On Tone: Translating the Vibe of a Room

The blue you see is not the same blue that I see; I hear you differently than you want to be heard; my nose, my room, my furniture, my language is not the same as yours.

Translation begins in a room. Over the summer, this sentence began to loom above my thinking like a mood, or a method. I was co-translating an essay about the filmmaker Chris Marker and arranging books into piles around my apartment. I was sending WhatsApp messages to Katie, my friend and co-translator, about love and parasites. I was also reading Tone, a collaborative experiment written by Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno, where I eventually came across a proposition, or provocation, that felt to me like an alternative translation: “A tone is perhaps a room that we inhabit and are inhabited by.”

Tone is a book that began in friendship, with emails lovingly dashed between Samatar and Zambreno about their concurrent re-reading of Quicksand by Nella Larsen, and soon transitioned to a shared Google document charting their readings, their body feelings, the weather: “Reading the collective animal of the novels we loved, that we wanted to read and reread together. What was it we were hearing? What was it we were feeling?”

They sought to touch tone, a word frequently invoked in discussions of literature but which nonetheless eludes meaning: “We were fascinated by the difficulty of describing this space.” In the book, they introduce themselves as the Committee to Investigate Atmosphere, justifying the committee’s formation by the collective, atmospheric quality of tone: “The study of tone, it seemed to us, was a project that could not be undertaken alone. What creates the vibe of a room? The other people inside it. […] How far is it possible to analyze a fading perfume?”

Tone begins with an abstract, keywords, and a significance statement, all of which joyously thwart the academic constraints of these categories. The Committee’s abstract is perhaps one of the few of its kind to welcome abstraction. It reads like a poem—“We began with a sound”—that is braided with desires, lit from within, and knotted by a rhyme: “We began with this body, which was a collective reading body, the zone of our mutual sensitivity, our ground.” The keywords that follow are another sort of poem, a torrent of mood: “Affect, ecology, collectivity, vibration, architecture / Fog, dust, rot, snow, light / Distance, echo, pressure, gesture, blur”—and a significance statement that undoes itself: “We are still unsure, at the present time, whether we can make the statement for any significance.”

In the chapters that follow, the Committee moves through various inquiries into tone. To my delight, books in translation form a large part of their corpus, and with good reason: the two words—tone and translation—are frequently made to rub against each other. The Committee reads WG Sebald’s Rings of Saturn in Michael Hulse’s translation and understands the reading of a translated novel as “something like a communication of voices. Just as we struggle together, in one document, the translator attempts to sound like the original, attempts to listen to something like a strange cadence.”

A literary translator is frequently asked how she has sought to preserve the tone of her author; or, has she chosen to translate that book because she appreciated its tone? In book reviews, a translation’s tone is as frequently complimented as it is criticized, and most often, little more about the translation is said. We all know what we mean by tone, right? This is why the Committee’s intervention is so vital: they are starting from scratch; and they are starting by scratching, rubbing, relating, touching, tending. They are reading and repeating: the blue you see is not the same blue that I see; I hear you differently than you want to be heard; my nose, my room, my furniture, my language is not the same as yours.

*

A book is a room, too. The rehearsal room that the Committee to Investigate Atmosphere fills is packed, accumulative, a party that’s almost too loud but not quite, electric with the friction of rubbed hands and different voices—literary translators, writers, critics, friends—talking at once: Dionne Brand, Etel Adnan, Saidiya Hartman, Fred Moten, Stefano Harney, Lauren Berlant, Sianne Ngai, Margaret Jull Costa, Maria Judite de Carvalho, Christina Sharpe, Wayne Koestenbaum, Dodie Bellamy, Heike Geissler, Katy Derbyshire, Mary Gaitskill, Polly Barton, Mieko Kanai, Clarice Lispector, Katrina Dodson. This is an incomplete list: a randomly pooled raindrop fallen from a cloud. The book is 115 pages.

The frequent cataloging of the Committee’s materiality—the time that has passed since they’ve met, the paperback books sprawled on their floor, the couches on which they are writing, their hunger—encourage one to look up and around one’s room. The Committee cites Bhanu Khapil at the end of a passage tracking their reading of Humanimal: “We sniff the book cautiously. [...] We think it smells fine. We think it’s all right to read this book at the table. We read, ‘Reaching and touching were the beginning actions.’”

