The Erotic Landscape of the Bedroom Floor

Linda Besner considers the tangled intimacies laying about in Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie’s The Use of Photography.

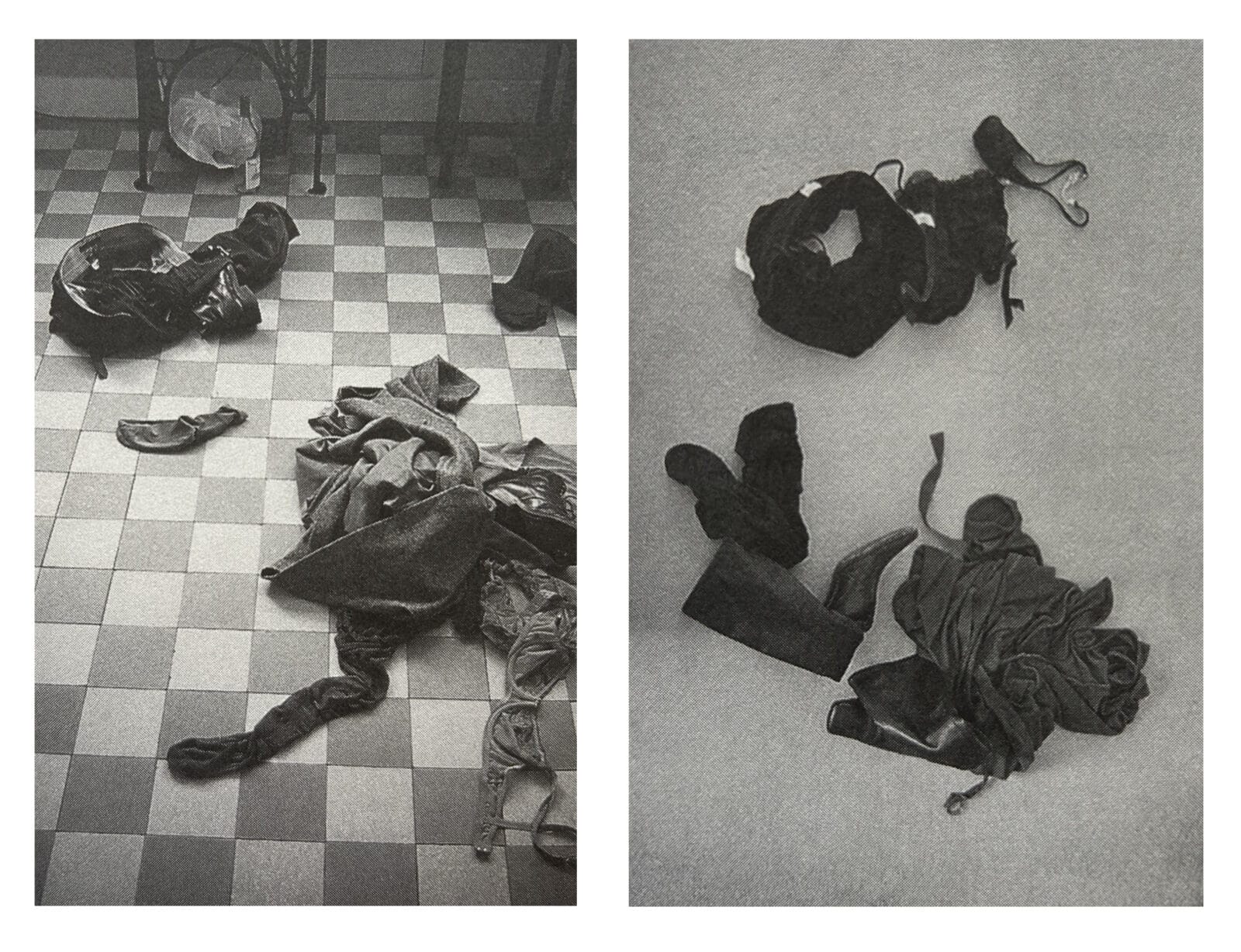

I do not like Annie Ernaux’s shoes as much as I thought I would. I’m disappointed; somehow I thought my appreciation for her aesthetic as a writer would carry over into her wardrobe choices. But the heels in the photograph labelled “at this time in my life” seem to have that squared-off toe I have always disliked, as if someone had mutilated the sole with a chainsaw. I may, however, be doing Ernaux’s fashion sense an injustice. Is it the photo that makes the shoes look ugly? They are small and hard to see, lying in what looks like a basement hallway. The (black?) heels stand like islands in a sea of other detritus: something denim, something cotton. Everything clumps together, looking sodden and unprepossessing.

I have the opportunity to pass judgement on Ernaux’s shoes because the first English translation of her book The Use of Photography, co-written with Marc Marie, was released this year. Published in France in 2005, it tells the story of a love affair. One morning, Ernaux came downstairs and saw a tangle of clothes—torn off in the heat of passion the night before—still lying where they had fallen. “I had a sensation of sorrow and beauty. I thought this arrangement born of desire and accident, doomed to disappear, should be photographed. I went to get my camera.” Over the ensuing months, Ernaux and Marie both took photos of the aftermath of their encounters; eventually, both began to write about the photographs. The book collects fourteen of the photos with their corresponding texts.

“I don’t know what these photos are,” Marie writes. “I know what they embody, but I don’t know what they’re for. I know what they are not: images in frames on a mantelpiece, next to a father, chubby babies and a great-uncle in uniform.”

The photos are not quite art. Ernaux and Marie’s descriptions emphasize the role colour plays in making these compositions beautiful, and the decision to reproduce them in black and white, I think, robs the photos of much of their aesthetic value (the new Fitzcarraldo edition follows the original Gallimard in this respect, but readers eager to see the colour photographs can find them in an edition by Seven Stories Press). Instead, they are personal records, and their “use” from the vantage point of the photographers/subjects is clear—to record a meaningful and fleeting moment. What’s unclear is how to react or respond to them as an exhibit. When we show other people snapshots of our families, lovers, or other records of our intimate lives, what are we asking them to do?

