The Art of Quitting

Maybe true artistic freedom isn’t about about perseverance, but knowing exactly when to stop. Jowita Bydlowska reflects on the decision by her mentor and friend Barbara Gowdy to quit writing.

When Barbara Gowdy quit writing novels and short stories six years ago it rattled me. Nowadays I consider Barbara my mentor and friend, but back then I was a superfan, even a bit of a stan—the kind who would wait outside a bookstore on release day for her next novel. Except there would be no next novel.

As Barbara’s friend, I respect her choice and am even impressed by it. It takes guts to quit—especially when your career appears to be thriving, when your last novel (Little Sister) was a critical success, earning raves from the Canadian press, a BBC “Must Read” selection, a gushing assessment in the New York Times (which called the book “unforgettable,” praising her “electric style and vision”), and a starred Kirkus review. It takes guts to walk away when people are expecting your next hit, to disappoint them so deliberately. It’s a lot more brave than quitting before you succeed, perhaps spending the rest of your life telling yourself that it was just the circumstances and not you. The reality of any artistic pursuit is unglamorous: it demands time, discipline, and an often excruciating patience. The truth is that most starting artists want to launch, publish, promote; they don’t necessarily want the unglamorous parts.

As a superfan, I was angry at Barbara for deciding to rob us of her brilliance prematurely, unlike her friend Margaret Atwood, who had once told Barbara her problem was that she was plagued by perfectionism. Which is also one of Barbara’s reasons for quitting. Her last book took her “ten bloody years to write,” she told me, “six-thousand words a year on average, which is like five-hundred words a month.”

So what? I wanted to yell at Barbara the Author that she didn’t just belong to herself, or that at least her art didn’t. I wanted to remind her that artistic talent is a gift from God, and she is only an instrument of God. I don’t really believe any of that and I’m not Christian but hey—maybe guilt-tripping would work? It wouldn’t. By now we’ve had enough conversations for me to have finally made peace with her quitting. (Plus, I can always reread her books. I’ve read The Romantic three times now, a personal record since I never re-read books.)

As an artist, I envied Barbara’s courage. I constantly think of quitting. Simultaneously, I am obsessed with keeping going. I believe most artists are familiar with this kind of dichotomy. I found Barbara’s quitting inspiring. I could almost imagine the freedom of it: no longer torturing yourself with having to create something better, more perfect than your last work. “I was getting neurotic about sentences,” she once said, “about making them as clear and unadorned as possible.”

But dear god, those sentences. So quiet but hypnotic, trapping you inside the scene that before you know it it’s become your own memory:

“It was like underwater in there, a murky pond. Dark, smoky. Quiet, since it was between stage acts. All around the room, like seaweed in the current, slender, naked women stood on little round tables and slowly writhed for men who sat right underneath them and looked up. The men hardly spoke or even moved except to reach for their drinks or their cigarettes.”

– from We So Seldom Look On Love

“Looking back over his life never came easily to him, and for the sake of avoiding that ordeal – but also because, ultimately, he attached himself to nothing – he’d surrender to anyone’s memories of him. Even mine, these pawed-over resurrections. Even though he knew I loved him too desperately to ever be a reliable witness.”

– from The Romantic

Perhaps knowing when to stop—full stop—is just another part of the artistic process. Sooner or later, we all encounter a wall too high to scale, or realize we have scaled the highest one already. Arthur Rimbaud abandoned poetry at 21. JD Salinger, Ralph Ellison, and Harper Lee never published a second novel (though the latter two had unfinished second novels published posthumously). Marcel Duchamp vanished from the art scene in the middle of his career, largely to play chess. The musician Gotye disappeared after his one massive hit. And who knows how many less well-known, brilliantly talented artists have quit along the way?

