The Boring Kind of Heartbreak

In No Fault, Haley Mlotek searches for the language of love’s quiet undoing—from grief to the unexpected grace that comes with choosing to leave a marriage. Patrick Pittman traces what happens when cultural expectations, legal reform, and literary form converge in the finality of divorce.

“What are the terms that must be met in order to write about one’s divorce with beauty and respect?”, Haley Mlotek asks about halfway through No Fault, her sort-of “memoir of romance and divorce.” That’s what the cover promises, though it might be better read as a collection of essays only tangentially related to the topic, stitched together with just enough memoir to meet the legal definition, possibly written by somebody who really doesn’t want to write one. I don’t entirely mean that as a criticism.

Mlotek’s question is one all of us divorced writers have spent too much time pondering—especially, as in my case, when both participants happen to be writers. The answer depends a lot on the kind of divorce we’re talking about. What I share with Mlotek, other than being a relatively privileged, Toronto-adjacent person of a certain age and scene, is the further privilege of having had a divorce that everyone not directly involved would probably call boring. No children. No wild affairs. Just that shift in circumstance when something you thought would be forever, making very public promises to that effect, is reconfigured into something else—you’re a divorcee now.

The traumas of such a divorce are low key—more sadness than terror or rage. I can say unequivocally that in my case (at least from several years remove) divorce was the better option for both parties, leading to a deeper, more enduring friendship with my ex-wife than would ever been possible were we forced to either remain within a construct that no longer fit, or forced to lie our way through a combative legal system just to find a way out.

“Divorce was the subject that chose me,” writes Mlotek, a multi-generational heir to the topic—her parents divorced, her grandparents too; her mother works as a divorce councillor. “Right inside it was everything I wanted and feared the most: decisions and choices, isolation and entrapment, loneliness and romance. The terror of wondering what story my life would be was a perfect distraction from wondering why life needed to be a story.”

She married her long-term partner, a relationship that started in her late teens, only when it seemed necessary for acquiring the visa that would allow them to move to the US together. It’s that straight: “I married the man I loved because I needed to. Our visas required it, and we wanted to leave our home and find a new one.” It was a relationship where his promises of love were of forevers, and hers were only of “I don’t know.”

When it unwinds, it’s not explosive, it just sort of happens. She can’t really give a clear reason to her partner, or her friends. It’s just done. There are some arguments that are pieced together over the course of the book, but none that any couple hasn’t had, even if she attempts to frame them dramatically. It’s more that the version of her that begins to take hold in New York, that she is ready to grow into, is not the version that married him. This life can’t hold that one. That she can’t entirely put words to it isn’t exactly a fault—that’s just how relationships wind down, more often than we talk about.

A divorce such as Mlotek’s or mine is a very contemporary privilege. To mutually unmake the ’til death promise, and for the world not to end, is the rather dull culmination of so many dramatic battles, and much sacrifice. We can thank feminism, both in its radical and more mainstream iterations, for winning us the legal right to enact the most mundane of endings. In some jurisdictions, like Australia, where me and my ex were married, you can even do the whole thing online. During one of her visits to Toronto during Covid, we had our affidavit witnessed by a moonlighting Canada Revenue Agency lawyer doing legal work from a desk in her backyard witnessed, and then scanned and added to our cart. We later hit the checkout button over a flaky cell connection while camping together on Lake Huron. It was less dramatic than what we’d originally planned—throwing our rings into an Icelandic volcano crater. Unfortunately, we’d messed up the paperwork that time so it had to wait.

How we got to this quietly radical status quo appears to be the starting point for the book Mlotek appears to have set out intending to write—a blend of personal memoir and light history describing how accessible no-fault divorce has helped to reframe the family unit less as a cage than a choice. It wasn’t so long ago in America that a married couple was legally considered a single person—the husband. And so, even before no-fault laws became commonplace, people still found ways. “Strict laws didn’t stop divorces; couples just learned what to say to judges. Marriages ended, and perjury flourished.”

Unfortunately, it’s when Mlotek is wading through the historical material that the book feels unduly dispassionate—as though these are the parts an agent or editor has encouraged her to write, because it’s what readers have come to expect from such books. Too often it feels like Mlotek is dutifully digging through old scholarly articles, and less literary histories of divorce, for the purpose of writing a term paper.

Much more interesting, because you get the sense she cared more about writing them, are the lightly disguised essays forming the bulk of the book’s middle section. Here Mlotek downshifts into a meandering but delicate treatise on divorce, as represented in movies and literature, through the work of Deborah Levy, Grace Paley, Elizabeth Gilbert, Rachel Cusk, Nora Ephron, and others.

