The Naked Pool

At the intersection of the public and private, the clothed and unclothed, the swimming pool has long been a favoured motif among artists and writers. But as fall settles in, what about the months when it's closed? Who are the artists of the drained pool?

Someone has left a blue towel behind.

It’s draped over the railing of the closed swimming pool in Toronto’s Monarch Park, rumpled up on one side, flanked by concrete planters of brown nasturtiums and tattered marigolds. Only one other sign of pool life remains: a pair of rubber flippers poised at the edge of the deep end, turned neatly upside down, the water long since drained from the inverted ankles.

A few short weeks ago, this was my paradise: a dazzling jigsaw of sun and shade, blue and white, the human and the elemental. Now, I’m looking at the swimming pool from the wrong side of a chain link fence. It’s a greyish September day, the tang of chlorine intermittent on the chilly wind. The doors to the change rooms are locked. Soon, the pool will be not only unpeopled, but empty of water. Drained for the season.

The sensual appeal of the swimming pool—as an intersection of the public and the private, the clothed and unclothed—has made it a favourite motif for artists, in both literary and visual forms. Think David Hockney’s eternal Californian summer in A Bigger Splash, or the privileged and gin-soaked Winchester County of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer”. Even with no bodies in sight, the pool performs a seduction, in the way its rigid lines and right angles are subverted by the reflective surface, throwing back squiggled railings and shards of light.

But there is a brief moment—between the day or hour when the pool is emptied and the moment when it is covered over for the winter—in which the waterless cavern stares back at us with a dry eye. Who are the artists of the drained swimming pool? Once emptied of the substance that provides it with surface meaning, what harsh profundities might be found at the bottom of its bare form?

*

In 1984, an interviewer for the Paris Review asked the British novelist and short story writer J.G. Ballard why he so often returned to images of abandoned hotels and emptied swimming pools. “Ah, drained swimming pools! There's a mystery I never want to penetrate,” Ballard responded. His father had worked for the Shanghai division of a printing company, and Ballard was a child when, in 1937, Japan invaded, and his family took refuge in a house in the French concession. The house had an empty swimming pool in its garden. “It must have been the first drained swimming pool I had seen, and it struck me as strangely significant in a way I have never fully grasped,” Ballard wrote in his 2008 memoir, Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: An Autobiography. “I was unaware of the obvious symbolism that British power was ebbing away.” Swimming pools with no water in them, he told the interviewer, strike him as “psychic zero stations.” Like the Go square in Monopoly, a reset.

