The Meaning of a Space: Where Do Toronto’s Artists Go Next?

As the dwindling number of spaces vital to Toronto's working artists continue to struggle or turn to rubble, Josh Greenblatt investigates the multi-fronted policy response it will take to enable artists to thrive as more than a civic afterthought.

In October 2021, the developers who bought 888 Dupont St in Toronto finally emptied the building of its remaining tenants. Notorious for both its parties and its squalid conditions, the century-old former factory was one of the last buildings to provide affordable arts spaces in the city. Rosa Halpern, a clothing designer, and her carpenter husband lived in the building from 2016 until 2020, paying $2,400 in monthly rent for almost 2,000-square-feet of live-work space, which they split. It was thanks to the relatively cheap rent that Halpern was able to get her business in custom leather outerwear off the ground, though the support of the building’s tight-knit creative community also helped.

When Halpern’s business eventually outgrew the studio on Dupont, she found a space in the city’s west end large enough that she could bring both her production and showroom under roof—albeit a much more expensive roof. “We can barely afford our current rent and already we need more space,” says Halpern. With her lease up next year, and rents for studio spaces still skyrocketing, Halpern will be forced to move her production facility outside of downtown. At least Halpern is able to remain in the city; many of her peers have fled altogether. “It’s unfortunate, but that’s the reality of Toronto right now.”

When demolition of 888 Dupont finally began last fall, it was just the latest in a growing number of formerly artist-friendly buildings on their way to becoming high-end residential or commercial developments. It’s difficult to find hard numbers, but due to the soaring rents and relentless condo development, affordable studio space continues to dwindle throughout the city, leaving artists, along with small arts and cultural organizations, increasingly scrambling for options. This is a reality that is helping to suffocate the city’s visual arts scene.

For almost 40 years Artscape has been one of the few organizations of any significant scale providing the city’s artists with affordable studio spaces. When it was announced last August that the organization would be entering bankruptcy proceedings it came as a major blow to the city’s artists—signalling an even deeper sense of precarity within Toronto’s cultural ecosystem, in which Artscape had long played a pivotal role. (In January 2024, after formally applying for receivership, Artscape outlined its transition plan, assuring tenants and communities in many of its buildings they would experience “limited disruption”.)

Artists Matthew Schofield and Gillian Iles shared three studio spaces before finally landing at Artscape Youngplace on Shaw St., where they’ve rented a studio for the past 11 years. (The building is also home to Koffler Arts.) “It was a good decision, a good move, because [Artscape] was a stable organization,” says Schofield wistfully. Unlike the pair’s previous space at Artscape Liberty Village, the non-profit arts organization owned the building at 180 Shaw St., giving it a measure more of long-term security. The former public school is close to Trinity Bellwoods Park and the packed restaurants and shops of Ossington. “We thought ‘Perfect! We are now in a studio that will be here forever, until we decide we want to move, or we want to leave.’”

