The Incredible, Moveable, 3D Book

From anatomical and astronomical texts to harlequinades and Buck Rogers—book collector Larry Rakow on how a 14th-century invention became a staple of childhood.

Larry Rakow, the founder of Wonderland Books in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, is a bookseller, an avid collector of children’s books, and a historian of their often overlooked history. Formerly a children’s and young adult librarian, Rakow launched Wonderland in 1990, dealing in old, rare, and out-of-print kids’ books.

While moveable books originated in the 14th century, it wasn’t until the 18th century and the arrival of children’s books as its own publishing category that the popularity of pop-ups began to take off. As a result, if you look at the history of kids’ pop-up books as artifacts it very much reflects and tracks with the evolution of popular culture, film, printing technology, and notions of children's autonomy.

“From a flat, almost two-dimensional object, they unfold into three-dimensional volumes, revealing scenographies often architectural in character,” writes Basel-based architect Manuel Herz, whose design for a new commemorative synagogue at Babyn Yar in Kyiv was inspired by the unique world-building properties of kids' pop-up books. (Herz’s synagogue is currently the subject of an exhibition showing at the Koffler Centre for the Arts.) “Who can resist the temptation to open up these books and see how a new and surprising world unfolds? We can get lost in this new world, as in a cabinet of wonders.”