Never mind publishing personal photos in book form or posting them online, some interior designers even warn against decorating the home with family photos. “To us, having too many portraits of yourself on display in your home is kind of like having a tattoo of yourself on your own body. It can come off as vain and tacky,” wrote Sarah Han for the home décor site Apartment Therapy. Utah-based interior designer Shannyn Weiler ignited a storm of TikTok controversy earlier this year when she advised against having so many family pictures that the living room wall ends up feeling like “a shrine.”

This sense that too many personal photos create an unwelcoming or exclusionary atmosphere for visitors may well be at odds with the exhibitors’ intention. Isn’t the desire to show guests the faces of our loved ones a wish to share? But the discomfort designers point to may have more to do with the pressure to generate a socially acceptable response. “What on earth do you say when someone shows you a picture of their husband/ wife?” asks a Reddit user in the r/advice section. It had happened to him three times in the past two months, he added, with random furniture salesmen or other strangers. “They will just kinda pull their phone out and be like ‘that’s my wife’.”

Someone suggested saying, “Wow, yeah they're very pretty/handsome,” or (if this is patently untrue), the more noncomittal, “Oh nice,” with a quick nod. Users of a forum called The Well-trained Mind wanted to know what to say when confronted with unrequested photos of people’s unattractive kids or grandkids. “You can’t go wrong with ‘Oh! Look at those sweet little toes!’” one user suggested. Other options: “He looks like he’s having fun!” “Oh, look at that face!”

“The history of photography,” wrote Susan Sontag in her 1977 classic On Photography, “could be recapitulated as the struggle between two different imperatives: beautification, which comes from the fine arts, and truth-telling, which is measured not only by a notion of value-free truth, a legacy from the sciences, but by a moralized ideal of truth-telling, adapted from nineteenth-century literary models and from the (then) new profession of independent journalism.”

