“It is a blessing to turn a nightmare into a good dream”

Manuel Herz, the Basel-based architect behind a new synagogue on the site of the Babyn Yar massacre, challenges prevailing notions of memorialization in architecture.

Rather than shy away, Manuel Herz is more likely to embrace the messy paradoxes and conflicts that are often at the heart of architectural practice. “What we have to realize is that as architects,” he says, “whatever we do, it never comes without negative repercussions.” No matter how well-meaning or utopian the intentions, he adds, architecture is by its nature intrusive, even violent. “It’s an aggressive activity—construction is this cutting away of things, destroying of things, people get displaced. We dig up a lot of dirt and also a lot of history, sometimes making it unreadable.”

When Herz was commissioned to create a commemorative structure at the site of Babyn Yar, the ravine in northwest Kyiv where over two days in September 1941, following the Nazis’ taking of the city, 33,771 Jews were murdered in one of the largest single massacres of the Second World War, he looked to the fundamental contradiction about monuments famously identified by Robert Musil in 1927: “what strikes one most about monuments is that one doesn’t notice them. There is nothing in the world as invisible as monuments.”

Musil’s meaning, of course, was figurative, in the way that monuments over time recede into background; the locals possessing, at best, only a generic sense of why it was ever put there in the first place, however frequently it may be used as the backdrop for political rallies or official state events. For Herz, the problem with monuments, what often makes them invisible, is exactly their monumentality—their unerring reflex toward somber minimalism and stone-cold heaviness. As though these were the only moves adequate enough to convey the desired depth of feeling.

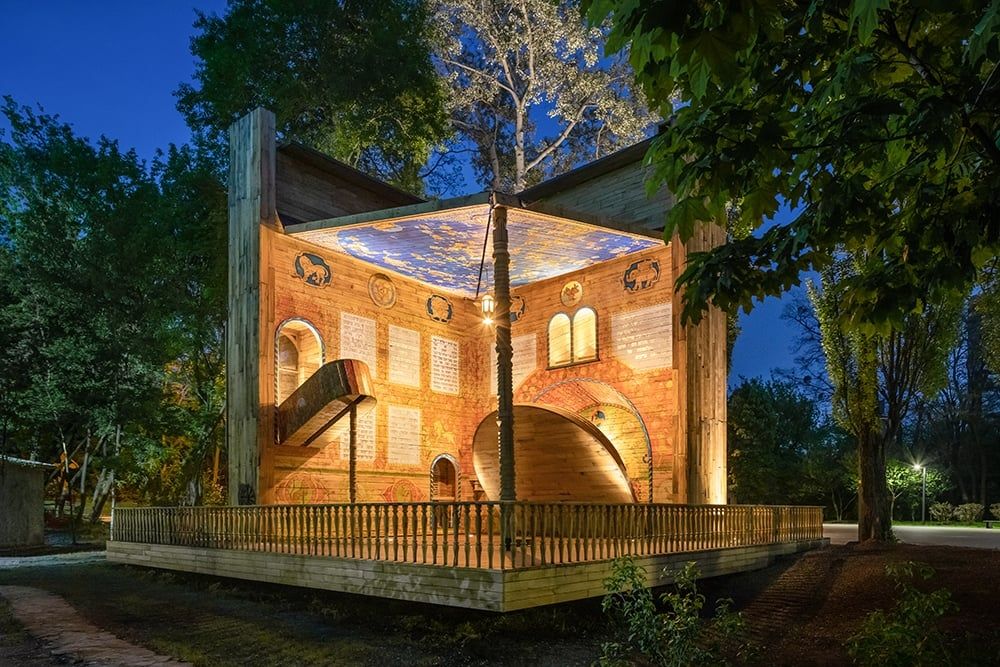

At Babyn Yar, Herz has commemorated by lighter, more playful means, designing a synagogue that not only revives a lost tradition of wooden synagogues once native to western Ukraine, but a moveable one that opens and closes its walls like the covers of a book—the Siddur, or Jewish book of prayer, to be exact. Were it rendered in the style of a pop-up book.

“I wanted to create a project that has a transformative dimension and establishes a new ritual on the site,” says Herz. Part of that ritual now includes the synagogue’s opening and closing, which unpacks from its flat, shut position into a colourful, three-dimensional space using the manual effort of congregants to move its retractable walls. The ceiling, balcony, central column, and raised prayer platform also fold out from the structure.

