The Perfect World Does Not Decay

If she can’t keep her own plants alive, Tatum Dooley is at least going to figure out the artistic value of a fake one.

After years of success all of my plants suddenly died. It started with the leaves of one turning black. Then, as if the infection was airborne, the other plants all started to wither away with differing levels of dramatics. I was ruthless, throwing out each plant rather than trying to revitalize them. Each time I threw out a plant, I remembered its origin: a clipping from a family member, a housewarming gift from a friend, or a hanging spider plant from someone who had passed away. I felt remorseful that the plant’s history ended with me. I was hard on myself; a simple refrain echoed: “I can’t even care for a plant.”

The plants were one thing too many for me to handle. They were also the most disposable.

My mother suggested I buy fake plants to end the carnage. She sent me listings of realistic-looking plastic trees and rubbery succulents. I dismissed her idea out of hand. The purpose of having plants shouldn’t be aesthetic, but to engage in the act of caring for a living thing in your space. If I wasn’t responsible enough to care for a plant, I shouldn’t have any.

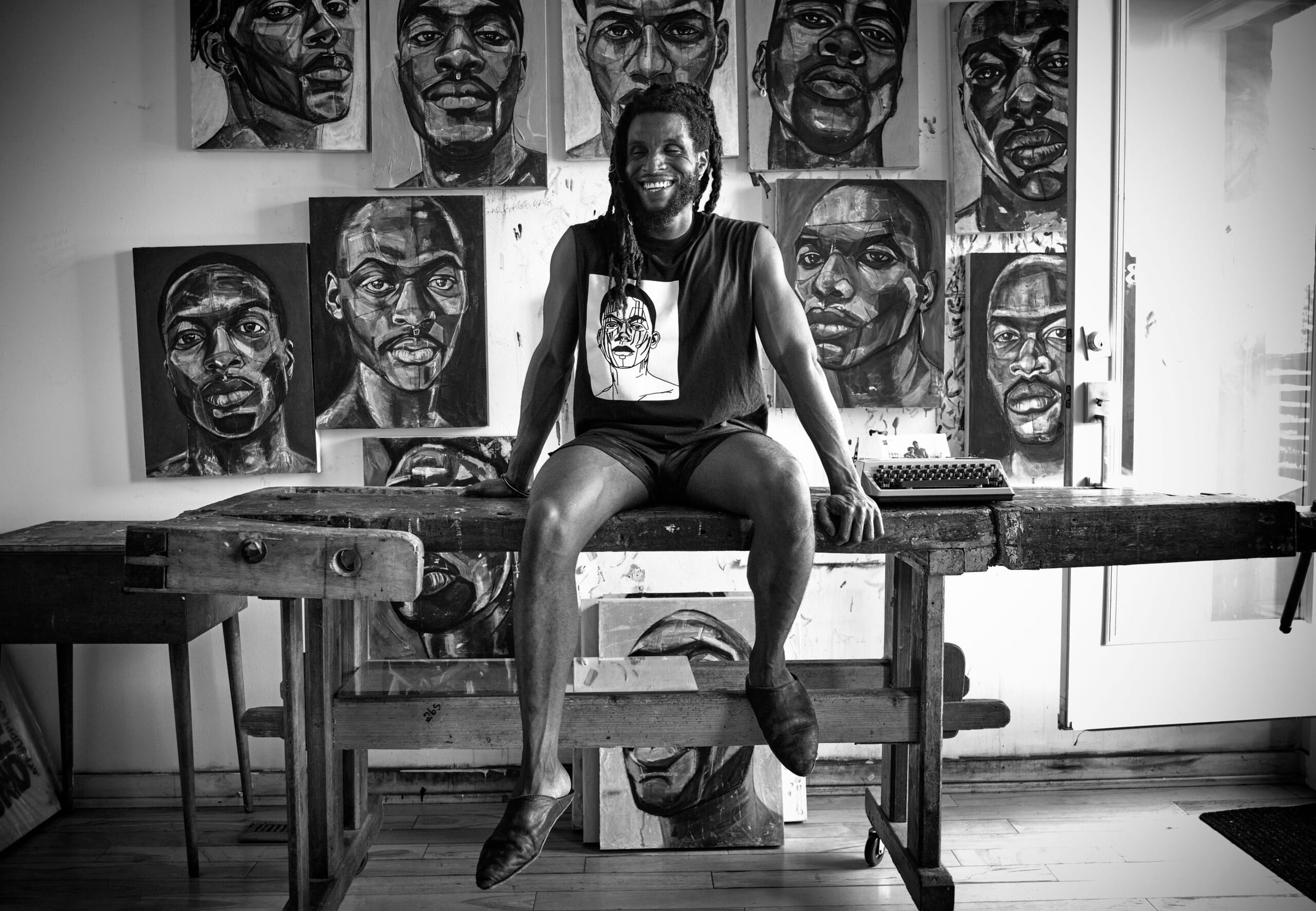

Artists, on the other hand, have no problem with fake plants, flowers, and fruit. It’s a trend that aligns with the art world’s preoccupation with fakes and forgeries. If I refuse to have fake plants because I see it as lazy, artists negate this line of reasoning by meticulously crafting trompe l’oeil recreations that disorient the viewer and question what is real and what’s fake. Artists depict the world around them, but painstaking recreations take things to another level. What is the point of making an exact copy of an object when we have the real thing at our disposal? Is it a show of technical proficiency—an artist brag? Or something deeper?

