If Statues Must Fall, Taxonomy Must Also Fall

A conversation with Brazilian artist Giselle Beiguelman about her exhibition Botannica Tirannica—now showing at Koffler Arts—and understanding the colonial imagination.

On name alone, you might mistake Botannica Tirannica for another entry into the illustrious canon of films about monstrous, people-eating plants—what’s called “plant horror” by fans of the genre. As a rule the threat in these films nearly always operates on the level of allegory. With early classics like Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Day of the Triffids, the story of alien plant life taking over allegorized the red scare, and society’s fears of the enemy within. More recently, critics have variously interpreted the 2018 movie Annihilation as an allegory for cancer, humanity’s capacity for self-destruction, and, my favourite, “self-defeat on a molecular level, an entropy of the self.”

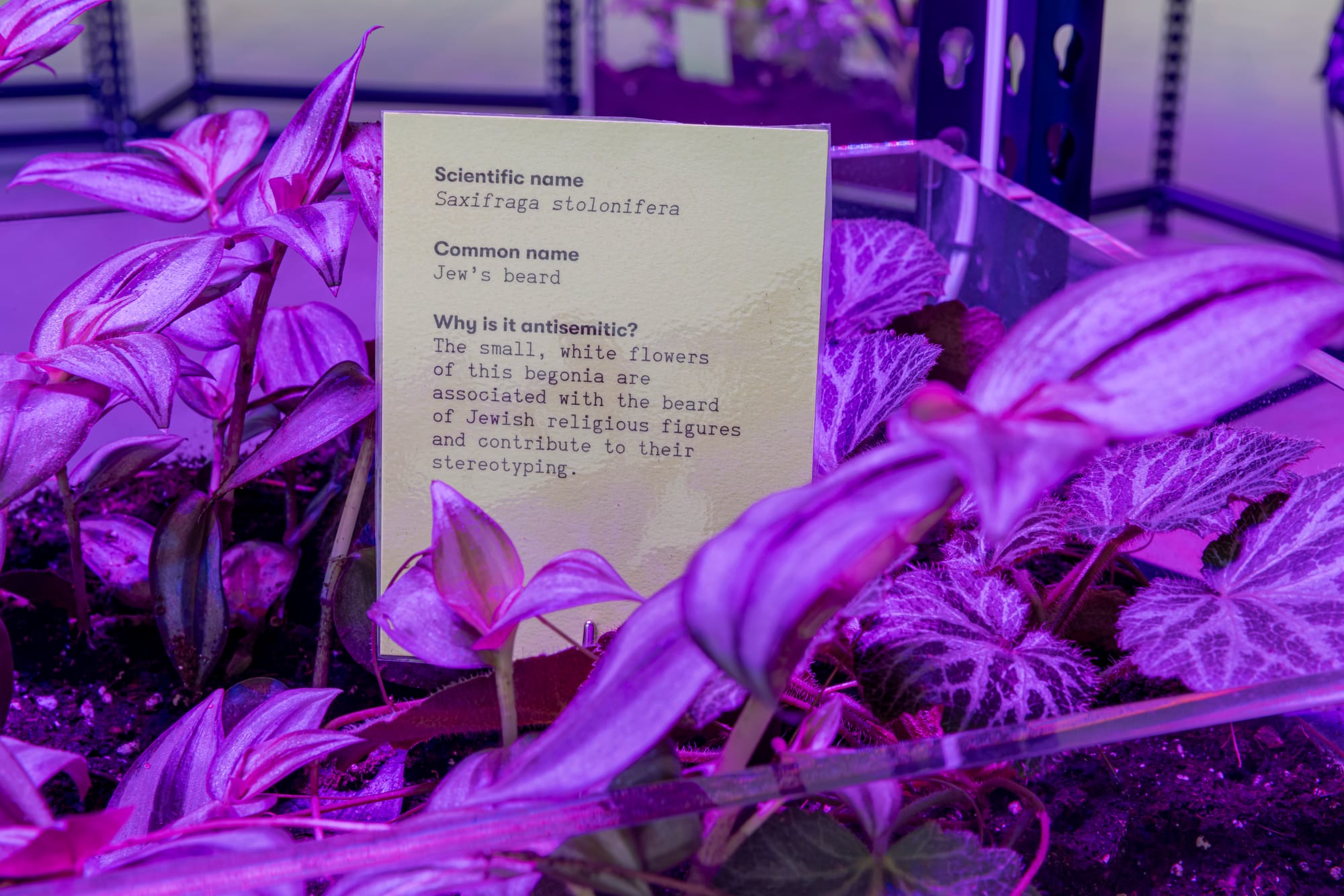

Except with Botannica Tirannica the threat isn’t implied or allegorical at all, but actually quite literal—insofar as the instruments of violence operate at the level of language, nomenclature, and taxonomy, with the plants as nothing more than their innocent carriers.

Created by the Brazilian artist Giselle Beiguelman, the multi-faceted exhibition now showing at Koffler Arts was inspired by Beiguelman’s research into how derogatory references to marginalized peoples have become encoded in both the common and in some cases scientific names given to plants. It all started during the pandemic, when a friend gifted her the seedling of a Tradescantia zebrina—better known by its more unfortunate name, “the wandering Jew”.

“The moment I got in my Uber, I was already Googling ‘wandering Jew,’” says Beiguelman. “Then at home I started looking for more references to antisemitism and taxonomy. In about 15 minutes I realized the problem was much bigger—around plant taxonomy and nomenclature and their connections with colonialism, sexism, and different forms of racism.”

Describing herself as “totally abducted by these questions” around the origins of nomenclature, Beiguelman spent two years compiling cross-referenced databases of problematic plant names, first in Brazil, then further afield. Clear patterns emerged. “You see how the prejudice against groups that are openly oppressed in society, across different contexts, is distributed and naturalized in our most basic activities, like naming plants.”

