The Lonesome Burden of Being a Plant

The question of whether plants could have consciousness has not been left quietly back in the ’70s, as Linda Besner discovers in Zoë Schlanger’s new book, The Light Eaters.

The journalist Zoë Schlanger was interviewing a botanist, and she saved her most contentious question for last. “Could the whole plant be something like a brain?” Schlanger had been worried that the botanist, Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh, would be angry or derisive at this anthropomorphization. Van Volkenburgh smiled. Then she leaned in closer and whispered her response. “‘I think you’re right,’ she said. ‘I just don’t talk about it.’”

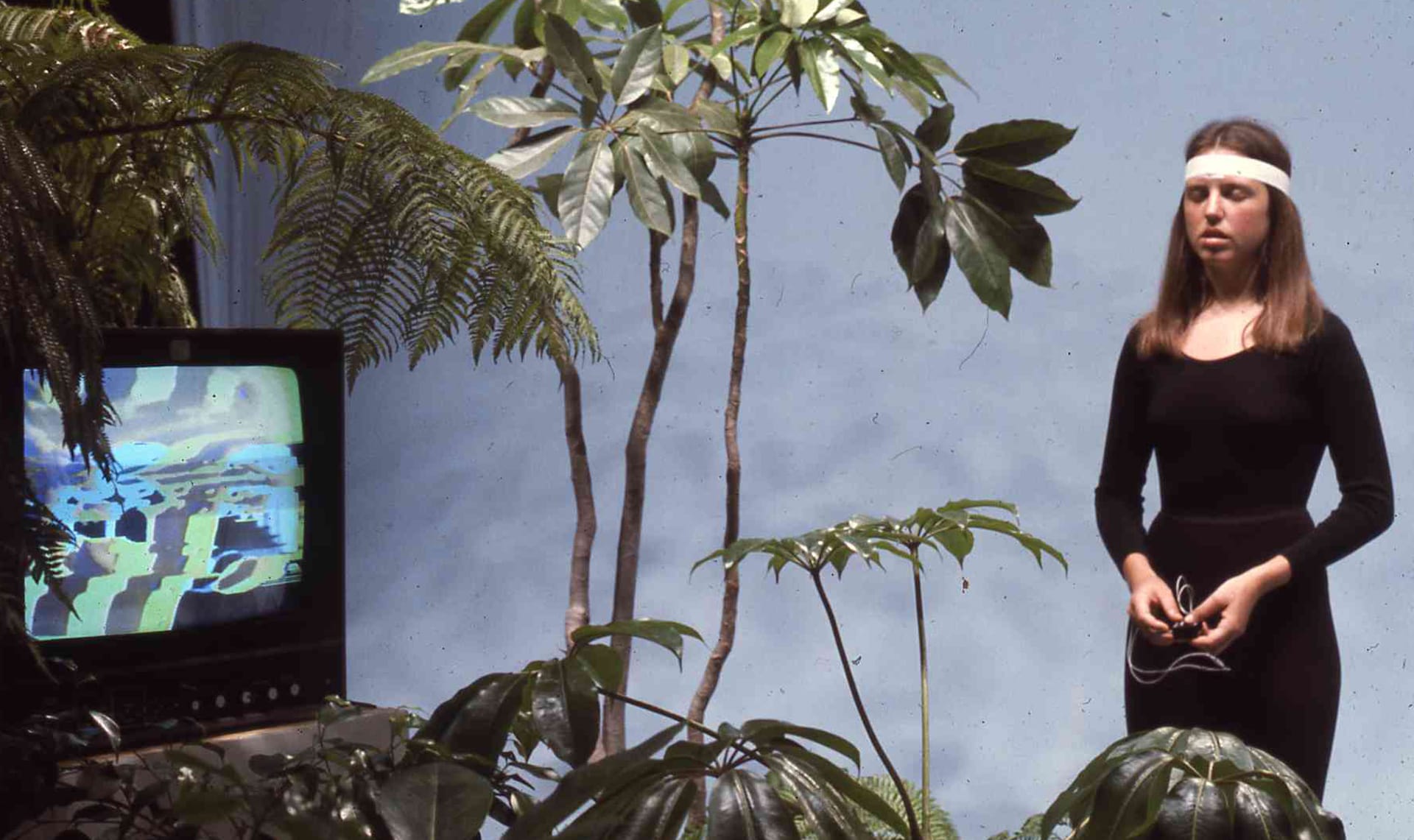

There is a surprising amount of cloak-and-dagger in Schlanger’s new book, The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth. Scientists are reluctant to be caught discussing whether plants are, in some sense, intelligent or conscious beings. In part, this reluctance is due to the long shadow of another book. The Secret Life of Plants, written by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird and published in 1973, made spectacular claims: that plants preferred classical music, applauded their caregivers’ sexual climaxes, and even “might originate in a supramaterial world of cosmic beings which, as fairies, elves, gnomes, sylphs, and a host of other creatures, were a matter of direct vision and experience to clairvoyants among the Celts and other sensitives.”

Fifty years later, some scientists are quietly probing into received notions limiting our understanding of what plants are and what they can do. Schlanger devotes chapters to experiments conducted in the past five or ten years indicating that plants communicate, see, hear, and feel. We might be, Schlanger writes, on the edge of a revolution in how we understand life on this planet.