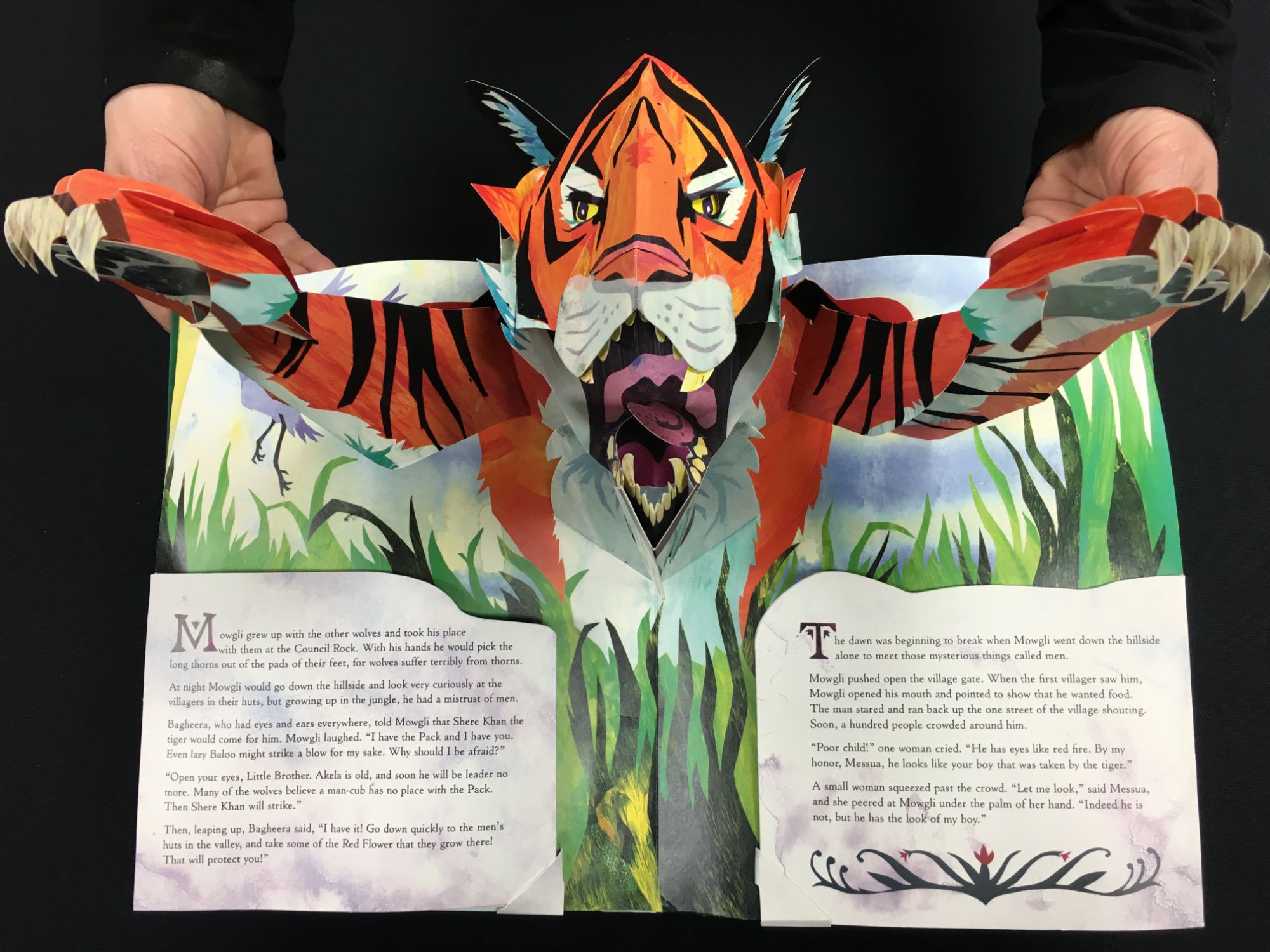

Designed by paper engineers, pop-up books have evolved to become more complicated and intricate as technology has advanced. To keep production costs and book prices low, in recent decades publishers have been outsourcing the labour of hand assembling pop-ups to factory workers in Central America, who are paid very little for what is technical work. Now even these factories are closing, further driving up the costs. The nearly 300-year evolution of childrens’ pop-up books is bound to change again—most likely toward more exclusive and specialized artist editions, as will be the case with moveable books generally.

Below, Rakow takes us on an illustrated trip through the history of moveable children’s books, from the technology’s roots in serious books of anatomy and astronomy, to the first harlequinades and later the pop-ups that most of us would recognize from our childhoods.

+

Larry Rakow: When I was a librarian back in the seventies, my two small children really loved books. Among my responsibilities was reviewing kids’ books to add to our library’s holdings and one day I came across The Haunted House by Jan Pienkowski, which is a great pop-up book. It was really adventurously done, with terrific illustrations. I was sure my kids would love it. So I bought a copy, took it home, and they did—they absolutely adored it to death. Within a week they had torn out all the pop-ups. The entire book was in tatters in no time at all. I thought, that's interesting, I wonder how long these things have been around. And how many of them have survived.

It turns out that children's books especially are hard to collect and preserve over time because, of course, when kids get their hands on them, they do all sorts of things—tear out the pages, colour them, drool on them, any number of things that are fun for kids but horrible if you’re trying to maintain an archive or collection. Pop-up books take it to another level entirely, since you have these incredibly enticing illustrations that move. After seeing how my kids responded to The Haunted House, I started collecting pop-up books and investigating how long they've been around, and where they fit into the larger history of children's books, whether in terms of the art and illustrations or production techniques.