Such taxonomic practices often did more than just reflect and reinforce demeaning stereotypes, but served a much larger purpose, given how deeply rooted the modern study of botany is in the era of European expansionism and its various imperial projects around the globe. Whether in the Americas, Africa, or Asia, naming and taxonomy was another way of erasing or overwriting the knowledge and lifeways of the native population.

As Beiguelman dove into her research, she quickly learned that, “Already there were debates about these taxonomies, where people argue that if [racist, colonialist] statues must fall, taxonomy must fall too. It’s not something exclusive to my work, but I think I took it to the extreme.”

While the centrepiece of Botannica Tirannica is a creepily sci fi-ish installation of plants, tagged with explanations for their names, the oddly synthetic seeming images of flora arranged on the gallery’s walls add another dimension to Beiguelman’s explorations in taxonomy and colonialism. Here she’s playing with and subverting the methodology developed by the pioneering eugenicist and social Darwinist Francis Galton, whose approach, in Beigeulman’s words, was to “erase the particularities in order to find what he calls the ‘generic’ of each group.” Realizing that machine learning works in much the same way, by whittling away the particularities, Beiguelman used AI to create images of imaginary plant types but halted the process right at the moment before any variations were erased.

Arcade spoke to Beiguelman from her home in São Paulo, shortly before she would arrive in Toronto for the show’s installation.

Before Botannica Tirannica, your work largely revolved around exploring how new technologies are shaping the urban imagination, as well as what you’ve called the “aesthetics of memory.” Was botany something you had any previous knowledge or aesthetic interest in?

My father was a very important geneticist, but he began his career in botany. When I was a child, I was with him in all the botanical gardens and among his microscopes. And my mother was very affectionate about plants, I was raised with many plants around, especially flowers.

