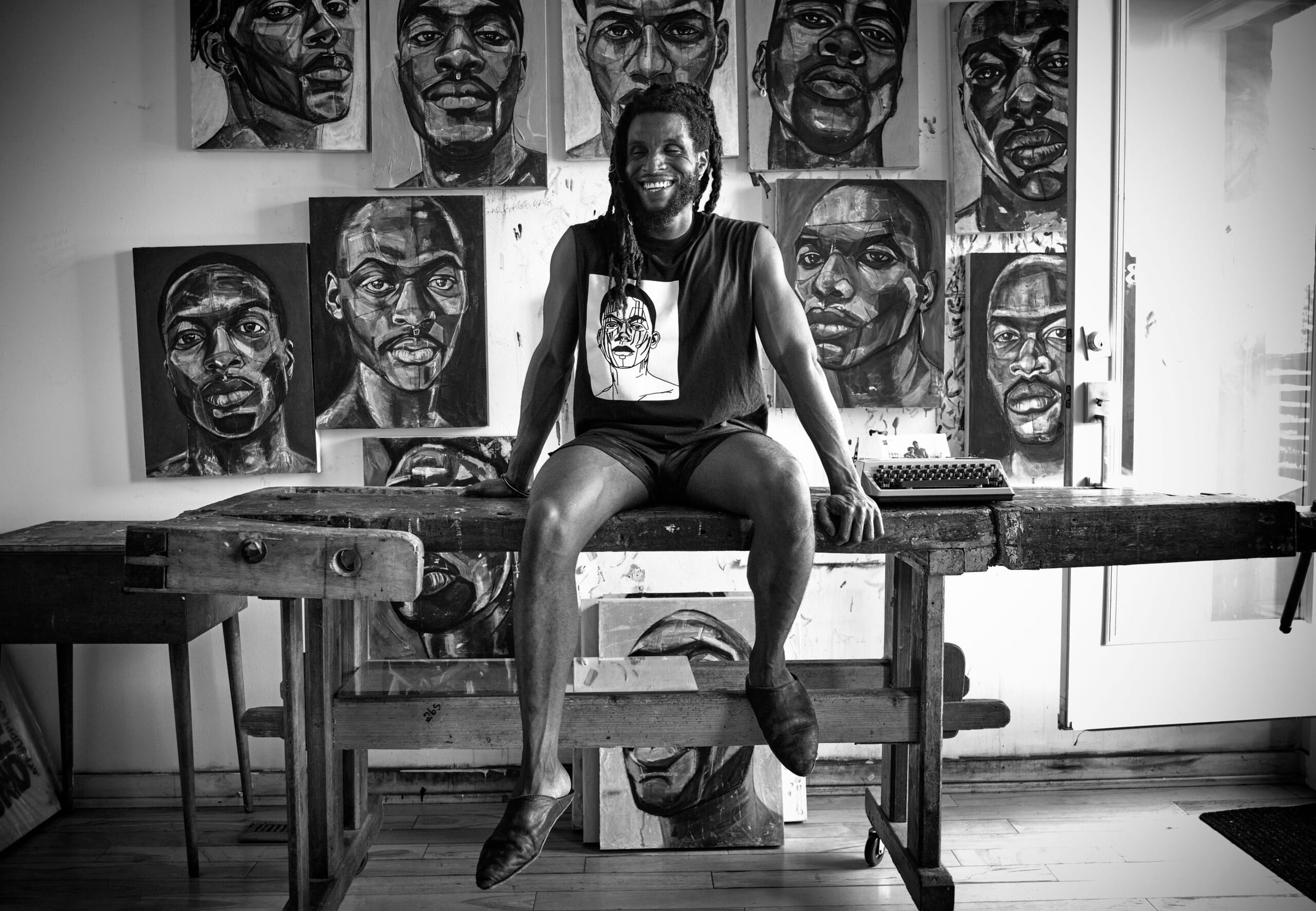

AIR NÖ is a gesture towards the utopian. Open to non-Austrian artists and writers, it brings together an international group in a town of 15,000 people. The curation is deliberate. In my time there, I met composers, sculptors, painters, animators, and photographers from Pakistan, Sweden, France, Russia (by way of Italy), and the US. It is also where I met Ian Strange, a 42 year-old visual artist from Australia.

To open an artist residency to the world is to court diverse geographies, economies, and practices. With an increasingly popular European right stirring anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiments, not to mention the fractured communities of art and literature post-October 7, AIR NÖ felt revolutionary on the one hand, and a privileged bubble on the other.