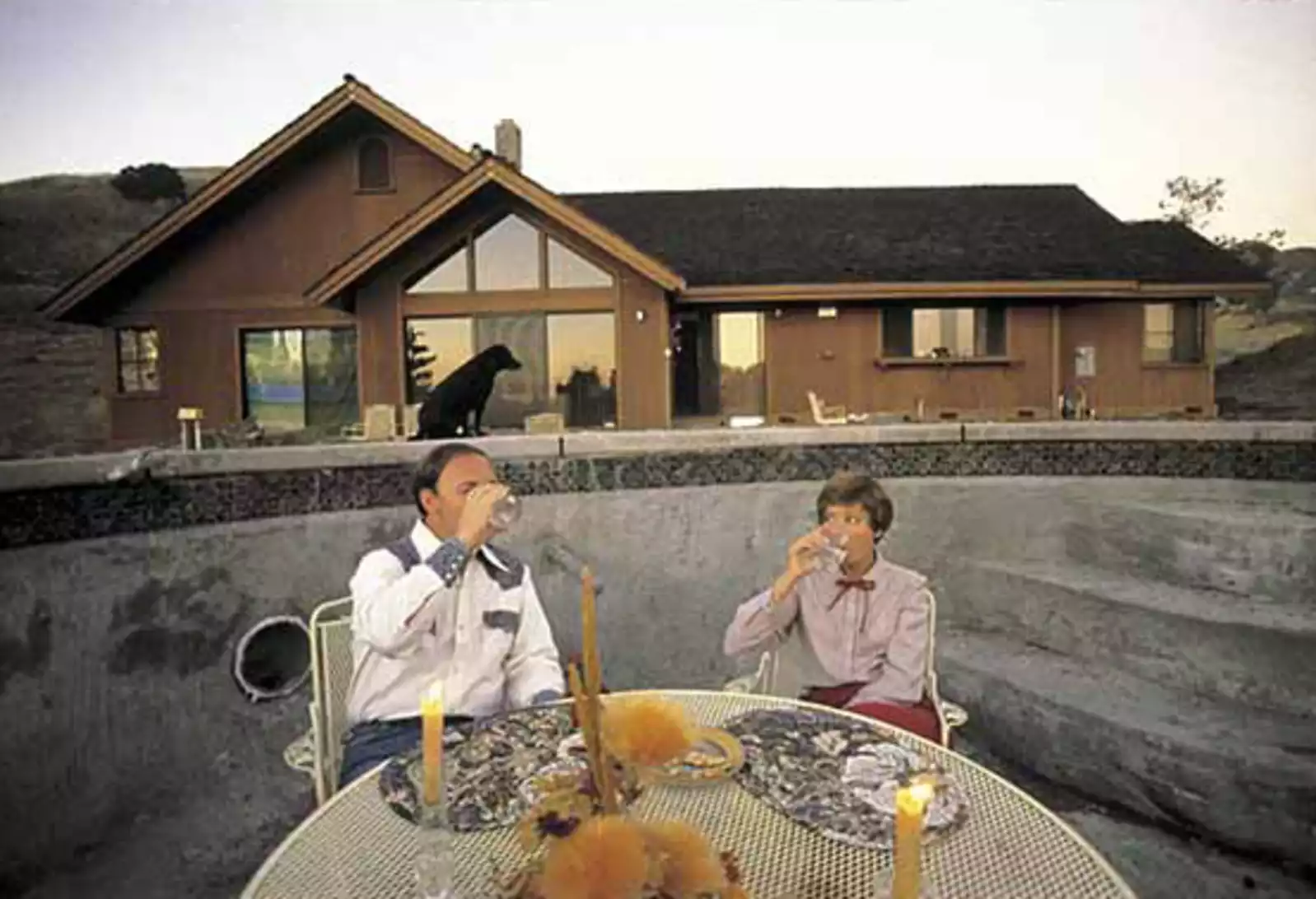

There is something of psychic zero in Bill Owens’ 1971 photograph Typical Californian. A couple in bolo ties sits at a set of patio furniture outside their bungalow in the gathering dusk, having a cocktail. A small plate of dry crackers stagnates between them, and their placemats are even more unappetizing, a fungal swirl of earth tones and white. They sit, not on the lawn, but inside an empty swimming pool, its walls composed of unpainted grey concrete. Has the man decreed that they will use the pool come hell or high water—or, as it happens, no water? Her tanned face is bored and resigned, his obscured by the glass of clear liquid—probably gin—that he’s tilting back, giving himself a piggish snout.

The photograph is absurd without being funny; the couple aren’t dining pool-bottom as a lark. I would ask if they know where they are, but something about the silence between them suggests that they are only too aware. Perhaps they (and their marriage) are in a drought, refusing to concede that the days of luxury and ease are gone by. They aren’t pretending that the pool isn’t empty; they are pretending that its emptiness is not a harbinger of something wrong. “I meant to do that,” you can almost hear him say, as though passing off a bad parking job.

Part of the mystery of the drained swimming pool is the mixed message conveyed about its availability. The Typical Californians don’t ignore the pool, but rather obey some subliminal call that tells them to use it, if not in the usual way. They are still impelled to place themselves inside it, to fill that echoing space. “Pity the bathtub its forced embrace of the human form,” writes the poet Matthea Harvey, but the swimming pool’s embrace is looser, more contingent. The swimming pool issues a challenge: to make the most of life’s fleeting pleasures. Being caught out, at summer’s end, is a failure of hedonism. Too late, the water behind bars seems to say with its many rippling tongues. The empty basin doesn’t speak its disdain, only stares.