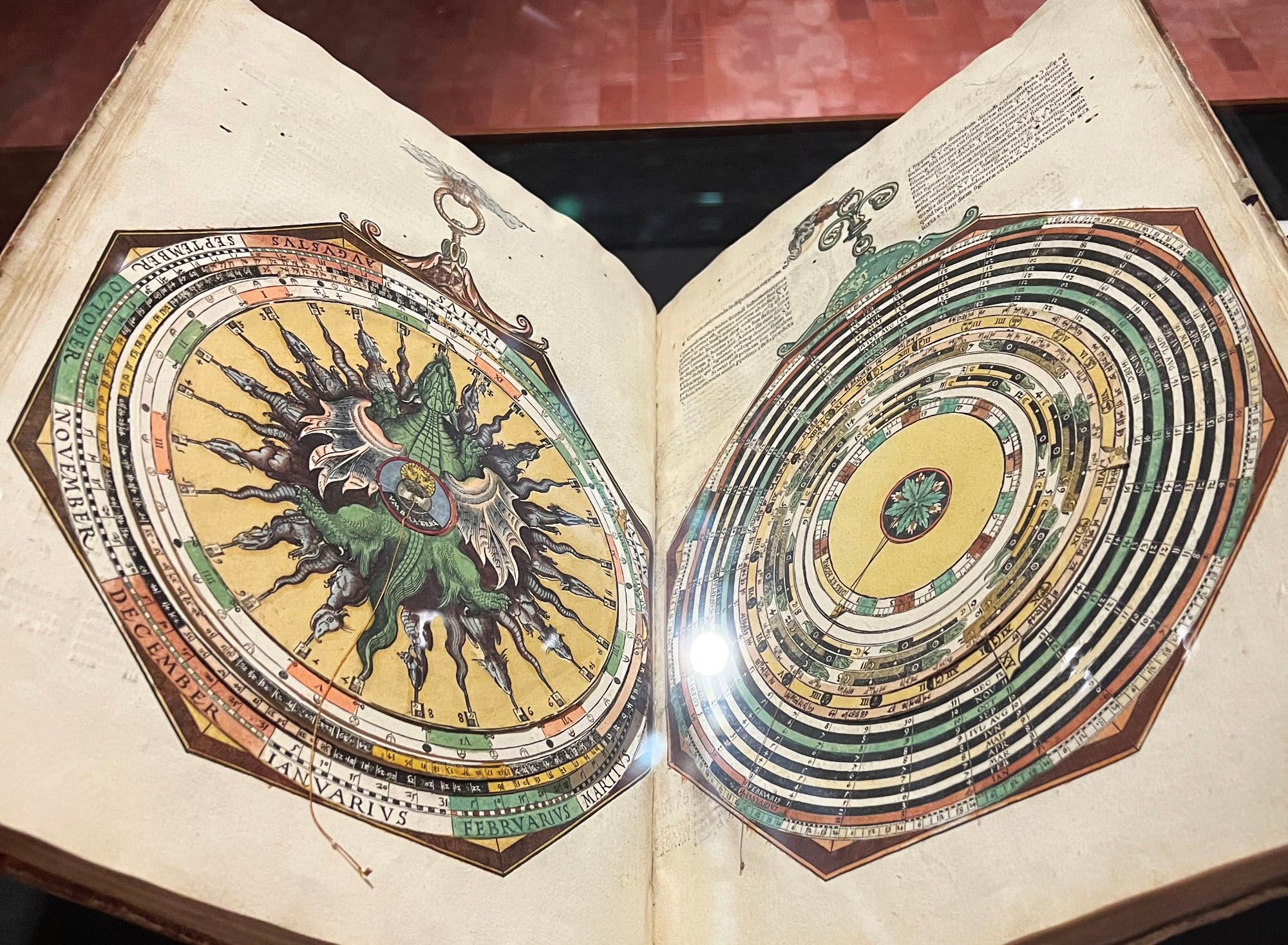

Movable books actually preceded the introduction of children's books by a few hundred years, with the earliest examples coming in the 13th and 14th centuries. Over the first few centuries of their existence, movable books were made for adults, and their subject matter was usually scientific or academic in nature—books about astronomy, astrology, anatomy and other sciences. They often had these circular constructions with layered plates called volvelles, where you would pull on a string or ribbon that would turn to show, for example, when certain constellations would be visible in the sky. A good example of this is the Astronomicum Caesareum (Imperial Astronomy) published in 1540 by Peter Apian and dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor. It was the most intricate book of its time, featuring 22 hand-coloured rotating illustrations (volvelles) that help calculate astronomical and astrological events, including horoscopes. So the technology was understood centuries before the real introduction of children's books. But it’s only then, with kids’ books, that pop-ups take off as a phenomenon.

In the 1760s the English printer Robert Sayer introduced his harlequinades books series, what he called “turn up books”, the precursor to the first pop-ups for children. The stories in the harlequinades were based on the form of theatrical pantomime then popular in England, with stock characters inspired by Italian commedia dell’arte. Basically, when you opened the book to a spread you would have multiple panels telling the story in illustrations and text, with flaps at the top and bottom. Then if you lifted any of the flaps it would reveal another illustration underneath. And that would represent a sequence in the harlequinade. A little later you also started seeing paper dolls take off, which sometimes came in book form. The idea where you can overlay different outfits and such on the doll—a concept that remains popular today.