Maybe that’s where true artistic freedom lies, not in the relentless drive to keep going, but in the act of stepping back when the moment is right. Paradoxically, perseverance can itself sometimes feel like a form of retreat—continuing, not for the love of the work, but out of a need to avoid confronting something uglier: the fear of being irrelevant, of fading away. Barbara had enormous success with her 1992 short story collection We So Seldom Look on Love and her novel The White Bone from 1998, but for all the glowing reviews of Little Sister in 2017 it did not sell well. “I was tired of being interviewed, and tired of the book club thing. You know, you’re not even sure if they read the book, and if they don't like it you can sort of tell.” It wasn’t quite rejection, more like indifference, which is perhaps even more devastating.

And yet: what do writers do when they no longer write? I realize many go into teaching or PR or apply to law school, but the thought of doing anything else but writing makes me panic. I count my blessings that I’m able to work almost every day, no writer’s block here. I love the struggle and all the unglamorous parts—the writing itself basically—more than the joy of seeing my work out in the world. So I think I was meant to do this; or maybe it’s that I don’t know how to do anything else. Still, I must acknowledge that summer long ago when I ruined my family’s holiday, by sprinting back and forth to a local internet café three times a day, to check for an email I was expecting from my agent. This while my partner wrangled our demanding five-year-old. I regret it deeply, especially since our family split up a year later and that time together became even more precious.

Barbara wrestled with a similar tension. In order to write, for years she would keep family and friends at bay. “I no longer wanted to do that, especially as my older sister and brother have serious health problems,” she told me. “It was time for me to be there for them. In fact, it was time for me to be there for everybody who might benefit from my attention.”