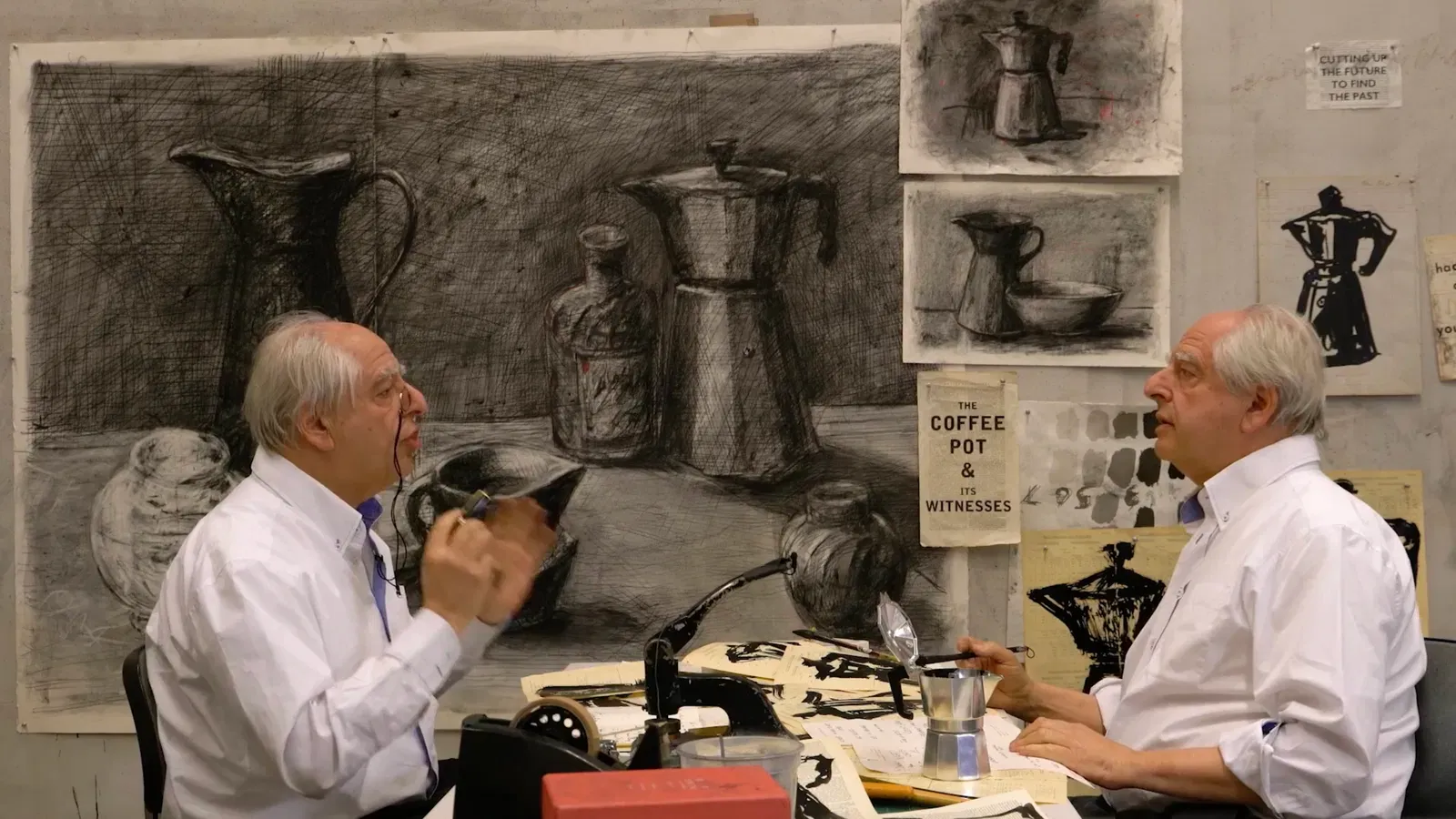

Mlotek is a great cultural critic, and though some of these chapters might feel tenuous, honestly I’d rather read her writing with levity and passion about Ephron than some of the more rote-seeming sections of the book. (The version of No Fault that was purely an essay collection might well have been stronger in the end; I don’t think I’m crazy to faintly sense the voice of an agent telling a writer that nobody buys essay collections wafting in the air.) One section that stands out is Mlotek’s reconsideration of The Continuing Story of Carel and Ferd, Arthur Ginsberg’s art installation/five-year-long film on the performative, very queer marriage of Carel Rowe and Ferd Eggan. A relationship which writer Gary Indiana, a key presence in their story, described as a “vague project that soon became an endless documentary”—a loose prototype of what would follow later in reality television.