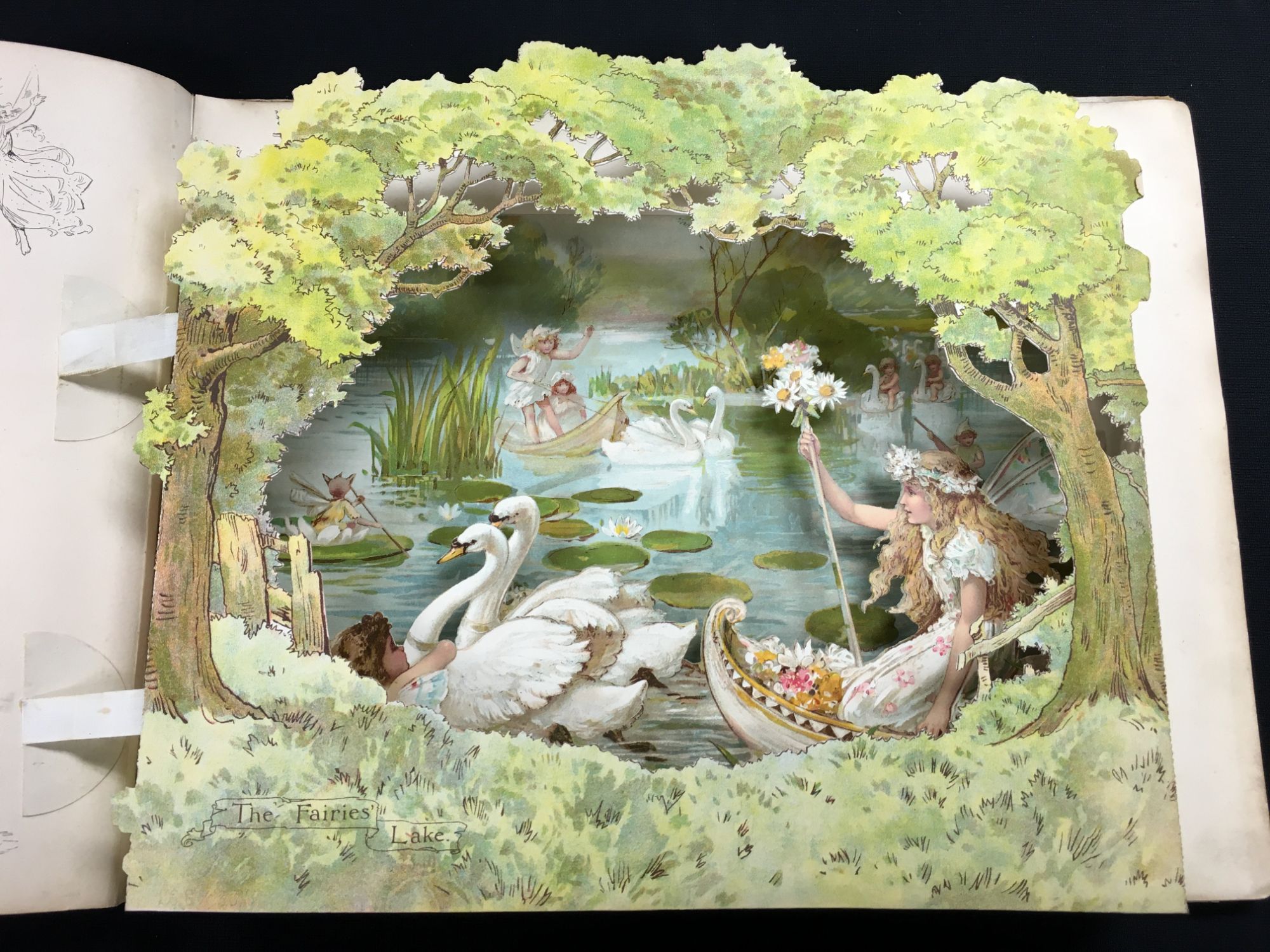

It wasn't really until the mid-nineteenth century that Dean & Son, a publisher in London, introduced the first true pop-up books as we know them today. Their first pop-up retold the Cinderella story, the next one Robinson Crusoe. The art laid flat on the page until you pulled on a ribbon that would activate the pop-up. Soon more pop-up publishers emerged, many of them in England and Germany—in addition to Dean & Son, there were companies like Nister and Father Tuck.