It’s also been a long time since I’ve been able to knock on someone’s door and say, “Let’s hang out”—male friendships, in that way, become more difficult with age. So, when I invited the black bearded, black clad Ian Strange for coffee, it felt like something… unusual. We met daily to pick apart the world and shoot the shit. A friendship emerged based on shared interests and values. I was compelled by Ian’s journey as an artist, including his recent project Suburban. Part artistic intervention, part photography installation, it speaks to the uncanny experience of home, a subject that spoke to my own experience as a semi-nomadic adult artist. I envied the way Ian could work without words, creating work that spoke to and collaborated with local communities. He continued this trajectory in Krems in ways that surprised and unsettled me.

One day, while sitting at a local café, I overheard Ian talking on the phone—something about acquiring a license so he could shoot fireworks in a field. “What the hell was that about,” I asked, when he hung up.

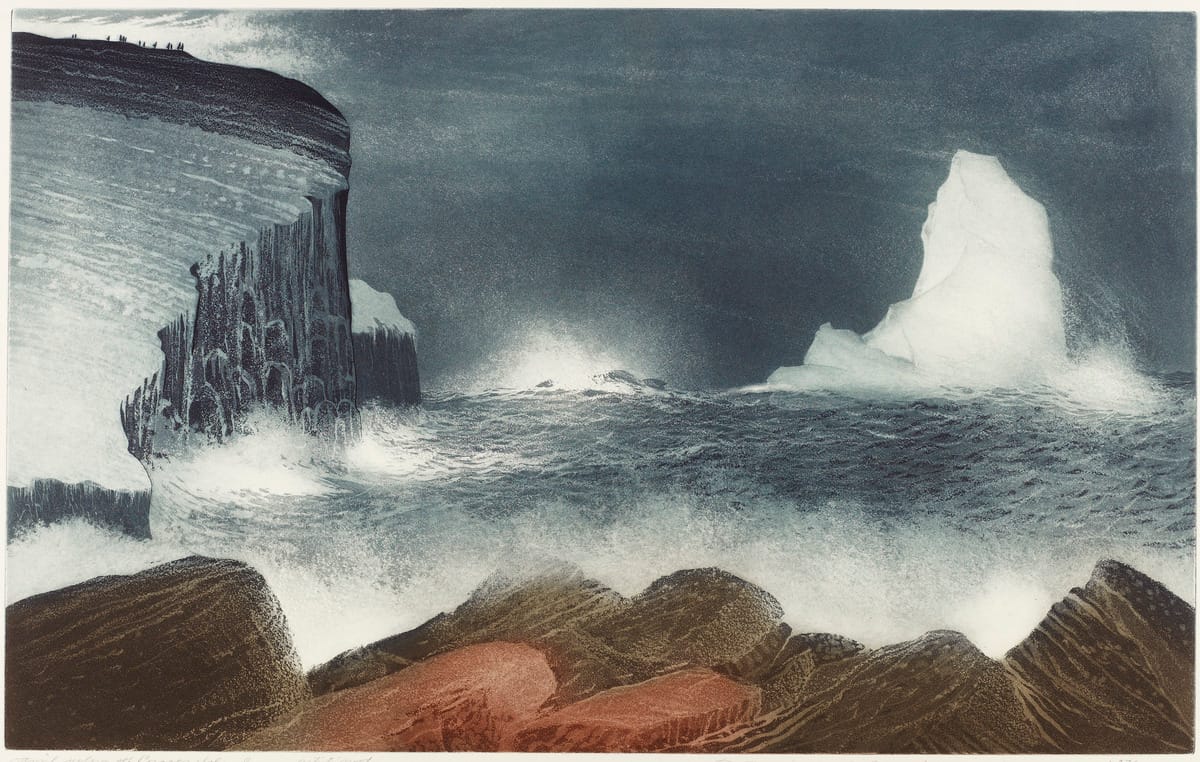

Ian explained how he had long been drawn to international places of conflict and extraction, exploring landscapes where the violence once done has become hidden, like scars imperceivable to the unknowing eye. For his latest photographic series-in-progress, he had already made a piece in Jezerc, Kosova, a village along the frontlines of where Kosovar and Serbian forces battled in the late ’90s. Today, there is little evidence of the devastation and loss that transpired 25 years ago; the surrounding mountains and forest are beautiful and serene. Ian wanted to create images of this bucolic landscape that alluded to the violence which once marked it. To do this, he took photographs at night, using a Nikon digital medium format camera, with fireworks as his source of light—each project named for its numerical geolocation. He sought a language that maintained neutrality.

“Why fireworks?” I asked.

