Walking On a Wire—an Ode to Romantic Musical Couples

If singers and musicians are our culture’s de facto philosophers of love, what do their sometimes headline-grabbing relationships tell us about the art of creating together.

Today there is one story that arches above all others, a tale that seems to span civilizations. One myth so rich and timeless that it is told and retold, with names and details altered but the underlying archetypes intact, speaking directly to our collective unconscious. That story is the story of Fleetwood Mac.1

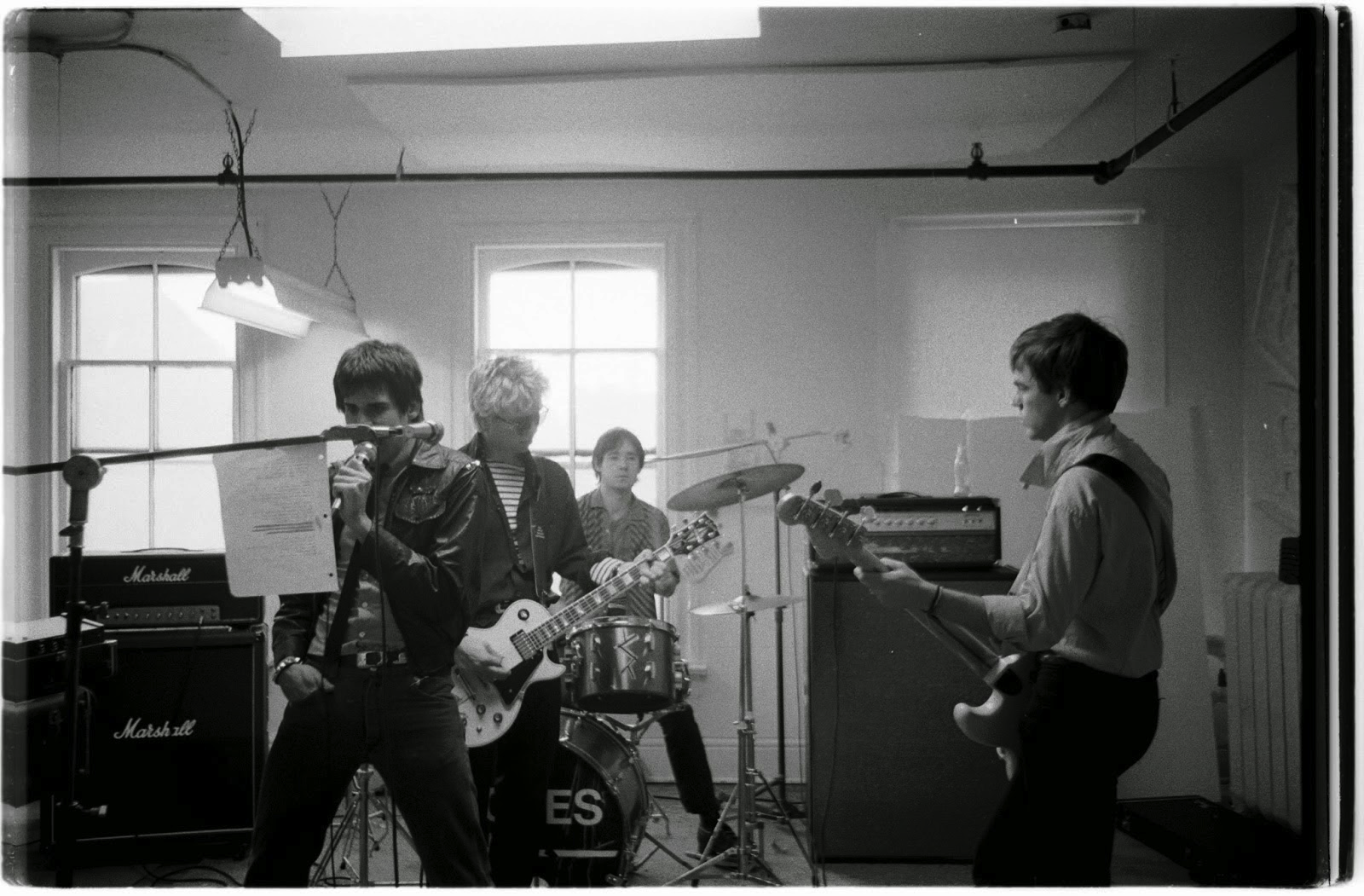

The shaggy 1970s rock band’s legacy of intra-band marriages, affairs, and divorces lends its template to this year’s Broadway hit Stereophonic by David Adjmi.2 The stage is transformed into one big recording studio so the audience can play voyeur to a fictionalized version of the famous love, sex, and cocaine farce-tragedy that was the making of 1977’s Rumors, still the tenth-highest-selling album of all time. Before that came Daisy Jones and the Six, the 2019 bestselling novel by Taylor Jenkins Reid, and last year’s Amazon miniseries adaptation, starring Riley Keough3 as the Stevie Nicks stand-in figure Daisy.

