A Stranger in a Town with No Name

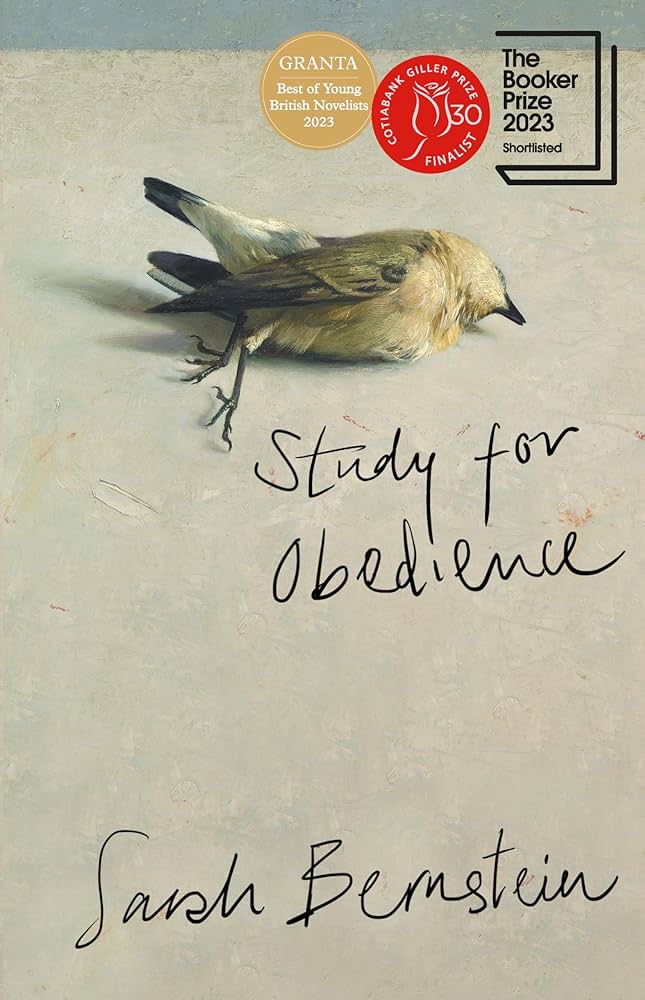

Studies in Obedience, the new Booker-shortlisted novel from Sarah Bernstein, simmers with uneasiness and dread.

A woman arrives in a new town under nebulous circumstances. At first, it seems like she might find belonging amongst the town’s residents. She works hard each day, believing that a strong work ethic will ingratiate her with her new neighbours. Things start going south, slowly at first—a scowl, a turned shoulder in shunning, a reprimand, a stony silence. The town takes on an ominous air that is sure to turn violent.

The above describes Lars von Trier's 2003 film Dogville, starring Nicole Kidman. It also describes the premise of Sarah Bernstein’s novel Study For Obedience.

Shortlisted for both the 2023 Booker and Giller prizes, the Montreal-born Bernstein’s second novel follows a nameless young woman as she moves to an unnamed small town to care for her feeble and recently divorced brother. Things seem off from the outset, though in a way that’s hard to pin down. Her past is sketched out in scenes portraying acts of servitude toward her many siblings. Why does she have so many siblings? Why was she treated as though she is their live-in maid and personal assistant? And why must she bathe her brother, a grown man? The lack of clarity around her situation adds to a mounting sense of unease. Is she being mistreated? Or is it more that she is mistrusted?

In von Trier's films, that sense of unease typically builds to a crescendo of violence, and Dogville is no exception. Watching it feels something like a mosquito bite: you scratch and scrape at the itch until it finally bleeds with relief. The first time I saw Dogville, I paused the film midway, right before I knew the violence was about to occur.

(Photograph of Sarah Bernstein by Alice Meikles.)

No significant harm comes to the protagonist of Bernstein’s novel. I was conditioned to anticipate that something bad was about to befall her, just as it does Grace in Dogville. Instead, Study For Obedience buzzes throughout with low-grade anxiety, the deliberate vagueness of Bernstein’s prose never really making it clear what is going on, as though the book is always several paces ahead of the reader, with too many missing details to fill in the gaps. Meanwhile, the poverty, isolation, bigotry, and superstition that afflict the town only add to the simmering sense of threat. The message is clear: strangers are not welcome. The narrator’s Jewishness in Study for Obedience makes this shunning especially unsettling.

That unsettled feeling is embedded in the structure of Bernstein’s sprawling sentences. She’s a big fan of the comma. Commas interrupt sentences—and the narrators thoughts—constantly. Often enough, at the completion of a sentence the reader is left feeling disoriented, unsure just how it ended up where it did. I frequently had to re-read sentences, as though doubling back on a trail to figure out how I got there.

“I on the other hand had been a dedicated and lifelong smoker, I loved nothing more than a smoke, it’s true, from the age of fourteen I could be found smoking on street corners and doorsteps, in alleyways and in stairwells, and yet I was a stationary smoker, never moved while smoking, hated the sensation of smoking while walking, and I walked plenty—if I had a second, not equal, love, it was walking, I spent entire days walking from one end of the city I lived in to the other and back again, travelling by foot from tram terminus to tram terminus, bus station to bus station, municipal park and industrial park, and back again, always back again.”

The narrator’s digressive train of thought is reflected in how the prose jumps from one clause to another, this frantic interiority at odds with her outward silence. She doesn't speak the language of the people in the town, further ostracizing her from the community. It’s not that the narrator is unreliable; she’s withholding. The novel circles around the drain that is the central conflict, preferring the narrator's inner thoughts.

There is violence in Study for Obedience, but it mostly involves animals: a pig suffocates her piglets; an ewe is found dead with her half-born lamb; a dog has a phantom pregnancy. “That was my problem, I thought, I was always thinking at the level of the individual, in this case the rabbit, the grim scene unfolding before me in the harden as the kite pecked at the belly of the poor beast, initiating a gyration in the corpse or almost the corpse of the rabbit, a kind of organy wobbling,” writes Bernstein. The reader is tempted to interpret all this violence in the natural world as some foreboding for the violence about to befall the protagonist. Instead, she remains steadfast, more of an agent than a victim.

Again and again, she resorts to a ritualistic way of doing things. Lighting the wood-burning stove for heat, despite the house having electrical heat. Cleaning. Volunteering with the township as treasurer. “I found that, perhaps as a result of adhering to the timetables he had created for us, I too came to love orderliness,” Bernstein writes. “The days slowly grew shorter, and I worked to submerge myself once more. Time passed, and I went under.” Domestic work is coded as an avenue to moral purity—the same morality that’s turned on its head and weaponized by the townspeople. In Dogville, Tom is the self-elected mayor of the town’s conscience. Will the townspeople do “the right thing” and accept thy neighbour? Or is protecting themselves and their families the morally responsible thing to do? In Study in Obedience, the townspeople’s choice is clear: she is not welcome. But she won’t leave the town. She claims her right to live.