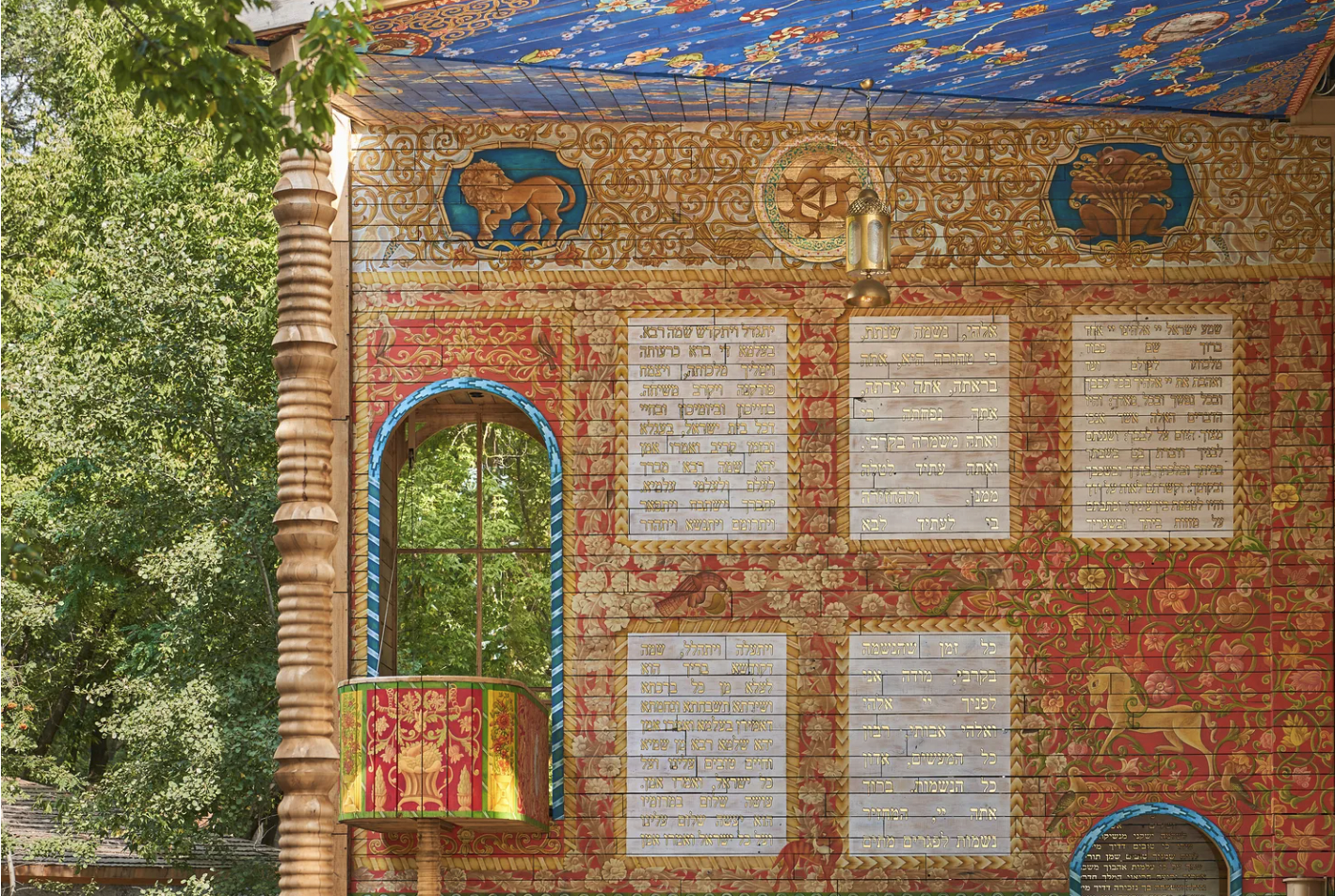

Painted panels of text featuring prayers and blessings, symbolic animals, and imagery from the Jewish zodiac adorn the walls in a unique decorative style once common to synagogues in the Pale of the Settlement. The ceiling is perhaps the structure’s most directly commemorative gesture, mixing floral and astrological motifs to recreate the night sky above Babyn Yar on September 29, 1941—the day the shooting started.