“In part it’s what the firework represents,” he explained while stirring his ice coffee, which Ian drank copious amounts of. “It ties into the history of explosives and gunpowder, technologies of violence.” Ian said the firework is often used to make people look up: by the victor as part of a nation’s mythmaking. He wanted to use fireworks to guide the viewer to look elsewhere.

“You’ll never see the fireworks in the photos, just the light. I like how they affect these landscapes, the light knitted into the frame, coloured shadow. It creates a strange, unsettling effect. It’s pretty cool.”

Ian wanted to make such a photographic intervention here, in Krems, at a former POW camp located on the outskirts of the town.

I did not want to think about Stein Prison, my unwanted neighbour. As someone who has written about the Holocaust, in poetry, plays, and prose, and whose identity is shaped by such events in history, I was intimately familiar with the territory, one that has a knack for drawing me into its unfathomable tragedy. But I was in Krems to concentrate on other things. Namely, a new book.

Yet the more time I spent with Ian, the more his project made me wonder if I was purposefully trying to avoid such histories of violence and atrocity that were now invading the current political moment. Like the cartoonish posters I steered away from during my daily walks along the Danube, ads for the far-right Freedom Party of Austria spouting anti-European and pro-Putin sentiments, I sought to avoid present and past events, blot them out. Ian’s work argued this was impossible. Perhaps Ian’s project acted as a proxy for uncovering things I preferred to ignore.

The POW camp, Stalag-17B, is a 30-minute drive from the residency. It was the largest POW camp in Austria during the war, at one point housing 66,000 Soviet, American, Italian, French, Serbian and Dutch prisoners in feeble conditions. In 1953, Billy Wilder released Stalag 17 about the camp’s US POWs. Later it would serve as inspiration for the TV show Hogan’s Heroes. Interestingly, the film was not released in Austria or Germany until the 1960s because of its supposed one-sided portrayal of the German prison guards. According to the director of Krems Museum, Gregor Kremser, few people in Austria know the movie. This made Ian curious, but also cautious. He does not view his work as that of a journalist, wanting to get “the story.” He did not want to tread on a local history people weren’t willing to participate in. He wouldn’t do it otherwise.

Ian drove with Lisa Sachs, another AIR NÖ project coordinator, to the site of the former camp. What struck Ian when they arrived was there was no way of knowing what happened there. No markers, no memorial plaque, the camp barracks and guard towers demolished and disappeared. He wasn’t sure if he’d found the right place. All he saw were fields of tall grass, farmland, trees, and shrubs. A small airfield, narrow one-lane roads, sealed and unsealed. Tall hills and the sound of wind. A stunning view sloping towards Krems.