It’s me, of course, who is staring. I’m staring at Bent Pool, a Miami installation by Berlin-based artists Elmgreen and Dragset, mounted in 2019. It’s six metres high, standing in a patch of grass by some palm trees, and it’s a swimming pool folded in half. It creates an aluminum Arc de Triomphe, an upside-down U-shape complete with diving board and ladder. The concave outer surface is turquoise, and its inner curve looks, if you were to pass under its white archway, like an enormous molar. Its twisted artificiality is meant to reference Miami’s climate-changed reality of storms and floods; the pool is designed to frustrate, inviting an expected action that can no longer be completed. In this sense, it recalls another swimming pool work by the duo, in which they recreated an exhausted and mildewing public pool inside London’s Whitechapel Gallery. Brown autumn leaves scudded over the bubbling paint of its floor, and a broken light fixture dangled, still dangerously illuminated, over a patch of rubble. “Civic space is really in danger,” Elmgreen told an interviewer for Artspace, noting that, over the past decade or so, many public pools in Europe have been converted into private spas or shopping malls.

When municipal pools are emptied they revert back, not to a state of nature, but to a state. Walking the chain-link perimeter of my neighbourhood pool, I’m struck by the many signs I’ve never noticed while the pool was full of life. NO RUNNING NO PUSHING NO DIVING NO SMOKING. Perhaps what drained the Typical Californians of life was that their pool is private, not public. In the darkest days of the Second World War, George Orwell wrote that hope for a new society was being born in the new middle class, in “the naked democracy of the swimming pool.”

I’ve always found private swimming pools sad; they miss the point so squarely, hiding away in lonesome luxury what is fundamentally an experience of communion, of gorgeous animal joy. During opening hours, a public pool is brimming with all shapes, sizes, and colours of humanity. A private pool is empty more often than not.

*

At first glance, the still photos showing Leandro Ehrlich’s installation Swimming Pool are frightening. From above, the viewer looks down at a swimming pool full of people who appear to be stranded on the bottom, underwater. Fully dressed, they look up beseechingly. My mind floods with lost boats carrying migrants across the Mediterranean, whole families drowned together.

But the water in the pool is an illusion: a thin glass platform over the sunk pool holds a few centimetres of water, while the people below pace about its dry bottom. In videos of the installation, the way visitors explore the swimming pool space suggests all the embodied play and fantasy of a real pool. A woman in a red jacket crosses the pool bottom with her arms outstretched, making dreamy swimming motions to ‘propel’ herself through the space. A man in a grey suit follows, breaststroking the length of the pool. A man and a child lie down and kick their legs, flutterboard style. The man in the grey suit looks up at the wavering surface and takes a picture, his camera flashing red as he captures the watery image of the people above him looking down. Erlich’s installation gives us the public pool as spectacle, a theatre where our eyes are refreshed with the sight of one another, in as close to our natural state as public space allows.

Leandro Ehrlich’s installation Swimming Pool. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Ekabhishek)

The drained pool is inevitably a reminder of mortality, of life and motion swirled away, leaving nothing but an empty shell. But in its emptiness, there is promise of renewal. The poet Brenda Shaughnessy writes, of a tract of half-finished houses: “Still we look for ourselves in these ruins or in that future, half-believing some half-finished half-razed self has only been half-projected onto it.” An empty swimming pool is an intentional ruin, both finished and unfinished, its incompletion integral to its utility. It marks a moment of reassessment: the self who swam here in months past is gone, no longer borne easily afloat, but set down to walk the winter on solid ground. There can be a galvanizing shock in breaking the fantasy.

Among my favourite depictions of drained pools are the commercial photos used to advertise pool-painting services: workers in coveralls and hardhats, masked and goggled, walking the deep end like astronauts, painting lunar craters aquamarine. Someone is already working to sustain our illusions for another season.