It was a period of innovation for pop-ups as each company experimented with their own technologies and methods. Some used volvelles, which had been around since the earliest pop-ups. Others had these two interlocking frames, and as you pulled on a tab the picture would change. Some operated like Venetian blinds, using slats.

When the German company Nister opened an office in London for the English market, they were able to build a relationship with Dutton, an American publisher. That’s how it happened that many of the first pop-ups to first come out in the United States originated in Germany. Pop-up books were now reaching all over the world, their popularity growing.

The period from 1850 until around 1910 is today regarded as the first golden age of genre. Of all the 19th-century pop-up creators, the most famous and elaborate with his designs was the illustrator and cartoonist Lothar Meggendorfer. He created almost 200 movable books during his career, roughly spanning 1880 to 1910, some of which are still being reproduced today.

With Meggendorfer’s work especially, you see how the technology of movable books, and its evolution, coincided with the first mass-produced versions of magic lanterns, which used hand-painted slides and a mechanism of cranks and levers to create motion on a screen for the first time. Interestingly, the mechanisms used in magic lanterns were the same mechanisms used to activate three-dimensionality in the movable book.

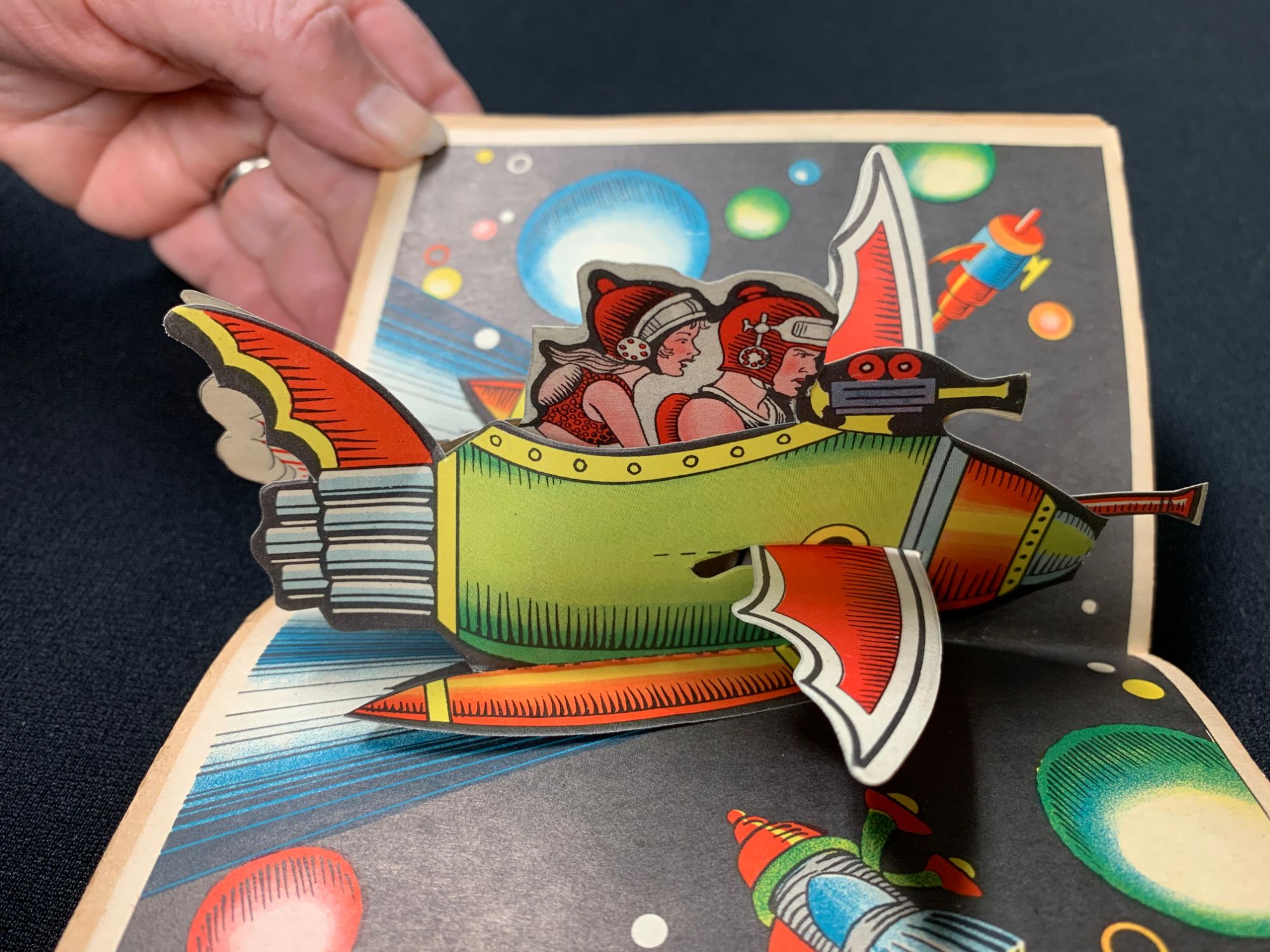

Like any art form, there are peaks and valleys. During the 1900s another period of innovation for movable books was coming to an end and it wasn’t until the 1930s that the next big surge came, much of it thanks to Blue Ribbon Books out of New York. With radio by then in so many homes, you had the beginnings of mass media and what would become popular culture. What Blue Ribbon did was connect the pop-up with that new popular culture, so they were the first ones to do Mickey Mouse pop-up books, Tarzan, Little Orphan Annie. Characters that children would know from the funny papers, radio, and early serials. Those books were tremendously successful. The paper engineer who created most of those was Harold Lentz, and his books are very collectible nowadays. And it’s only then, in the 1930s with Blue Ribbon Books, that we actually started calling them pop-up books—the term came from them.

