The World as Dinner Party

In the elaborate, phantasmagoric social tableaus of artist Andie Dinkin, Ariella Garmaise sees the euphoria and hauntedness of Jewish traditions.

“To give formal dinners in the rain forest would be pointless did not the candlelight flickering on the liana call forth deeper, stronger disciplines, values instilled long before. It is a kind of ritual, helping us to remember who and what we are. In order to remember it, one must have known it.”

– Joan Didion, “On Self-Respect”

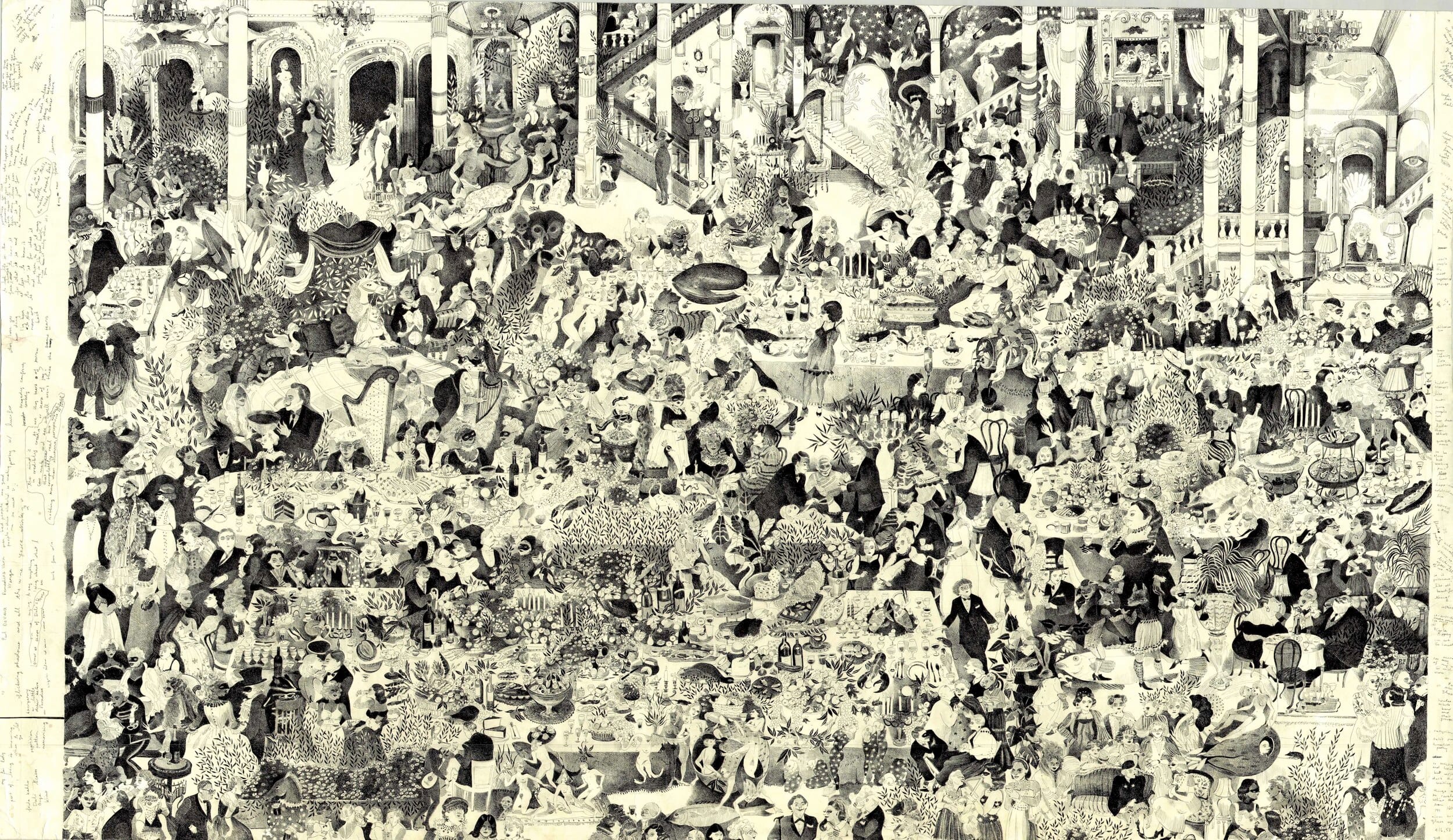

According to Jewish law, to conduct a prayer service, a minyan is required. A minyan is a ten person quorum. Though it is possible to pray by oneself, certain prayers, it is said, are so holy that they require the power of a congregation. In Andie Dinkin’s phantasmagoric social scapes, of elaborate dinner parties and tennis matches and garden picnics, I see it over and over again, iterations of the minyan.