In terms of our ethics, acknowledging plants as sentient creatures has the potential to seriously disrupt how we think about ourselves. Schlanger looks around her apartment at her tropical houseplants, kept in pots far from their ancestral territory. “Was I now keeping them like animals in cages, confined, muted, in their pots? It was chilling to imagine.” We do not, of course, need to keep houseplants. We do, however, need to eat. Movements like veganism aim for a version of moral life lived outside the systems of domination that pervade our relationship with animals. What does it mean for our systems of morality if human life simply can’t exist on Earth without causing the suffering of other intelligent beings?

In her 1984 book, Ordinary Vices, the political theorist Judith Shklar wrote that if “liberal and humane people” were to assign a ranking to all the possible vices, “intuitively they would choose cruelty as the worst thing we do.”

Yet in a review of philosopher Yi-Fu Tuan’s Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets, published in the London Review of Books in 1985, Shklar makes clear that her concern is human subjects. Tuan suggested that all relationships in which humans exert power over other beings contain elements of cruelty—even our relationships with plants. Topiary, bonsai, and even the simple planting of diverse plant species in gardens where humans dictate where and how much they may grow are breeding grounds for domination. Shklar was having none of it. “It is difficult to understand how anyone, except in this kind of irrational vision, could see a cruel aestheticism in our desire to alter plant growth and the flow of water,” Shklar writes. The case for animals, she concedes, may be different, as family dogs are “feeling, sensitive beings and as such subject to cruelty in a meaningful sense of the term.”

So plants, at least for Shklar, are not “feeling, sensitive beings.” For millennia, the notion that it would be ridiculous to assign value to the kind of life a plant may be said to possess has worked almost as a moral boomerang in Western ethics. Some people, wrote Augustine in the fifth century, try to extend the Biblical commandment not to kill even to animals. “But if so, why not extend it also to the plants,” Augustine argued, “and all that is rooted in and nourished by the earth? For though this class of creatures have no sensation, yet they also are said to live, and consequently they can die; and therefore, if violence be done them, can be killed.” Since he deemed this idea patently ridiculous, he concluded that it must also be ridiculous to imagine that we are forbidden from killing animals. The moral permissibility of hurting plants made it morally permissible to hurt animals, too.

Eastern philosophical traditions, by contrast, as well as Indigenous traditions in the West, may have less difficulty reconciling new scientific knowledge about plants with existing worldviews and practices. Schlanger quotes a passage from Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass in which Kimmerer describes attending an Indigenous gathering after many years of university study in white spaces. The way her elders were speaking about plants as if they were people, discussing their likes and dislikes, was “like smelling salts,” waking her out of a sterile scientific shadowland.

But if plants are more like people than we are given to think, what would it look like to avoid being cruel to them? In this sense, cultures like the Potawatomis’, in which honouring animal spirits does not preclude eating fish, elk, and deer as part of a traditional diet, contrast with a tradition like Jainism, in which the belief that animals have souls underpins a mandatory vegetarianism. Strict ascetic Jains are even supposed to avoid root vegetables like onions and potatoes, since eating the bulb kills the plant. The rationale offered in texts like the Tattvarthasutra for eating plants at all rests on a hierarchical division into more or less “evolved” forms of life. Hurting “five-sensed” animals—humans, tigers, cows—matters more than hurting “lesser-sensed” beings like insects, which in turn matters more than hurting “single-sensed” beings like plants.

If we accept that plants also have something resembling our definition of “senses,” as well as exhibiting patterns we might call “behaviour,” agriculture as it is largely currently practiced starts to look much more like factory farming. And it may seem as though the answer would be a return to a less interventionist relationship with nature—a move away from domestication and towards respecting life where and how it occurs in the wild.

One of the most interesting propositions in Schlanger’s book, however, is that plants are not, or at least not always, passive victims in their relationships with us. In the course of inquiry into how plants relate to insects and other animals, botanists have found that these relationships are symbiotic—both parties benefit. The larger partner is the host; the smaller is termed the symbiont. “A fleet of humans carefully tending a field of crops can certainly start to look like an army of plant symbionts, diligently serving the plants’ needs,” Schlanger writes. When she interviews the Slovakian botanist František Baluška, he comments: “I think the plants are primary organisms, and we are the secondary ones. We are fully dependent on them. Without them, we would not be able to survive. The opposite situation would not be so drastic for them.” When we need plants so much more than they need us, who can really be said to hold the most power?

Reading Schlanger’s book, I wondered: do plants know we are alive? Do animals? If humans have been wandering the planet lonely as a cloud for all these years, thinking themselves the only specks of intelligent life in the cosmos, it would seem to follow that plants and animals may be thinking the same. Perhaps plants see the two-legged creatures swarming around them making unintelligible noises as just so many empty containers, alive in a mechanical sense but incapable of what a plant understands as real consciousness. Programmed, at best, to pursue a series of actions, but without the ability to ask themselves why.

Do plants chafe under the lonesome burden of consciousness? Every morning, I sit on my front balcony with my coffee and look out at a maple tree and a honey locust growing in the public verge of the sidewalk. I’ve named them Giselle and Sweet Jesus, on the theory that since we spend so much time together, I ought to acknowledge their individuality in some formal way. Perhaps they have also given me a name in the same vein of slightly mournful fancifulness, as if to pretend I could ever form a real part of their community. As if I were someone they could truly know.