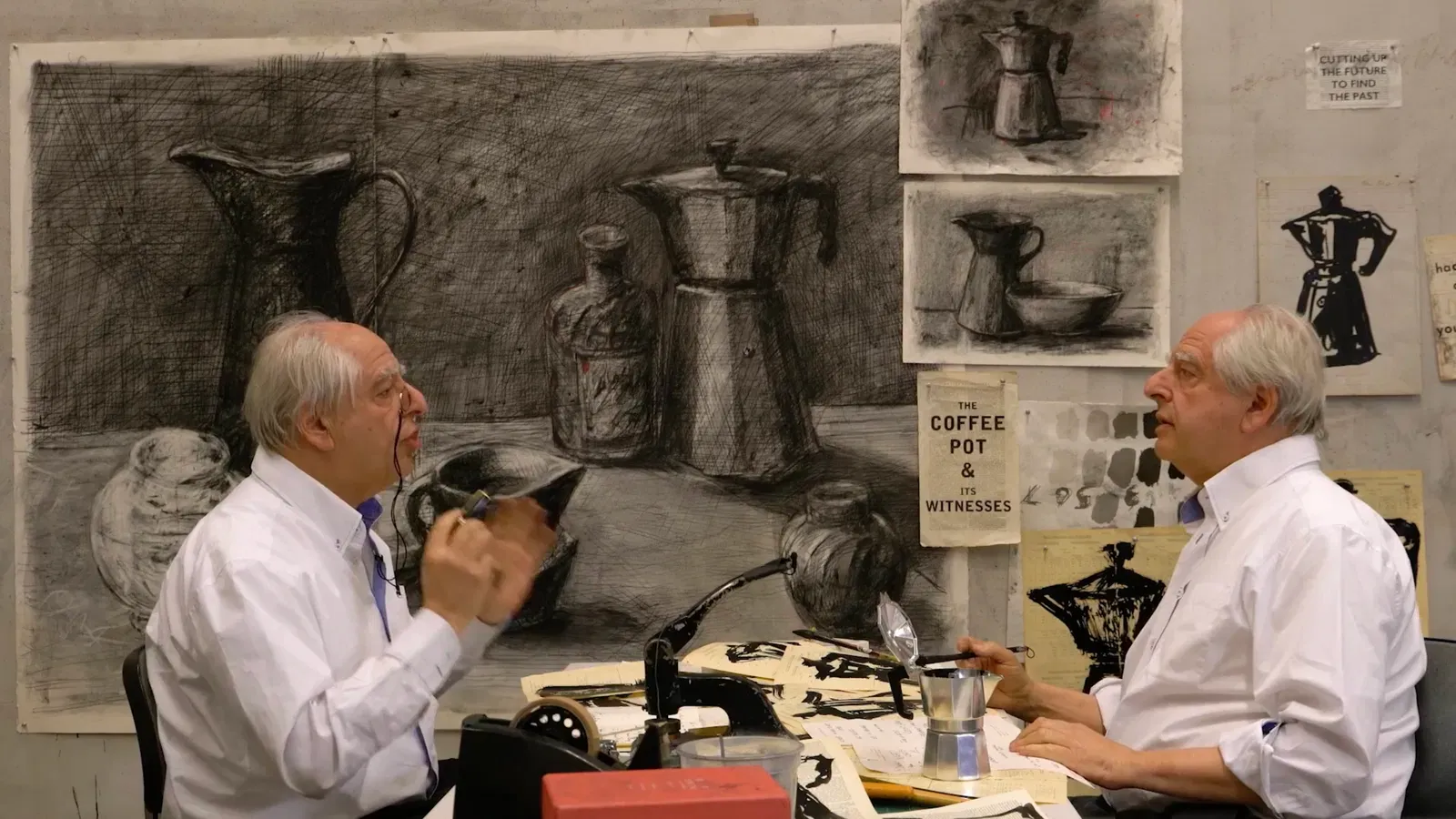

When we met to talk about her decision to quit, it was a struggle at times to stay on topic—being friends, Barbara digressed quite easily into the many other goings on that now consume her life. Her ailing cat, her siblings, their partners and children, as well the newly immigrated family she has taken under her wing, classically trained musicians from Eastern Europe—all needed her help and she gave it. I kept thinking there’s no way I would be able to write even a sentence had I committed to helping that many people.

But herein lies the good old Art vs. Life debate, and the impossibility of committing to both equally. The subject has been dissected enough, especially through the lens of the Woman Artist, a dilemma that often invokes the likes of Tracey Emin or Marina Abramović, who have both said that having families would have been detrimental to their art.

Personally, starting my own family has fuelled my creativity, it’s what gave me discipline and taught me about time. But I often wonder how present I am with my son when I’m deep in my work, living in some other realm. A close friend recently said that when she spends time with me, it sometimes seems like I’m watching a TV show on the other side of my eyeballs. (She’s not wrong.) And, of course, there’s the usual guilt: for not getting a real job, for not being successful enough at what I do to justify all the sacrifices, financial or otherwise. I think about going to law school more often than I care to admit, especially when I see my royalty checks.

Barbara’s third reason for quitting is the only one I’m not sure about. “As an older white woman, I felt I’d had my day—it was time for different voices.” While I appreciate the generosity behind such a sentiment, I would hope there’s room for all of us—especially now, when the degradation of language and thought have become so routine; we need a voice like hers more than ever. Every day, social media impels us to respond instantly (“What’s on your mind today?”), to re-package ideas into slogans and catch-phrases, to measure worth by clicks and likes. Newsfeeds favour the loudest voices, not the most thoughtful ones. Algorithms reward certainty and outrage, not doubt or deep thinking. That’s not even to mention the Trump Administration’s very real attempts to exorcise particular words themselves from the language, or invert their meanings.

In this environment, it’s rare to see a writer rewarded for choosing complexity, for thinking slowly, writing carefully, imagining deeply. So maybe Barbara’s onto something by calling it quits just as the world hurtles toward oblivion. But I don’t think that’s where her words will end up. Because quitting is one thing; silence is another. Writers like Barbara—who can distill vast truths into spare, unadorned sentences—remind us that words still hold power, and that using them is a responsibility.

Fortunately, an artist’s decision to quit doesn’t erase their art. Barbara’s influence will outlast any final page. Maybe the real lesson is that quitting, in some small way, can be a form of living fully. After all, it started with living. Art begins when you take something from the world and give it back in the form of something that lasts. That’s when you realize: there is no real end. There’s only the work—and the way it keeps speaking long after you’ve stopped.