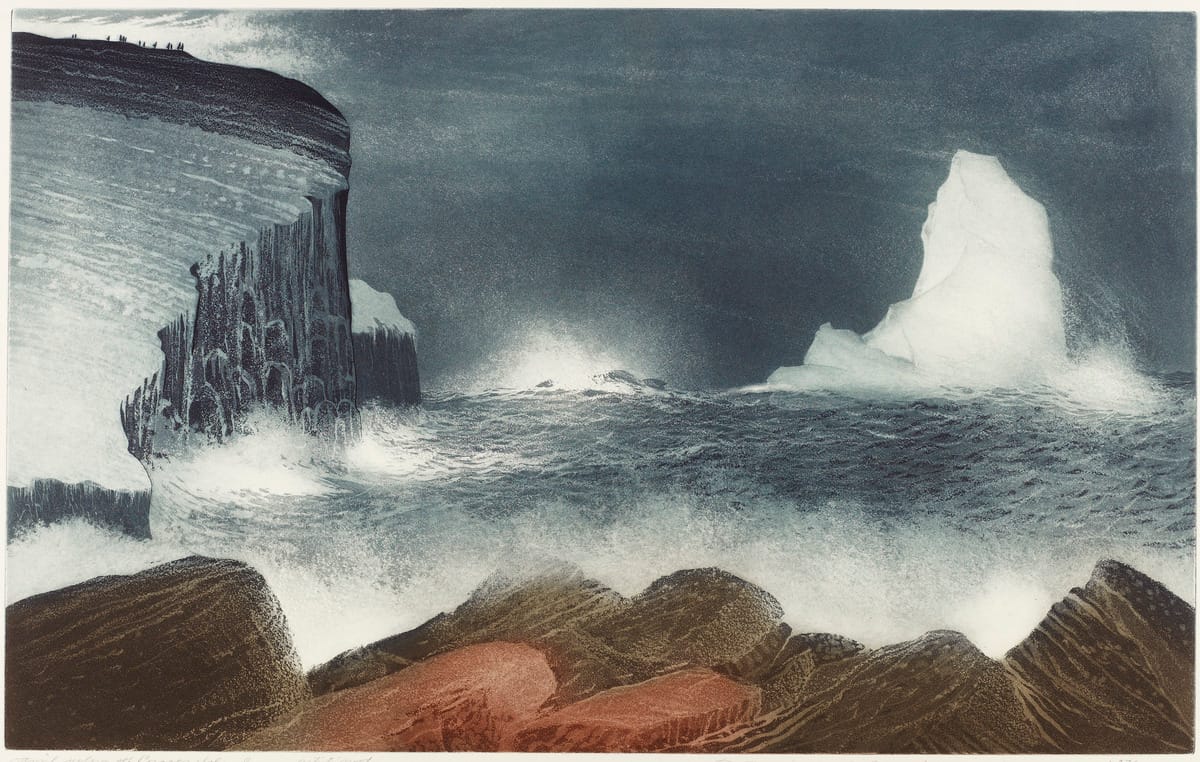

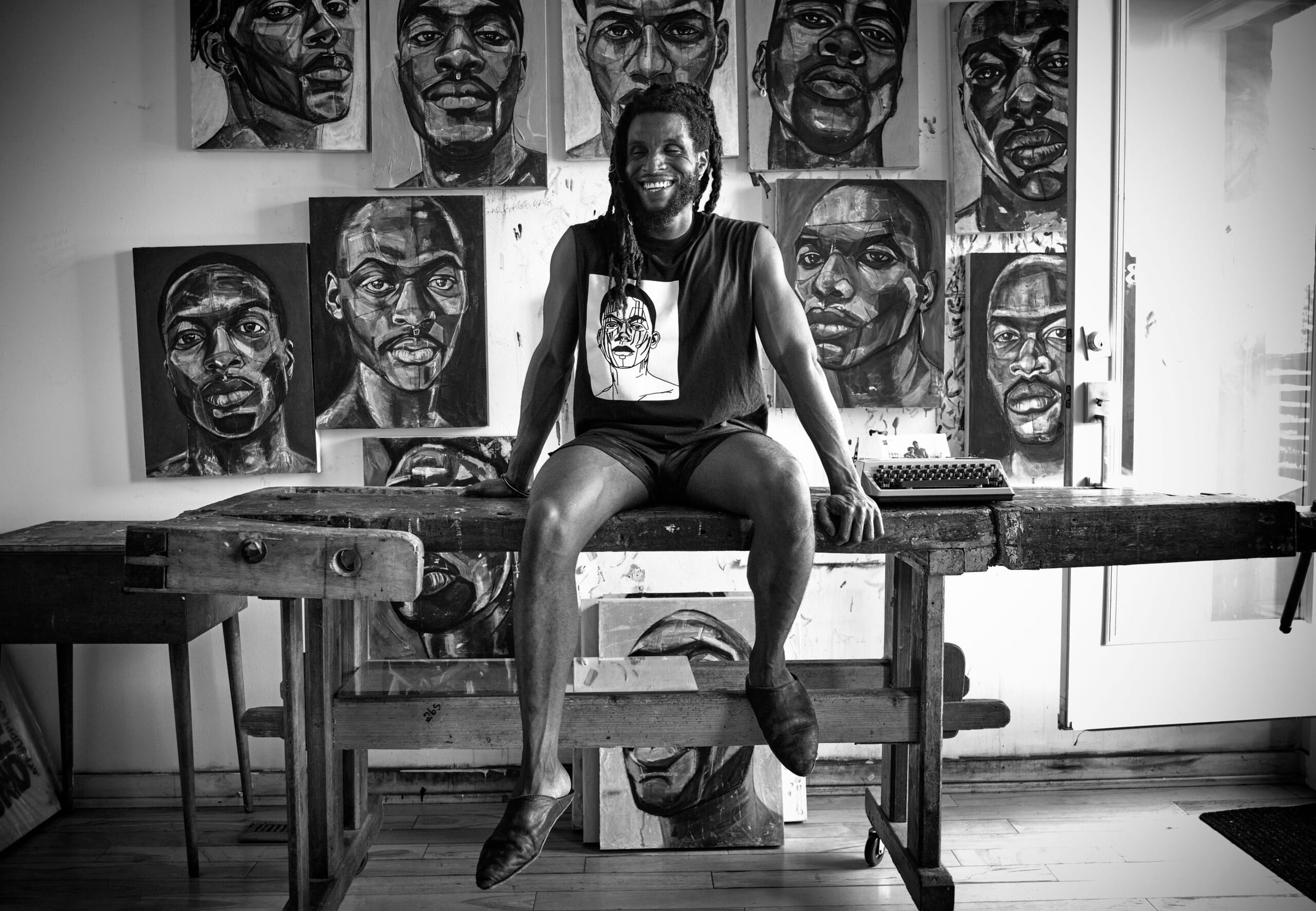

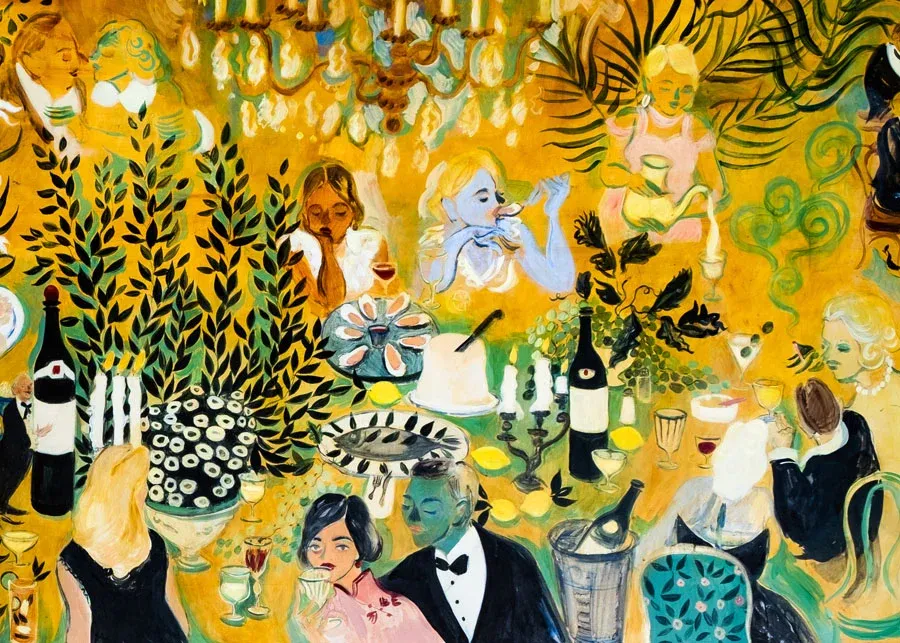

Dinkin is an LA-based artist, who layers acrylic paint, gouache, ink, and charcoal to create her dreamlike tableaus. Take Heat (An Ode To Florine Stettheimer) from her solo exhibition last year at New York’s Half Gallery. Dinkin frequently takes inspiration from Stettheimer, the heiress of secular Jewish-German immigrants, and her infamous New York salons. (In 2017 the Jewish Museum in New York held the first retrospective of Stettheimer’s work in over 20 years).

In Stettheimer’s version of Heat, the Stettheimer sisters and their mother wilt at the family’s summer residence in Bedford, New York, while a birthday cake for the matriarch sits uneaten. In Dinkin’s rendering, the composition isn’t quite so sparse: the table teems with bottles of wine and martinis, coffee mugs, a half-eaten loaf of bread, and remnants of a turkey. Maybe these patrons are in repose not just to withstand a sweltering heat, but to digest a well-enjoyed meal. I see it, the wine, the bread, the meal meant for five that could really feed a dozen, the candelabra that blazes in the backdrop: the sluggish hours after Shabbat dinner.