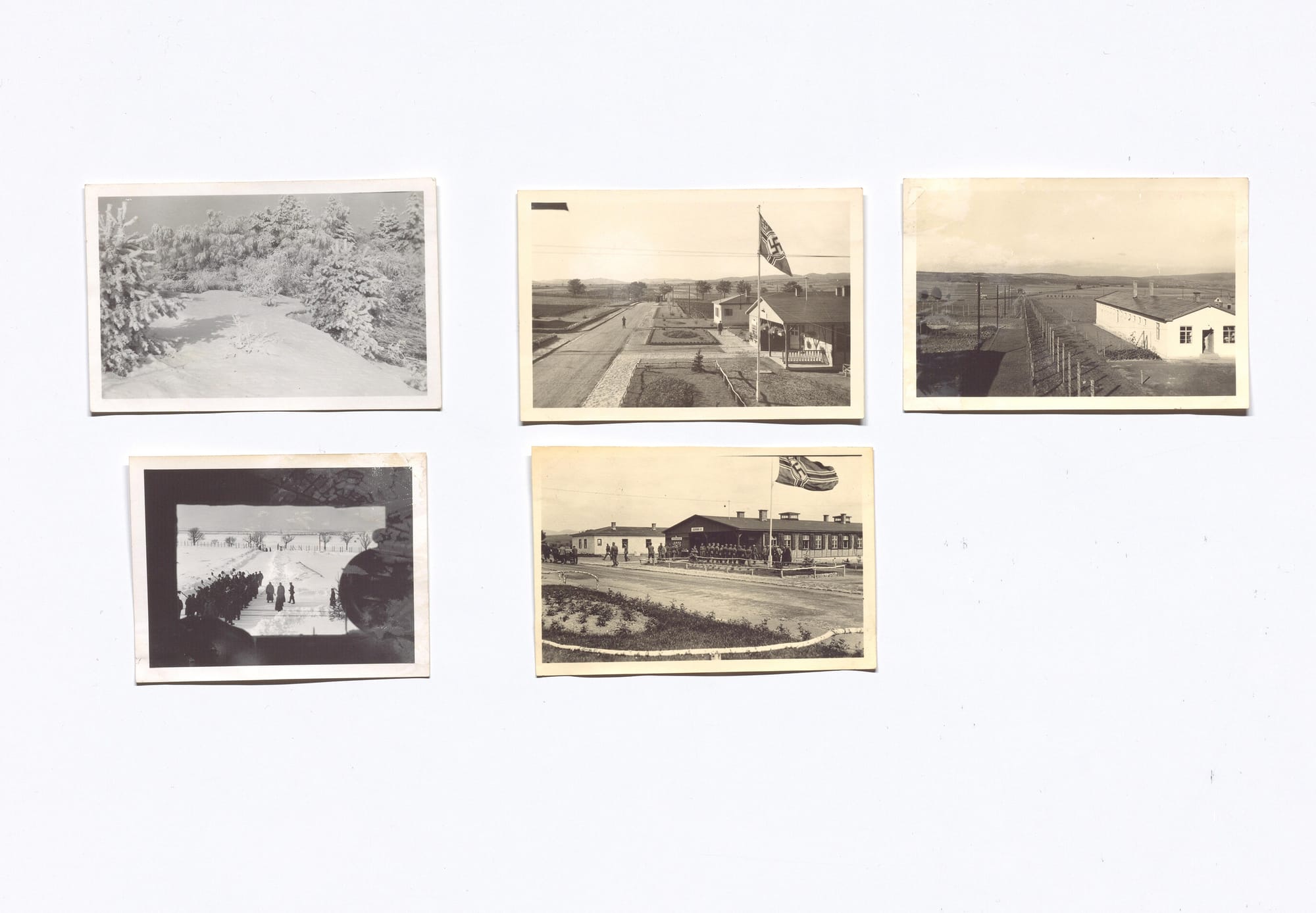

Where exactly was the camp? Why were any markers commemorating its existence minimal, almost hidden? Were people ashamed? Afraid? Had attitudes changed? Upon returning to Krems Museum, Ian was directed to the museum archive, where recently an album of photographs taken by a former prison guard had been donated. The pictures were jarring; they captured both the grim imagery of the camp alongside domestic scenes and ordinary life. They also revealed the same empty fields that Ian saw.

Left, Ian Strange creating his work in Jezerc, Kosovo, 2023 (Photo: Dren Osmani). Firework technicians in preparation for a shoot in Völklingen, Germany, 2024 (Photo: Lukas Ratius).

Kremser led Ian to Karin Bohm and Edith Blaschitz, two academics who happened to be publishing a book called, Nothing to See?: Stalag XVII B Krems-Gneiexnedorf — a Topographical Survey. Bohm had been photographing the Stalag 17B site for the book project, while Blaschitz, head of Digital Memory Studies at the University of Continuing Education Krems, was researching traces of former forced labour camps in the area. Stalag 17B became a central part of her research. The book happened to be coming out that week.

Karin Bohm took Ian to the site of the former camp. Thanks to her, Ian got a better sense of the place, the layout, and history. Together they discussed where Ian would make his photograph. It took multiple visits to decide on the far eastern corner where the camp started, where the barbed wire fencing and guard towers would have been. They believed it best echoed the place where the amateur photographer had taken his pictures 80 years ago.

The night Ian took photographs at Stalag-17B, a group of curious locals came to watch. Because it was June, the days were long. Ian set his camera up at 7 pm. He set his exposure to 30 seconds. He needed the sun completely down, waiting until 10.30 or 11. When he judged it the right moment, he radioed the technician to set off the fireworks, one by one. As the shell of each firework streamed skyward, Ian waited for its tail to leave his frame; then, just as it was about to explode, Ian pressed down on the shutter—the landscape illuminated. The technician set off around 15 fireworks during the night.

There was something intimate about making this kind of work public, an “inverted fireworks show”, as Ian described it. A slow, considered moment. “I think of it as illuminating histories, not celebrating them. Storytelling, instead of spectacle.”

And a gift to me to have participated, in some way, in such a thoughtful act of memorialization. As for the future, there is interest from local galleries in Vienna and Krems to showcase the work alongside the archival photos. Given the current dynamics of European politics, such a conversation is paramount.

Sometimes, late at night in AIR Niederösterreich, I would sneak into the residency office and look out the window across the street at the old prison. I’d like to say I saw something, a clue to understanding the violence of the future, present, and past. In truth, I saw and heard nothing.

Jonathan Garfinkel is the author of In a Land Without Dogs the Cats Learn to Bark.