Perhaps the root of the problem is that as viewers, while we understand how to respond to beauty, we don’t have a strong social code for responding to truth. The furniture salesman showing a photo of his wife to a stranger may not be looking for praise for her beauty so much as a witness to her (and his) existence. I love and am loved. I am real. Surrounded by budget sofas and dubious end-tables—public simulations of private, domestic space—the salesman may need to remind himself that he is more than a backdrop for the lives of his customers.

What would a response to the truth-value of a personal snapshot look like? Beauty happens to us; it works upon us. Our response is involuntary, sometimes even against our will. We don’t need it interpreted for us. The kind of beauty that requires interpretation—perhaps we don’t appreciate contemporary dance without prior experience of the art form—is, when we encounter it naively, simply not beautiful for us. It seems false to say that beauty objectively existed in the dance before we were able to perceive it through training. Certain things are beautiful or unbeautiful for us, a perception that may change over time, but which is essentially subjective and neither right nor wrong.

Truth, on the other hand, is not so obliging. It doesn’t necessarily command an instantaneous reaction, and while some things might legitimately be true for me but not for another (that chicken soup makes me feel better or that 10pm is an unreasonably early time for my neighbour to demand quiet), many things are true or untrue regardless of my perceptions. The woman in the picture is married to the furniture salesman whether I believe it or not. Unlike an image accompanying a news story, there is also no clear reason why the fact of the existence of the furniture salesman's wife ought to matter to me.

Ernaux and Marie are likewise uncertain of the function of the photos as public artifacts. They seem to recognize that the viewer has to work harder to engage with them than if the photos were simply beautiful. Ernaux writes: “I cannot define the value or the interest of our undertaking...the highest degree of reality, however, will only be attained if these written photos are transformed into other scenes in the reader’s memory or imagination.”

I would contend that, despite Marie’s assertion, these photos are not qualitatively different from mantelpiece photos. They reference sex, yes, but so do wedding pictures and photos of newborn babies. In terms of their power to shock and disturb, “a great-uncle in uniform” seems to me potentially much more upsetting. (A friend recently suggested that his mother might not want to display his grandparents’ wedding photo in quite such a prominent place; the photo was taken in Germany, and his grandfather is wearing an SS uniform.)

Perhaps the response that best honours the truth-telling function of a photograph is not a statement (“Look at those sweet little toes!”) but a question. Better yet, a series of questions. How long have you been married? How did you meet? Do you see your grandchildren often? Ernaux and Marie proactively fill in this narrative space for the reader/viewer; their reflections on the photographs are what make these artifacts meaningful for the rest of us. For me, the most lasting image in the book is not one we see at all, but one that is only described to us. The couple is on holiday in Venice, and have climbed the bell tower of a 16th-century church much painted by Monet. “I slipped off my bra under my T-shirt,” Ernaux writes, “and threw it into the air, hoping it would fall into the cloister. It hovered for a long time, borne by the breeze in the opposite direction. It was one of the most graceful sights in the world...It is always this image of the bra drifting gently in the air around San Giorgio that comes to mind when I think of that trip to Venice.”

I read The Use of Photography as an attempt to elaborate an emotional landscape between the most clearly “erotic” images of discarded clothes (bras and high heels strewn across the floor in underwear ads), and images that just look like chores to be done (picking up, laundering, folding, putting away). It’s a synecdoche for a very specific type of love affair: neither a one-night stand nor a marriage, it manages to be fleeting without being impersonal, and intimate without carrying too heavy a load of responsibility.

One use to which a viewer can put truth-telling photographs is the purely imaginative: what if that were my wife, my child, my love-affair? The unbeautiful image may shock us out of a comparatively passive receptivity and drive us into deeper engagement. If it isn’t beautiful, perhaps it’s the news, or the newsworthy? Contemplating Ernaux and Marie’s photographs made me think about how the clothes on the floor are briefly free of ownership, left in a communal tangle. We’re seeing a moment when the personal—what is closest to the skin—takes on an existence independent of the person. It’s the hope of every memoirist, and perhaps of every artist. The vision made real, and sent out into the world.