In Midsummer Night’s Dream, a piece Dinkin displayed as part of a group show this past summer at Manhattan’s Mona Rowe Gallery, more guests—some human, others angelic—surround another table crowded with wine and bread. A blonde woman dons a donkey hat, in obvious reference to the character Nick Bottom, but I can’t help but think of Chagall more than Shakespeare. Chagall first experimented with gouache when he painted The Green Donkey, and later revisited the subject in shades of ultramarine and ochre, looking back at his shtetl. The donkey is a relic of the old country, of the comedy and absurdity of tradition, but also an augur of hope, the steed upon which the messiah shall one day ride. It’s difficult to separate Dinkin’s folklore from that of my youth.

Dinkin’s paintings, with their vast domestic scenes and manifold references, are a sort of Rorschach test: my friend Charlotte hones in on the edenic greenery that frames so much of her work, another friend on a portrait of former Real Housewife of New York Sonja Morgan sandwiched between Leonora Carrington and Frida Kahlo, another on the recurrence of Greek mythology. I only see Jews. Dinkin’s work, I should mention, is not explicitly, or really maybe even implicitly, for that matter, about Judaism; her dinner scapes feature oysters and lobster and countless other tref delicacies. To my knowledge, she does not discuss Judaism publicly anywhere. So perhaps it is evidence of my own pareidolia, what, in a sense, Rorschach was testing for—a propensity to see symbolism or pattern where there is none—that in Dinkin’s work I can’t escape the euphoria and hauntedness of Jewish traditions.

As has become usual, I first encountered Dinkin while scrolling Instagram, her vibrant universes glowing, sandwiched between photos of girls I once knew from high school and ads for a miracle bra. There was something anachronistic about coming across an image that required such total focus, that was not trying to sell me on a single product or brand or self-image but on the existence of an entire world, replete with its own characters and mythology.