Mlotek’s love of romantic comedies also injects life into the middle section. This was the part I was in the middle of reading when, wandering down Bloor Street in Toronto, I saw the marquee of the Paradise Theatre advertising “The Divorced Women’s Film Festival w/ Haley Mlotek.” It occurred to me that maybe this was what she really wanted to be doing, the book an enabler for some exquisitely juxtaposed thoughts on love and marriage as distilled through Cassavetes and Ephron. Perhaps the most fun passage is when she shares the outline of her own hypothetical romcom, spun out of a gig she has stumbled into, writing wedding speeches for rich fathers. Happily, she has already written a treatment, and it deserves to be made into a sharp-witted rom-com of the sort we haven’t seen since Ephron’s peak.

Oddly, while Mlotek writes of seeing the pain in others, whether friends, or characters from books and movies, she doesn’t emit or admit to much pain herself—at least not until the book’s third act, when she begins to show passion and desire for new people. It’s only during her first real breakup after the marriage that a different writer comes to life, where her own feelings come across as something more than just specimens on an autopsy table.

“How could I be falling apart over a man I’d only known for a few months? When my husband had moved out I cried lots, but I cried while functioning. I worked, slept, ate, walked around with friends. In the weeks after Dylan, I passed out at my office and was placed on an emergency sick leave. I couldn’t concentrate on anything and so I couldn’t think; it was like my brain and my body could only be on at separate intervals, and if I tried to use both I would collapse.”

She seems closer to this pain than the one induced by terminating a marriage—what she’s ostensibly writing the book about. Maybe the point is that they’re not separate. When friends express concern over how hard she’s taking the break-up of her short affair, she insists, “they not confuse this with my feelings about my divorce. This sadness, I tried to say, was not about my marriage, was not a sideways form of expressing a grief I wasn’t yet ready to admit. I know what everyone is thinking, I would tell them. I know what people are going to say but they’re wrong, they’re wrong.” One suspects no one was very convinced.

Mlotek freely admits she’s not the sort of person that’s used to sharing this stuff out loud—it’s not her medium of choice. She’s angered when a friend assumes that she must not think about her divorce much, since she rarely talks about it. “I considered my response,” Mlotek writes, “waiting for my heart rate to level before I spoke. Each word came out with a telltale beat: ‘It would be a mistake,’ I said, ‘to consider talking the best indicator of thinking.’”

That’s the bind that No Fault never entirely finds its way out of. So much of it feels like what she was compelled to write because it’s what’s expected of a writer who divorces. If you write fiction, you drip feed it in your novels, but for the non-fiction writer, this is all you’ve got. You struggle to attain the kind of clarity in describing how relationships break or hold that Joan Didion once achieved in a single sentence, that her and John Gregory Dunne were “here on this island in the middle of the Pacific in lieu of filing for divorce.” Mlotek, who quotes that iconic line deep into the book as though she has built towards it, is certainly reaching for something, only it feels closest to her grasp in the sections where it seems like she’s no longer trying so hard to write what she feels she’s supposed to.

“There are three kinds of marriage,” Mlotek writes towards the end. “There is my marriage, which is special: distinct, complex, it defies easy categorization. There is your marriage, which is evidence: of how, as seen by me, your values have served or failed you. Then there is marriage: the category that presumes an ideal exists at all.”

Years ago, when my own short marriage was far from over, but we were in the middle of a bad argument about something or other, I found myself on a crackly phone line talking to Ira Glass for a magazine commission about the lessons that mildly famous people have learned in life. I’m not sure why we turned to marriage, but we did—I asked him about the difference between the commitment we make to a marriage and the commitment we make to any other important, long-term relationship. He told me, I think quoting something he’d said on an episode of This American Life, that it was mostly about time—that the promise you make to each other isn’t that things will be perfect, it’s that you will figure them out over the long haul, that you will make it through the dark patches. What happens, he said, is that you fall in and out of love over and over again.

“You’re right in the middle of the beginning,” he told me.

He was right, but what was beginning wasn’t something that would hold the same shape forever. Time doesn’t always bring you back to the same person—you’re not the same person, and nor are they. Sometimes, things end. Sometimes, new things begin. The lie pushed upon those of us who divorced in this kind of boring, childless way in our twenties and thirties, is that not hanging onto the promise alone is a failure. The promise is to take the time. What you find on the other side doesn’t have to look like what we’ve been told.