Plants and art aren’t that dissimilar in ways beyond whatever aesthetic pleasure they provide. Plants and art both necessitate care, specific weather conditions, and frequent upkeep. There’s a premise in the art world that people don’t own art, they’re simply caretakers of it for the next generation—stewards of culture and heirlooms. Just as I was preoccupied with my plants’ origins, art exists across generations. Generally I’ve found that taking care of art is a lot easier than caring for plants. For one, plants are living, and art, most often, isn’t.

Ever since the 1980s, the American sculptor Robert Gober has been fixated on creating impressively realistic duplicates of things from the world around him. They are objects often of a domestic nature, whether doors, sinks, a wedge of cheese, even a human leg. Apples are another recurring motif in Gober’s work. About one of his first major exhibitions, at Dia Beacon in New York City, Lynne Cooke wrote in the exhibition text: “Ascertaining which are genuine and which not soon gives way to the melancholy realisation that all are at the least plausible.” Gober introduces philosophical questions of what is real and what isn’t, stressing the thin line between the two. In the Dia Beacon exhibition, the entire gallery was encompassed with a vista of trees and plants, painted by set painters. When looked at closely, it becomes clear that the vista is incoherent: the woodland scene repeats and folds back on itself. In another piece, Gober carefully reconstructs a floor of moss, disrupted by a drainage pipe.

Fake plants have come a long way from what they once were. I’ve been duped more than once by a replica plant or flower, needing to get up close and touch its leaf before determining if it was alive or a fraud. Gober’s work puts the viewer in the position where they’re forced to discern for themselves the real from the fake, only to discover the difference isn’t as great as they might think.