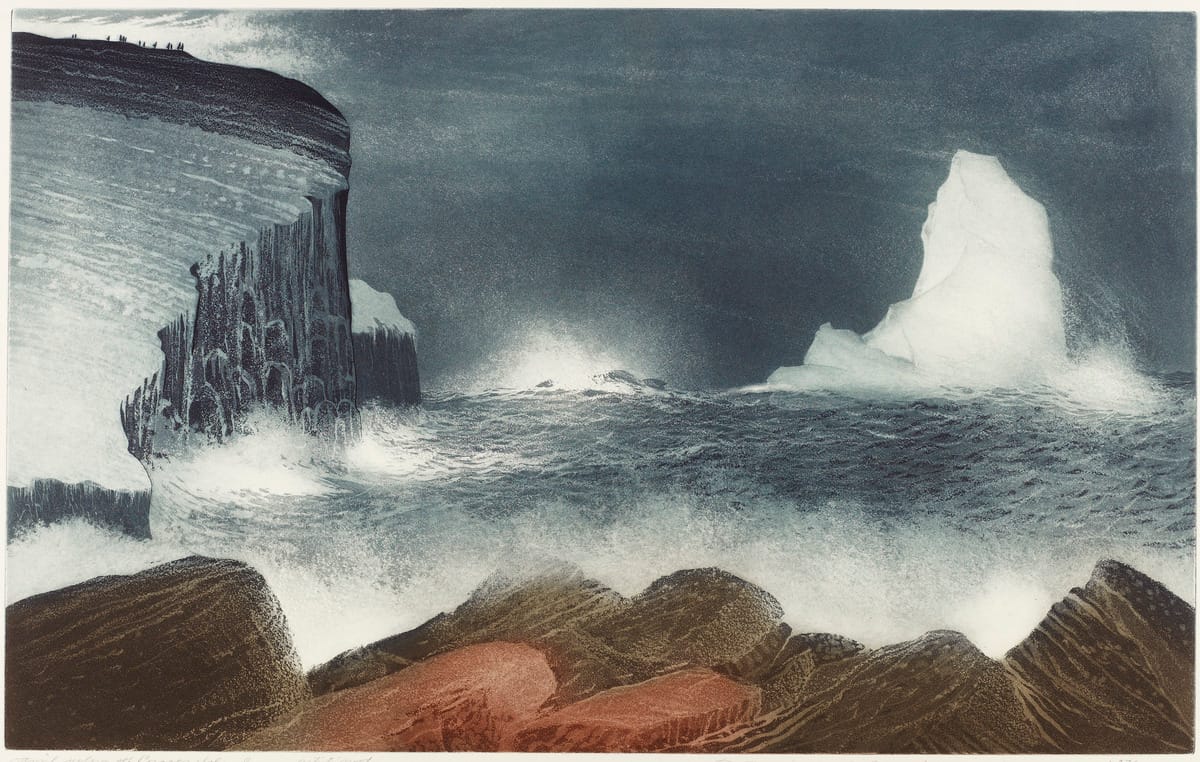

Unfortunately, many of their artist colleagues have had less luck in the quests for affordable space. “We’ve seen our friends move to different cities,” says Schofield. “It’s not just the lack of studio space, but the affordability of housing.” Both Schofield and Iles are exhibiting work in DECADE, Koffler’s current exhibition surveying the last 10 years of artmaking at Artscape Youngplace.

Jason Samilski, the managing director of Canadian Artists' Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens (CARFAC) Ontario, the national association for visual artists, points to 401 Richmond, the arts and culture hub run by urbanspace property group, as a more viable model to follow—in part because there is only one building to manage, rather than a whole portfolio of them. Margaret Zeidler purchased the building in 1994 for what now seems like the paltry sum of $1.5 million. Artists and arts organizations pay below-market rates but enough to help cover operating costs, property taxes, and a reasonable return on investment to fund further building improvements. Technically, the building is privately owned, but urbanspace CEO Vicky Rodgers says it operates more like a non-profit. She points out, however, that the cost of land, and associated property taxes, makes it prohibitive for such a model to work in today’s environment.

Of course, models like Artscape and 401 Richmond do nothing to help artists’ other major challenge—the lack of affordable housing. Nor do they help address the underlying problem, that most visual artists in Ontario are now living below the poverty line.

Barbara Astman, who is also exhibiting work in DECADE, has a long view of how economic headwinds have impacted Toronto’s art scene. Since the 1970s, Astman has rented numerous studios across the city (Niagara St., Dundas West, Wallace Ave.) and experienced the same five-year cycle of renting and eviction countless times.

Still, her complaint lies less with enterprising landlords and more with the lack of meaningful action from the various levels of government, who all tout the importance of the city’s cultural industries and position Toronto as a major arts hub to attract tourists. “What have they done about tax incentives,” she asks, rhetorically. “What have they done about artists who are in studios that are deemed commercial and who have to pay commercial tax rates? Nobody's really lobbying the government to solve this problem.”

Pat Tobin, general manager of the City of Toronto’s office of economic development and culture, insists that supporting artists remains a priority. “Artists are key to social, cultural, and economic development,” he writes in an email, “providing a wide range of services, amenities, educational opportunities, experiences that contribute to mental health, placemaking, civic engagement and social cohesion.” He notes that overall city funding for cultural grants has increased 49 percent since 2013.

To address how rising land costs and usage changes have displaced artists and shuttered arts spaces, the City is experimenting with a Cultural Community Land Trust, which aims to establish and preserve spaces for arts and cultural organizations in Davenport Ward 9—a west-end neighbourhood that still retains many of its old warehouses, heritage buildings, and converted industrial spaces.

In 2022, the city launched its new Office of Creative Space, which promises to develop “a new model for community-owned, artist-stewarded creative spaces for communities to live, work, learn and thrive in a network across the City of Toronto.” While the office is still in its infancy, Tobin insists it shows that the city “recognizes [affordability] as one of the most significant issues facing the creative sector in Toronto.” Beyond the new land trust, however, the city has yet to come up with any other interventions—at least on a major scale—to create more accessible space.