Maybe it’s just seeing people sitting and eating together around a table that feels religious to me, an increasingly rarefied sight in an atomized world (how fitting that Gigi’s in Hollywood commissioned Dinkin to paint a mural to mark the reopening of post-covid restaurant dining). My synagogue, for example, which has one of the largest congregations in North America, regularly fails to meet quorum for weekday services, as religious affiliation in younger generations wanes. (What constitutes a minyan can be rather strict, if not oppressive: among more observant congregations it’s only men who comply.) Meanwhile, every Friday night I sit around a table with my parents and siblings and grandparents and WASP, but soon-to-be Jewish, boyfriend, in something of a minyan. And if I pretend it to be a chore, it’s all a facade, really, it provides me such comfort to know the week is bookended by Shabbat dinner.

Chagall left his birthplace of Vitebsk, Belarus to pursue a career as an artist, but when he returned to see what had become of the shtetl of his memory, he was overwhelmed by the urge to sketch and somehow preserve the traditions he saw obliterated.

“It’s only my town, mine, which I have rediscovered,” Chagall wrote in his 1923 memoir My Life. “I painted everything I saw… I was satisfied with a hedge, a signpost, a floor, a chair.” Is this what Dinkin is doing too, sketching a picnic basket or floral arrangement or a splattering of lemons, lest these ghosts of meals past be forgotten? Each of these iterations of the Jewish community, from Chagall’s shtetl to Stettheimer’s Jazz age salons to Dinkin’s mural at Gigi’s, suggest the endurance of some things essential: candles, wine, people around a table. In Le Repas des Amoureux (The Romantic Dinner), a 1980 piece that seems to foreshadow Dinkin’s work, Chagall mixes gouache, ink, watercolour, and chalk to depict a couple’s date. The man and woman sit across from one another, with a candelabra and some glasses of wine in between, an intimate moment save for the village children and chickens packing the lower quadrant. Love, Chagall seems to posit, is a community endeavour.

There’s a supernatural haunting in much of Dinkin’s work, sometimes amorous—in Ghost of Venus (2024) it’s the spectre of love that glows around the table—others quite sinister. My Favorite Ghost (2022) has a skeleton and reptilian creatures lurching towards a bare-breasted woman. A woman in a corner balances four candles atop her head like a caryatid, but the warmth of the flames are deceiving here: dramas and resentments bubble under the surface. Ghosts are, theologically speaking, dismissed as superstition in Judaism. Still, the Shabbat table has its own phantoms: of guests come and gone and traditions lost, of traumas endured, and generations vowing to continue observing. Just as the candle flickering recalls values instilled long before, and the very rituals that make me most proud to be Jewish and to sit at that table week after week, it casts a shadow on the horror that persists in the name of Jewish self-preservation. Selfishly, it makes my cheeks prickle in a hot shame, that I can’t profess pure pride in my traditions as I once did. It’s holy, the Shabbat table, but it can feel haunted, too.

In 2001, a Chagall painting worth approximately $1 million was stolen from the Jewish Museum. In a highly unusual instance of politically-motivated theft, the thieves left a ransom note stating that the piece would not be returned until there was peace between Israelis and Palestinians. The painting in question, Study for ‘Over Vitebsk’ (1914), shows a beggar floating above Chagall’s shtetl, preparing to go from door to door, evocative of the displacement Jews suffered in the Pale of Settlement. The painting was recovered some years later in a post office in Kansas, but it was never discovered who stole it. I like to imagine the choice of painting wasn’t random or just one of convenience, but intentional, a decision made by someone who saw that the suffering in Vitebsk had been weaponized to justify that same suffering elsewhere.

The Skeleton’s Holiday (2024), which Dinkin displayed in a group show at Los Angeles’ One Trick Pony Gallery, borrows its title from Carrington’s short story of the same name about a skeleton who has momentarily forgone his duty to death and sought some reprieve. “Have you heard the appalling moan of the dead in slaughter?” Carrington writes. “It's the terrible disillusionment of the newly born dead / who'd hoped for and deserved eternal sleep but find themselves tricked, / caught up in an endless machinery of pain and sorrow.” The skeleton continues to brush his teeth.

In Dinkin’s painting, a festive crowd surrounds a table yet again. A man gives his paramour a kiss on the cheek, another couple is prepared for a masquerade ball. One blue avian-like woman with a crown of flowers hugs the skeleton, as if unaware that he is without flesh. It is as if the patrons simply choose not to notice that among their midst is not just a skeleton, but some sort of grim reaper, whose face is as black as his witch’s hat.