Much of Herz’s architectural work could be described as being in dialogue with the past, making history in some way more readable without being trapped by it. Past projects include a Jewish community centre and synagogue in Mainz, Germany, sculpted out of letters from the Hebrew alphabet, and a Zurich residence called “Ballet Mécanique” that employs a system of petal-shaped louvers to create a moveable structure that anticipates his approach to the synagogue at Babyn Yar.

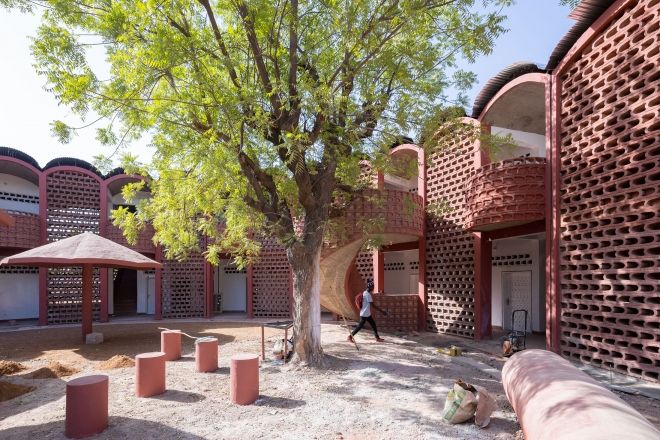

Herz is also co-editor of the 2015 book African Modernism, which recounts the style of modernist architecture that emerged in West African countries during their early years of independence—a style which bares its traces in Herz’s own elegant design for an obstetrics and maternity hospital in Tambacounda, Senegal.

The creation of the new synagogue at Babyn Yar is currently the subject of an exhibition showing at the Koffler Centre of the Arts. Arcade recently spoke over Zoom with Herz at his home in Basel, catching him just as he was putting his son to bed.

(Photos: Iwan Baan)

With the new synagogue at Babyn Yar you’ve gone very much against the grain, in terms of the monumentality and weightiness that's often associated with memorial architecture. Was that your thinking from the outset?

This idea of lightness came quite instantaneously. Very early in the design process I thought let's do something that is transformative. Let's do something that is playful. Let's do something that is not the typical heavy concrete or stone monument.

Part of that was deciding to build with wood—centuries-old oak that was sourced from across Ukraine. Obviously, wood requires a degree of care and maintenance more so than other building materials.

Maybe it's the most unusual material to use for commemorative architecture, we hardly know of almost any formal memorials that use wood. I should note that the Babyn Yar synagogue is primarily not a memorial, it is a synagogue. But it also has commemorative functions. In a surprising way, the use of wood goes to the very core of what it means to commemorate, what it means to remember, because we have to take care of it. We have to cherish it, take care of it every day. It's the very act of remembering that is practiced.

What happened at Babyn Yar has been somewhat addressed in music and literature, most notably through Yevgeni Yevteshenko’s famous poem, Shostakovich with his Symphony No. 13, and Anatoly Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel. How can architecture and the spatial arts memorialize differently than these other art forms?

Well, because it affects different senses. The music of Shostakovich has had a profound impact on me, but I don't know, you can't smell it, you can't touch it. It has a very different impact on our senses. The wonderful, amazing thing with architecture is that we can really touch it, we can smell it, we take it in through our senses in ways that are quite different from music or literature.

Coming back to your previous question, we know of monumental architecture that wants to overpower or overwhelm the viewer, make them feel small. I hope the synagogue that I've designed for Babyn Yar impresses without rendering you speechless, in both the literal and the metaphoric sense. We see how many memorials present a quotation or some sentences you’re supposed to read, and these sentences are often laid out in a central perspective, as though there's a kind of ideal spot from which you are supposed to perceive the monument. It works on a kind of central perspective with some statement that you are supposed to read and be enlightened by.

The synagogue at Babyn Yar works very differently. There is no ideal single place from which to perceive it. You can wander around it and, because it transforms, there is no one kind of configuration that is better compared to all the others. And obviously there are many texts, not just one. Some will be able to read it, some not. There's so much iconography that you can choose to decipher it or not.

It's not this didactic architecture that tells you what to understand. There are many, many messages that you can perceive, and this open-endedness. This is extremely important because of the tens of thousands of lives that were extinguished on those two days, and then in the following weeks. We don't want to reduce it to a single story. Every life is a story, if we can use that word, that was cut short in a terrible way. It cannot be reduced to a single sentence.