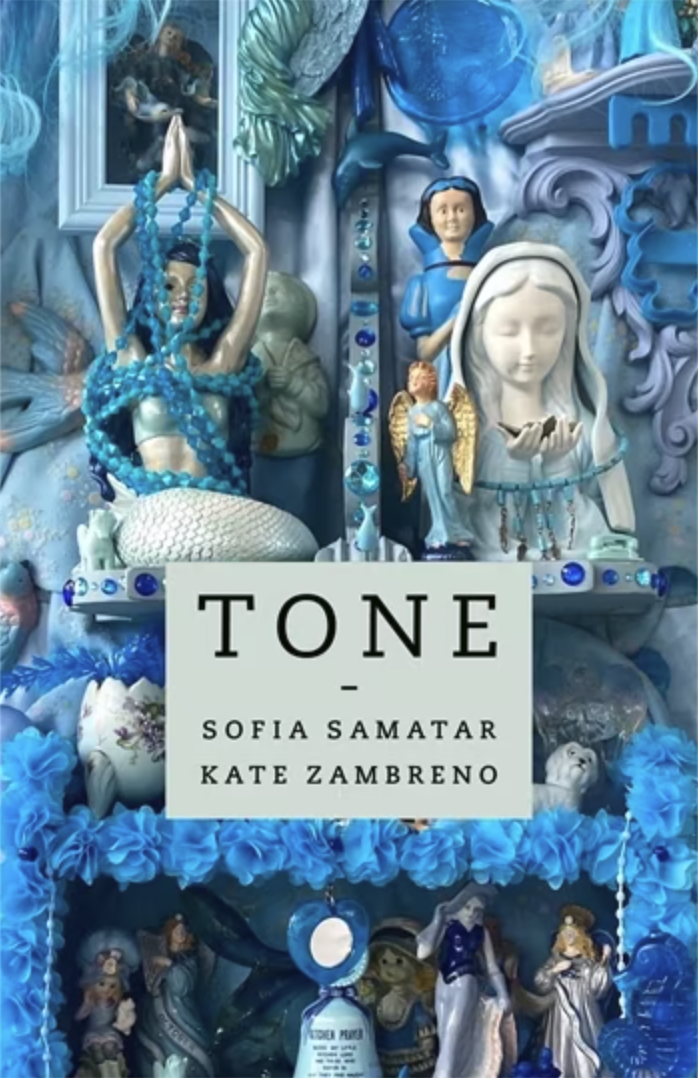

The cover of Tone, featuring a detail of Portia Munson's sculpture Blue Vanity (2022). At right, Munson's Blue Vanity.

Lisa Robertson is not in The Committee’s room, but she is in mine, and I catch her scent throughout Tone. As I read, three white books by Robertson began to form a cloud, an adjacent atmosphere, on my desk—Nilling, Anemones: A Simone Weil Project, and Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft Architecture, the latter of which is also written by “We.” We, or The Office for Soft Architecture—a tonal antecedent to The Committee to Investigate Atmosphere—is the voice that moves through the city of Vancouver, theorizes the weather, witnesses the movements of money, and arrives at this revelation: “An item of furniture is a kind of preposition. ‘By,’ ‘with,’ and ‘of’ are material intuitions.”

In the Committee’s reading of the character Helga Crane in Quicksand, they arrive at a similar conclusion: “The tone of Quicksand is irritating to some readers and energizing to us, but in both cases it is to. Thinking of this, we reflected that though the variations in interpretations of tone may be too great to call it a ‘collective feeling,’ we might at least call it prepositional. Perhaps the study of tone requires attention to positions and how feeling moves between them. Something is radiating, pulsing, attempting to move across.”

*

At the end of the summer, across an ocean, I met my friend Katie for the first time in-person when I visited her in Marseille. Like Samatar and Zambreno, we first met online, in mutual admiration and kindred reading. We kept forgetting that we’d not yet shared a room. Two American midwesterners who found homes in foreign countries, we walked slowly on narrow sidewalks. In Katie’s room, we looked at her books. Before leaving her apartment for dinner each night, she would spritz me with one of her many beautiful perfumes, spread like a shrine across her fireplace.

After I left Katie and went north to Paris, I had an urge to buy myself some perfume. It was my last day, and I liked the idea of returning home to Toronto with a perfume with which to infuse our continued collaboration, to scent our sentences in English. I wanted each of our smells to stain our translation—for our shared document, like Samatar and Zambreno’s, to smell like ourselves and something else.

In the boutique, I texted Katie, embarrassed. I felt conflicted that the words “sweet potato” and “carrot”—orange words that represent foods I care little about—should be written on such a beautiful blue bottle. Even worse, detailed engravings of the two foods were emblazoned on a gold seal. It was the only scent I liked in the room, but the bottle made me cringe. “The nose wants what it wants,” she texted back. And then: “It’s good to have a slightly antagonistic relationship with one’s perfume.”

It’s a response that rhymes with Robertson: “If place is always retrospective, how do we begin? With blatant flaws. Place of cringing.”

And Zambreno and Samatar, citing Fred Moten and Stefan Harney, another collaborative duo: it’s “the irritation of collaboration.”

I bought the bottle. It’s seafoam and gold. It has the words patate douce and sweet-potato on it: a French-to-English translation balm. It looks like it could be placed inside the cover of Tone, which is a detail of a sculpture by Portia Munson called Blue Vanity that is made of “found blue plastic detritus and figurines, fabric, fake hair extensions, and vanity.” I take pleasure reading the last word, which is to be understood as a noun but can’t help being felt like an adjective: vanity—my self, my smell, my garbage, my mood, my insignificance, my extravagance—is included here.

The scent fades fast, but it still gets into my skin, my copy of Tone, and this essay. It furnishes my investigative atmosphere. My next sentence will begin with perfume.