But that was something totally connected to my private life. So, yes, this is the first time for botany in my work, and I haven’t stopped. I’m now involved in a new project that was conceived for the updated version of Botannica Tirannica that will be presented in Toronto. What is really interesting for me is to see how this exhibition is connected to all my work in the field of what I call the aesthetics of memory.

Could you explain what you mean by the aesthetics of memory.

I define the aesthetics of memory as the production of languages that occurs in close engagement with history, which uses history as its raw material, not the artistic and cultural production that takes history as a theme, as is very common in literature and cinema, where narratives dramatize events. In this field of the aesthetics of memory, we find, for example, “an archival impulse,” as Hal Foster termed it.

In his 2004 article of that name, Foster argues for the emergence of an archival art, which encompasses a range of artists whose work focuses on historical information, much of it lost or displaced, in order to make it physically present. These artists, according to Foster, “not only resort to informal archives but also produce them,” and, in doing so, create their own worlds.

From my point of view, this is where the difference between archival artists and historian artists lies. Despite sharing several of the strategies of archival artists, historian artists are not as concerned with creating internal logics among the data or with inventing worlds based on symbolic arrangements of objects and texts. Their motto is the demand for a form of knowledge of the present through access to the past.

I believe there is a significant historiographic impulse in the artistic production that comes from the Global South, where struggles for the recovery of the right to memory are a central issue. This is because what is at stake are the silenced interdictions for decades in the basements of dictatorships, narrative disputes, traumatic memories, and the legacies of the brutality of colonialism.

It is with this perspective that projects I have done in recent years, such as Memória da Amnésia (2015) and Monumento Nenhum (2019), among others, dialogue with and question the logics of the politics of oblivion in Brazil, shifting monuments and fragments of monuments stored in depots like piles of lost memories into public spaces.

Two images at left from the series "Poisonous, Noxious, and Suspicious," a new addition to Botannica Tirannica for its Toronto staging. (Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid) Right, Giselle Beiguelman during the show's installation. (Photo: Jeremie Warshafsky)

In addition to the plants you’ve selected and annotated for presentation, there are films and two separate collections of imagery that were produced with the help of AI. What was your artistic process for transforming these ideas about taxonomy, colonialism, and plants into the various mixed-media elements of the exhibition?

At the same time I was captured by this research, I was taking my first steps in developing images with artificial intelligence—so it was a kind of confluence of the two research paths.

In AI, the machine learning process is a process of erasure of particularities, especially when you talk about the neural networks that are popularly used in the making of deep fakes, for instance. The system searches for the generic and hidden patterns of the image in order to conceive the deep fake. In this process, all particularities are erased.

It’s amazing because it’s so similar to the methodology that Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, used to develop his theory. He created a method where he is making the composite portrait—to superimpose a lot of pictures and portraits on top of each other and then erase the particularities in order to find what he calls the “generic” of each group.

For Botannica Tirranica, I was trying to build a kind of counter-hegemonic model. When I was training my machine learning models with images of plants, I would stop the process the moment before the model began to match all the characteristics and erase the variations. I was also asking myself if it was possible that artificial intelligence could point to another conception of nature, and the relation between culture and nature.

This was how I was working most of the time with Botannica Tirannica, and it was very important from an aesthetic point of view to insert these super synthetic images, made with AI, in a garden. So the exhibition is a kind of greenhouse where you are with the [living] plants but also these totally abstract, synthetic images. It’s common to see visitors to the show trying to figure out, “Wow, which plants were used to create this hybrid,” because there is still something about them that has a connection to a real image. But they are so different feeling at the same time. That was my goal, for them to be in this limbo between real and potential images.

There is definitely an “uncanny valley” feeling to those images.

The uncanny valley theory I took very seriously, that point where everything will be so “real” that it will be more real than reality.

These plants are imaginary and in some sense they are even utopias. They are the possibility of dealing with a new kind of imagination where these ruptures or borders between nature and culture we are used to would be completely nonsense. This is very typical from the perspective of Indigenous knowledge, this cosmovision that doesn’t accept the structural divisions that were imposed on it by the colonialist imagination.