At what point did the pop-up book occur to you as an inspiration?

My wife had just given birth to this wonderful little boy, my son, literally a week or two before I got the commission. Maybe I was going into it with this mindset of playfulness, with all these little toys around. So the idea came very early in the design process.

I was also remembering an unrealized project by an architect I admire, John Hejduk. It was quite a speculative project that he proposed for the former Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. Instead of proposing, again, this heavy kind of monument, he proposed a sequence of 36 little interventions that were playful, and he drew them in this light, sketch-like way. These were things you might find on a children’s playground. So I remembered that project when I started on Babyn Yar, thinking that's the right approach.

Sometimes you're lucky as an architect. And in this case, I was really lucky. First of all, getting the project was an incredible honor, to build on Babyn Yar, which is really one of the ground zeroes of European history, it’s one of the places, spaces that defines European history. But I can also say I was lucky in having an idea that turned out to have a very rich potential.

What was unique about the synagogues of western Ukraine, now all destroyed, from which you drew inspiration?

You had in the Pale of Settlement a unique architectural style that emerged in the 16th century up until the 19th century, of wooden synagogues that were often colourfully painted inside, though we have very few photographic records. Without wanting to simplify, the Jewish nation, at least until the 19th century, was not famous for its architectural production, it didn't have a very extensive architectural culture, or building culture. It often used borrowed architectural styles for its own synagogue constructions. But one could claim that in western Ukraine and the Pale of Settlement quite a unique, quote-unquote, “authentic” Jewish architecture emerged that stands on its own two feet.

I thought that this is a brilliant reference because it is unique to western Ukraine, southern Poland, and so on. And because it's so beautiful. I thought, how can we reinterpret it, reshape it in a contemporary way? So you see what we tried to do with the design of the ceiling and the walls.

One of the texts on the walls reads, in Hebrew, “It is a blessing to turn a nightmare into a good dream.” You’ve described this as the work’s leitmotif, from the Jewish idea that the best way to honour death is to celebrate life. What was the source of that text?

I found it in a historic photograph of one of those old synagogues. My Hebrew is not very good so I asked a friend to help identify the text in the photograph. He came back saying it's quite an obscure blessing, referencing a Talmudic text on the interpretation of dreams and, and more specifically this idea of turning a nightmare into a dream. I was almost shaking when I read it because it was exactly the quality I wanted to convey through the synagogue. I truly believe that the best way maybe to honour the dead is to celebrate life.

We have to be careful with this idea of commemoration. If we only remember the dead by repeating the story of death and dying, we just get stuck in the terrible crimes the Nazis committed. We have to go beyond that.

The Mainz synagogue and community centre designed by Manuel Herz. (Photos: Iwan Baan)

You had worked in the context of sacred architecture at least once before, with the synagogue in Mainz. But the question of how to approach memorialization and remembrance through architecture—was that something you had thought much about prior to the Babyn Yar project?

I recently had a conversation with another architect for the Italian publication Domus where we went through the three synagogues that I'm involved in—the Mainz synagogue, Babyn Yar, and an ongoing renovation project in Cologne—and basically you can identify three very different approaches to memorialization.

The new synagogue in Mainz stands on the site of a former synagogue that was destroyed just before the Second World War. It would have been quite obvious to memorialize the previous synagogue in the new construction. But I didn't want any kind of memorialization of the old synagogue, nor any kind of memorialization of the Holocaust in the new synagogue. For two reasons. First, I didn't want the destruction of the old synagogue to be part of the new design, maybe out of stubbornness. I didn't want the Nazis to be in any way co-authors of my new synagogue.

The other reason was that it's not at the location of the Jewish community where the Holocaust needs to be remembered. The Jews of Mainz are maybe the last people who need to be reminded of the horrors of the Holocaust. It's the general population of Mainz who need to be reminded. So if we commemorate the Holocaust in Mainz, it should be on the central square, but not in the synagogue.

With the Cologne synagogue, which I'm renovating, refurbishing, transforming, it's more about carving away and uncovering the physical layers of history physically in that building. It's a building that was built in the late 19th century, semi-destroyed in the Second World War, and then reconstructed after the war and changed quite fundamentally. But its core walls still date back to 1895.

It may be the only synagogue in Germany that dates back to pre-war and is still used as a synagogue today. We are literally carving the layers of plaster away to see what traces of history we can kind of uncover from the last 120 years. If we find something we are kind of preserving that, and adding new layers of authorship from my design.