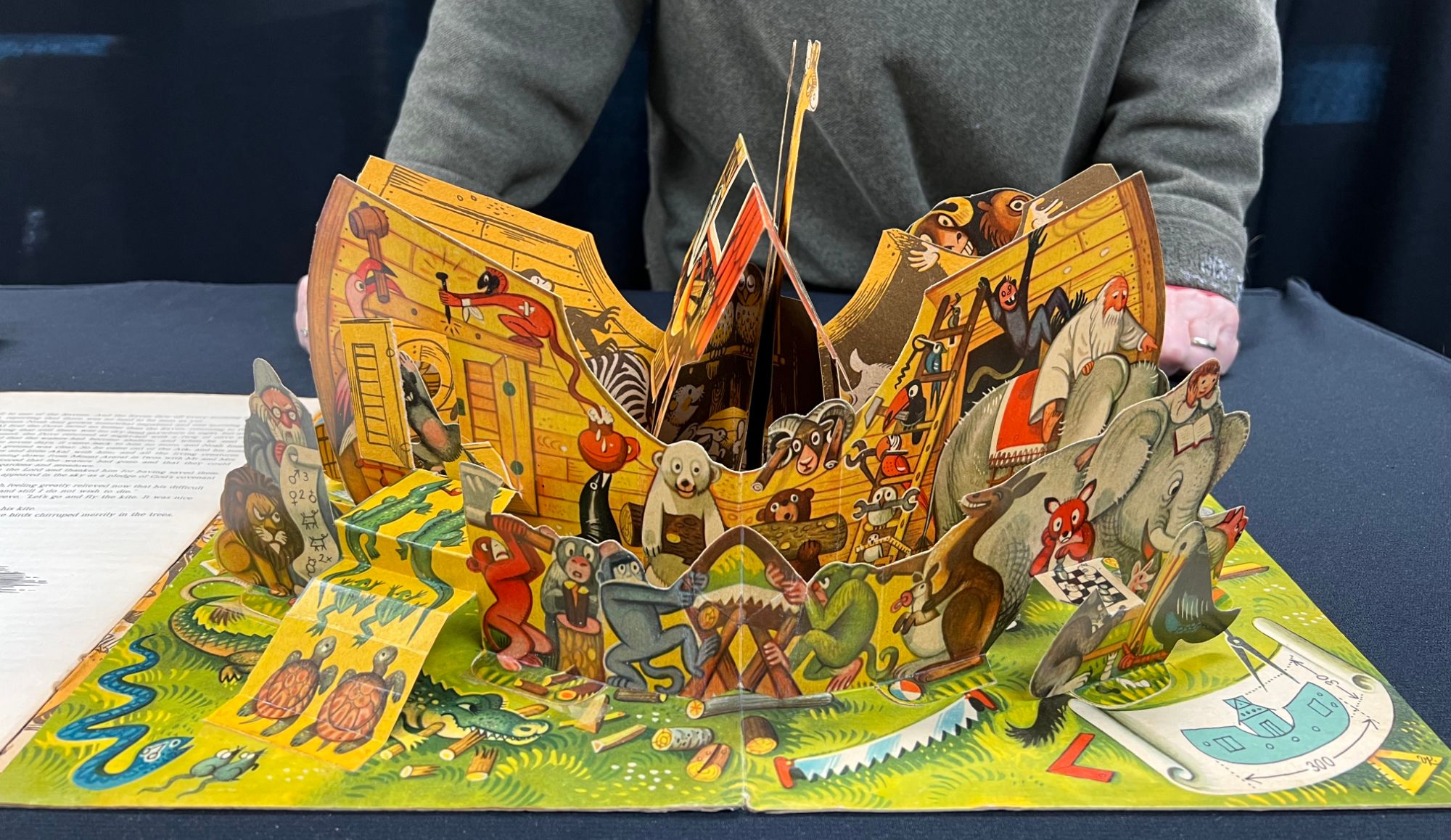

The next big step in the evolution would happen on the other side of the Iron Curtain, in the 1960s, with Vojtech Kubasta’s work in Czechoslovakia. His books are very intriguing because at first they don’t really look like anything special. He published what he called the “Panoscopic Model Series”, which you’d read like any other book, but then hidden inside the back cover there would be this incredibly elaborate pop-up. These are generally regarded now as some of the finest examples of paper engineering around the mid-century. Since Kubasta’s books were published by a state-run company called Artia, people worried whether these books, as wonderful as they were, would escape the Iron Curtain, so they could be appreciated in the West. Fortunately, the books did manage to get out, and were translated into a number of languages.

The one figure who brings the history of pop-ups up to the present day is Waldo Hunt, a collector and publisher who started the company Intervisual Communications in the 1970s. Hunt almost single-handedly revived the market. Not only did he license characters and stories from Disney to create popular new pop-ups, but he resurrected wonderful old titles from Nister and Meggendorfer, introducing them to a whole new audience. Many of these books are still in print today.

Two contemporary pop-up engineers worth noting are Robert Sabuda and Matthew Reinhart, who are absolutely remarkable. They did a whole series called Encyclopedia Mythologica: Gods and Heroes, which has four or five books. Sabuda and Reinhart worked together and collaborated on several projects over the years, but now maintain separate and independent studios.

Unlike regular book publishing today, where the production process is very streamlined and runs in large batches on presses, pop-up books are still hand assembled. Beginning in the 1990s, much of the production for pop-up books moved overseas—first Central America, then Southeast Asia—where labour is more inexpensive. Primarily you have women working at these long tables, applying the glue points, pasting all the elements and making sure they fit, that everything popped up, unpopped up.

Today a book from the Encyclopedia Mythologica is priced at around $19, which is nuts considering the amount of manual labour that goes into it. But as labour prices have risen all over the world the number of pop-ups that are being created, especially extraordinary pop-ups like Mythologica, has fallen off.

While the current golden age of pop-ups feels just about over, in many ways the field still feels wide open. Paper engineering—and it really is engineering—is now being taught in art schools. If you look at a list of the members associated with the Movable Book Society you’ll see that the field is attracting as many women as men. You have artists making their own intricate, handmade, limited edition pop-ups. There’s just something about them that continues to excite the imagination.