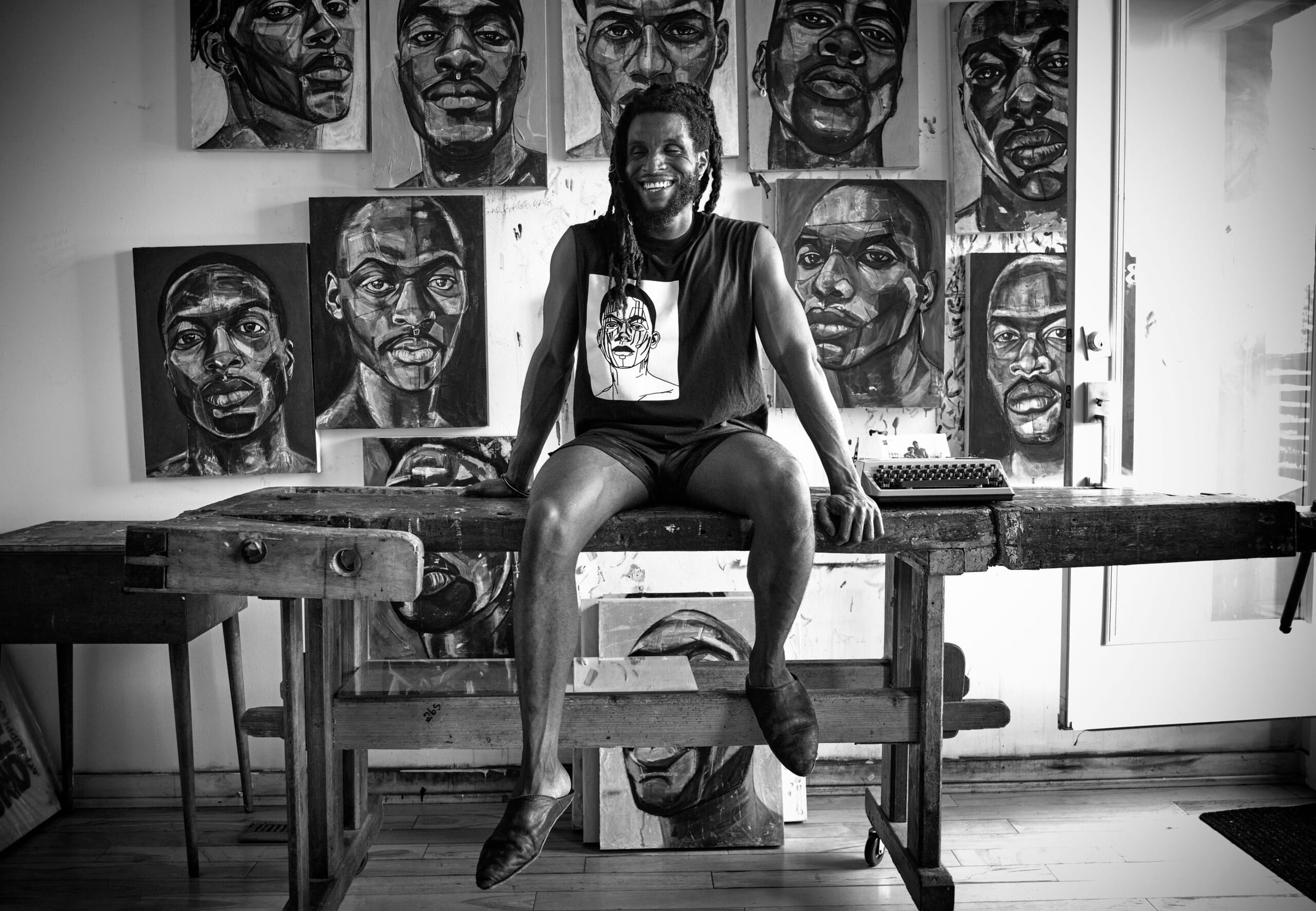

Other organizations are doing their part to address the crisis. Akin Collective is an artist-run organization that receives funding from the City of Toronto focused on providing affordable shared studio space, with members paying according to the amount of area needed. The city also has a capital partnership with Nia Centre, a not-for-profit arts centre that supports artists from across the African diaspora.

According to a 2020 report from Statistics Canada, Ontario’s arts and culture sector contributes about $11 billion to Toronto’s GFP, and $28 billion provincially. But the cost of housing, inflation, and funding cuts are choking the sector. CARFAC’s Samilski further underscores how these economic conditions disproportionately affect racialized, women, and Indigenous artists. One of the problems with the Artscape model, he says, is that once artists bring cachet to a neighbourhood, and the “interest and value reaches a certain point, the artists are no longer welcome there.”

Samilski also urges the government to re-evaluate and modernize the status of Ontario’s Artists Act, which in its current form, “doesn’t do very much. It sort of acknowledges that artists exist.” Introducing new provisions that allow arts associations like CARFAC to engage in collective bargaining on behalf of the artists presenting at provincial institutions might improve economic conditions for artists. “Wouldn’t it be great if we just didn't have to have these conversations in the first place,” Samilski says.

There’s another hidden cost to shrinking space: it affects the work being produced. Iles says that, naturally, the scale of a studio space dictates the work an artist can create. Plus, adds Schofield, “How do you plan the next six months of your artistic practice if you don't know where you're going to be?” The added stress “becomes prohibitive as a distraction.”

Artists are also becoming more dispersed and scattered across Toronto. While that can have some benefits, bringing creative energy to more parts of the city, it also makes it harder, as Iles says, to “find the community, because you're kind of working in isolation.” Shabnam Ghazi, another artist featured in DECADE, agrees that the geographic dispersal of the artmaking community limits opportunities to connect. “An artist's network and connections within the art community can sometimes influence finding affordable studio space,” she says. “Those with stronger connections may have access to more affordable or shared spaces.”

Before the pandemic, Schofield and Iles remember having no trouble gathering the 12 members of their former artist collective in their studio. Now there are too many barriers to showing up, such as people having to travel further. “It’s stressing the idea of creating a venture in the city with a collective of people, it makes it a little more of a challenge,” says Schofield. “Maybe that's sort of the evolution of the city. But I wish that it wasn’t an afterthought, and that culture was a forethought.”