How did you first become interested in architecture and decide to pursue it?

I mean, it doesn't run in the family. My parents were not architects, but I had what you would call in German a Bildungsbürgertum, this idea of a cultured education. My parents took us to see buildings and took us to concerts and so on, and maybe this laid a certain kind of seed. What fascinated me, I guess, is that architecture is a very public art, it’s a practice where you can really affect a large part of the population. It combines philosophy, mathematics, and artistic practices, while still providing function and use.

You’ve said in interviews that you’ve never been interested in developing any sort of consistent formal language as an architect, or formula you could replicate. What would say then has been the main through line or preoccupation across your work?

I'm very interested, of course, in form. So that there's no misunderstanding, many of the projects that I've done have a certain kind of sculptural quality or expressiveness. I'm interested in exploring that. But they also have joyfulness or sense of playfulness, while somehow also being quite strict and simple in their geometry.

Obviously, you develop certain interests that sometimes you want to try out again. Babyn Yar isn’t the first building I've done that has a transformative quality, or transformative elements. I did a small housing project in Zurich, where the facade can also kind of fold and unfold, but it’s a completely different use, completely different context, completely different function, a completely different formal expression.

But then there's the idea that hopefully runs through most of my architectural projects, of trying to explore and to a certain extent question conventions and preset rules, and thereby use architecture as a tool of research and investigation. How can we do architecture and also learn something about the underlying process, about its history, about how to look at something like synagogues in a completely different way? How can we use architecture now to tell the story of memorialization in a way that it has maybe not been told yet? This kind of questioning of conventions is something that I find interesting and challenging.

In the 2000s, you began travelling in Africa and pursuing your own study of refugee camps. What drew you there and how did that research shape your practice?

Two or three things came together. One is connected to the notion of diaspora and displacement. This question of diasporic exile is a very interesting one in the context of architecture because it immediately challenges architecture—this sense of uprootedness, of not immediately having your roots in a place, challenges, in a way, one of the basic assumptions of architecture, which is to be rooted in one place.

So how do people who are uprooted build their own spaces in exile? That's a question the Jews have been struggling with for the last 5,000 years. It's quite a wonderful story to tell in a way. In a contemporary context it's a story of refugees, and how these places are built that give them a temporary home. You could have a congregation of 100,000 refugees in one spot for five years, 10 years, 15 years, 50 years. This is something that I was interested in.

And then in the late ’80s and ’90s, there was this Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agamben, who became quite popular. He wrote quite a lot about “the camp” as a paradigmatic place for representing 21st century biopolitics and so on. Agamben became widely read in the architectural community, or at least amongst a certain crowd. I was very skeptical of what he was writing. I thought this guy has never been to a refugee camp and constantly writes about it. So I just thought let's see for myself what they look like.

Those were the starting impulses that led me to look at them. I went to Central Africa for the first time around 2005, and on a practical level these considerations had not yet really arrived in the architectural community, like, how do we build spaces for refugees? It was discussed on a purely technical level, and so some of my friends looked at me and, and said, “Yeah, sure, that’s interesting, but what does it have to do with us? Why should we care?” A few years later, with the refugee crisis getting worse and worse, these things becoming more and more urgent, we find ourselves in the middle of it as spatial practitioners.

Obstetrics and maternity hospital in Tambacounda, Senegal, designed by Herz. (Photos: Iwan Baan)

So there’s a resonance for you, between the synagogue at Babyn Yar, and the Jewish experience of displacement, and your broader interest in migration and exile today? There’s the obvious symbolism of the synagogue folding out like a book, and it being the book through which Jews, however dispersed, find community. These connections were evident to you as you thought about the design?

I can only say yes, that these are thoughts that are important to me, that I've worked on and written about, that somehow whizz through my head when I work on architecture.

Earlier you referenced the birth of your son—how it coincided with the start of work at Babyn Yar, and even helped push it in a lighter, more playful direction. Would you say that’s also true of your practice more generally?

What is wonderful about architecture is that we are one of the few professions that have the ability, and therefore maybe also the responsibility, to make the world a little more beautiful, a little more fair, and a little more just. We shape our environment, we are active agents. Beauty, that's a huge term and we should take it in the broadest of all senses, as a quality of life. It's something that we need, as much as we need food and love, air and water.