What’s interesting about your use of AI is that it functions on two levels—there is the critique of the way that AI and machine learning systems can echo the earlier scientific and colonial mode of classification and categorizing, but then you're just as much using AI is an opportunity to explore ideas about hybridity and metamorphosis.

One of the main problems of artificial intelligence has to do with terminology, and how you even define artificial intelligence. The anthropocentric mind, what you think makes us human, says that we are intelligent and supposedly other life beings are not. The first mistake is to understand artificial intelligence as some improved form of being human.

When Donna Haraway was writing in the ’80s and ’90s about the cyborg, and the dissolution of the boundaries between what is human, animal, and machine, a lot of people considered it, “Oh, this is so naive.” Now it’s becoming real. There is no sense in talking about the competition between humans and machines, but to understand which different kinds of beings we could be when we are not anthropocentric anymore, but are connected to different systems of intelligence, including plants and other animals. So there are other forms of intelligence besides the human way of organizing the world.

(Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid)

Obviously, there’s much about the structures of colonialism and empire that have been replicated from territory to territory across time. But these structures and institutions often take on a different form locally. The Canadian experience of colonialism is different from Brazil’s, for example, at least in the ways that Indigenous and non-settler peoples were administered by the government. Were these ideas you were thinking about as you were conceiving the exhibition?

In the beginning, I was surprised at how the common, vernacular nomenclature was molded by local cultural prejudices. For instance, in Brazil, there are an amazing number of plants that reflect this macho view of the world, and also many that sexualize Black women. In the United States, there are anti-Black names, in Germany and in Sweden a lot of antisemitic names. And in Canada, no surprise, an incredible number of plants with very derogatory names toward Indigenous peoples.

This incursion into Canadian history and flora was surprising to see when contrasted with Brazil. The genocide of the indigenous populations is also part of our history, but we have such a peculiar way dealing with it that 80 percent of our flora are still called by their Indigenous names—jacaranda, ipê—all those names are Indigenous names.

When you go to Canada it’s something totally different. Indigenous knowledge was largely erased from the popular naming of plants. At the same time appropriation was a means of transforming the cultural symbols of Indigenous populations into national symbols.

What were some of the practical challenges in re-staging the exhibition, from the Brazilian to the Canadian context?

It’s very difficult taking an exhibition like this from Brazil to different countries. Living in São Paulo, it’s easy for us to find and buy plants that we need for our garden. You just go to the market or to the streets and you can find what you need. It was more complicated in Europe and by far it’s far been the most complicated in Canada. In São Paulo, there is always a tree in your way and the wildness of nature fighting against culture all the time. You see the plants coming up through the sidewalk because of the rain.

Many botanical gardens, like Kew Gardens in London, are now reckoning with their historical role in supporting the imperial project and shaping our knowledge of the world through a racist or anti-Indigenous lens. Were you following these debates as you worked on Botannica Tirannica?

For the botanical gardens especially, this thing is more complicated because they do not just hold the names, they hold the memory of the extractivist past, the role of botany in colonial extractivism. Going to Donna Haraway again, she says that we shouldn’t be calling it the anthropocene, but call it the plantationocene, because the plantation is the first moment of confronting the environment, and the botanical garden is the place of memory of that violence.

It’s easy to understand the connection between slavery and violence, because it’s visible on the body. But it’s not easy to understand the violence of the botanical garden because we have this romantic approach to plants and, of course, plants can be very beautiful. In a way, this is another anthropocentric mistake. Plants feel, they think, they communicate. And so the debate is very important and it crosses many fields.

It’s not so easy to understand the colonial mind. This is something I only understood after many years of research, not from the point of view of theoretical debates about colonialism, but the colonialist imagination and how it is entangled in our visions of the world, and our daily life.

This is, I think, the most important thing about Botannica Tirannica.