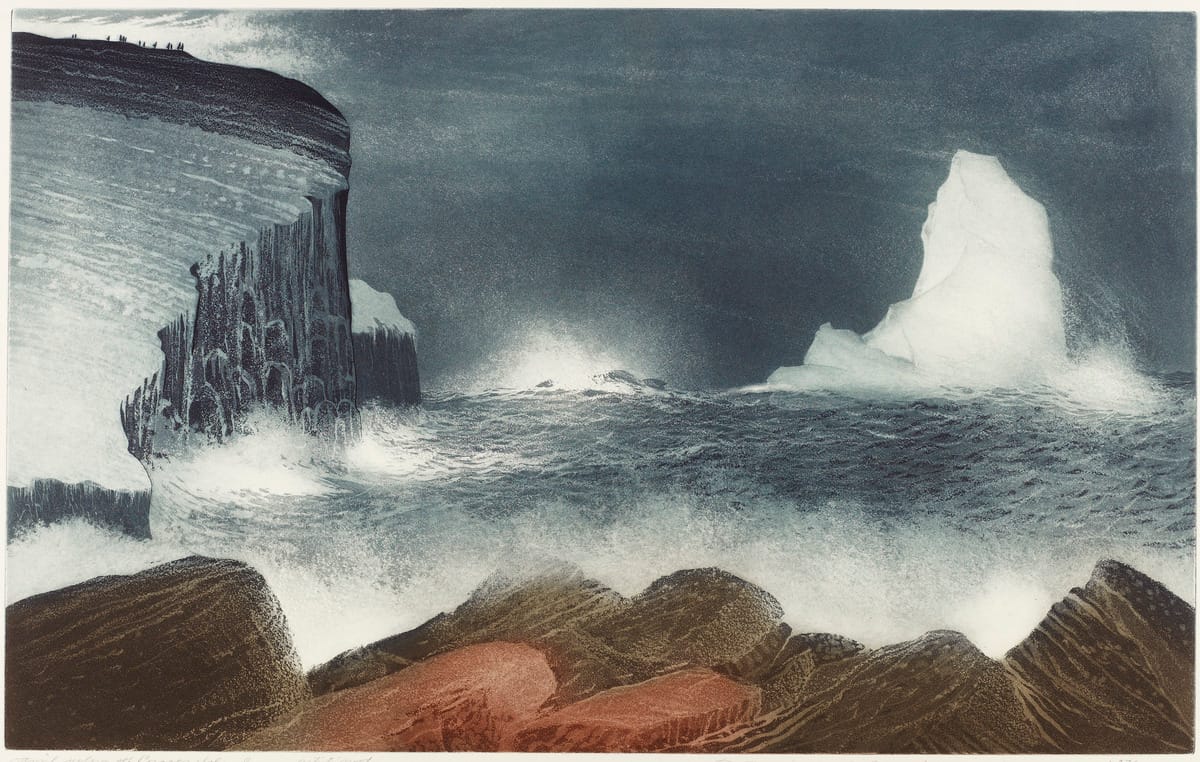

From an ecological standpoint, the uncanniness of these artist reproductions convey the message that the “real” object, the source material, might not always be around. As we collectively stare down environmental uncertainty, Gober’s work could well outlast the objects he is recreating. Writes Cooke: “All simple, straightforward answers to the question of what kind of immediate and authentic experience of nature is now possible, given the spuriousness of these outmoded through persistent cultural myths and the bleak actuality of ecological and environmental pollution also, appropriately, enter the province of doubt and become subject to close scrutiny, and hence skepticism.” An undercurrent of politics runs through Gober’s oeuvre. If people won’t pay attention to the original—whether it be nature or physical newspapers detailing the world’s horrors—Gober forces the viewer’s eye by translating the forms into art.

Gober’s work is unnerving in how it forgoes ephemeral qualities in place of permanency. The art world hates the ephemeral; the whole point of art is for it to last forever. This is partly why the Just Stop Oil protests target precious artworks to bring attention to the climate collapse. Images of soup smeared on paintings have gone viral over the last few years, causing an uproar in the art world. The effectiveness of such actions, however, are questionable when the reaction seems to be: You’re doing more harm than good by attacking what we all collectively love. Still, though I sometimes have a knee-jerk response to these protests, I think I understand them. Why do we place so much more value on the permanency of one thing, art, rather than another—namely, our planet? All the art in the world won’t matter if we don’t have anywhere to house it.

A noteworthy thing about fake plants is that they rarely show signs of decay, like a well-cared-for art piece. They tend to be pristine, perfectly pigmented, and taut. Fake plants have a perfection that is impossible in the real world. Perhaps that’s where my distaste for them lies—What in life is ever so perfect? Why do we opt for the easy way out rather than work to protect the delicate ecosystem we have? So afraid of death, of anything ephemeral, we’ve opted for the dystopian promise of an illusory forever.