In pursuit of band-life realism, that production consulted with members of Toronto’s Broken Social Scene and Montreal’s Stars, each of which drags behind its own histories of internal hookups and breakups.4 Stars even had staged its own theatrical production at Toronto’s Crow’s Theatre in 2019, Stars: Together, recounting the band’s nearly Mac-level soap opera and celebrating its improbable intactness.

It’s natural for people in the same field to date, especially musicians, whose touring lives and arcane concerns (effects pedals, flatted fifths) can make non-musical partners an awkward fit. It also brings them into frequent close contact in shall-we-say-festive environs, where they may find themselves harmonizing figuratively and literally. It’s equally inevitable that fans are going to be compelled by the dating lives of the attractive and famous. But there’s something about pairings of musicians, whether fleeting or macro-sized,5 that can feel especially stirring or outrageous, depending how they align with our projections. Musicians are our culture’s appointed philosophers of love; they probe and testify to its force every day on stages and from speakers, and whisper its secrets in our ears via headphones. Actors are just hired hands playing roles, but people want to believe singers are singing their own actual hearts out. And how much more potent if their beloved is right there on the scene of the song to receive and answer the call, the Captain to their Tennille, the Camila Cabello to their Shawn Mendes?6

There’s a flurry of discussion now about the “parasocial” attachments fans are prone to develop with artists, celebrities, and so-called influencers. The simulation of one-to-one intimacy fostered by social media can lead to the delusion that you actually have a personal relationship with these strangers. It can be a harmless balm, or it can develop into an unhealthy fixation. At worst, as the suddenly megapopular young singer Chappell Roan protested this summer, it can lead to invasive behaviour when fans presume the objects of their attentions ought to reciprocate in kind.

It’s also an era in which the artist’s personal “story” is often taken to say everything about their art, and vice-versa. As Claire Dederer writes in last year’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, “Biography used to be something you sought out, yearned for, actively pursued. Now it falls on your head all day long.” However, Dederer also acknowledges that this “movement toward knowingness” has been with us at least since the beginning of mass media. Readers have always been consumed with curiosity about how much a novelist’s stories and characters are “based on real life.” In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Romantics cultivated intense emotional identification with both art and artists, leading to the Werther Effect, the ostentatious melancholy affected by readers of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, which is said to have led to a spate of youth suicide.7

From the early 20th century in arts and entertainment journalism, gossip columnists always arrived ahead of serious critics, and outsold them too. Before the Beatles could prod a generation to explore psychedelics, peace, or meditation, fans needed to decide which one they wanted as a boyfriend, which could also be a selfhood-shaping experience.8 And it still took nearly a half-century to get rid of the canard9 that Ono was to blame for breaking up the Beatles.

No wonder they disconcerted people, though; one of the most radical things about them was how they made their coupledom both material10 and subject of their art. Musical duos had always let listeners assume they were singing to and about one another, but now these two were narrating their lives explicitly, like a reality TV show, in songs like “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” “Oh Yoko!” and “John, John (Let’s Hope for Peace).” As the tetrapod was to the class mammalia, so the Ono-Lennons were to the class Kardashian.

Still, there is something about the long-term musical couple, the mix of personal and creative partnership, that I can find irresistible, at least as a screen to project my own fantasies onto. I started drawing up a list and reached nearly 140 examples within a couple of hours, from Sara and A.P. Carter in the 1920s Carter Family, to the 1960s freedom-jazz power couples of Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln and John and Alice Coltrane, to the dual couples within ABBA, to Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz (Tom Tom Club and the official opposition within Talking Heads) to the financial and cultural royal couple that is Beyoncé and Jay-Z a.k.a. the Carters today.

Perhaps it began for me with seeing Cher razzing Sonny on their TV variety show as a child, as well as catching up on the exploits of John and Yoko. But I particularly remember my high-school girlfriend and I becoming captivated by the mythos11 of Tom Waits’ turn-of the-1980s relationship with Rickie Lee Jones. We could spend hours picking clues out of their respective songs, and embarrassingly emulated them in our would-be-boho thrifted outfits.12 Later, I was one among an alterna-generation that adopted Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth as surrogate parent figures to the birth of our own attempts at cool. Though it wound up in infidelity and recriminations in 2014, I can’t regret admiring a partnership that modelled creative independence and apparent gender equity for going on three decades.

They don’t have to be straight partnerships, of course, and they don’t even have to be “successful” in the conventional coupledom sense. I’m so impressed by couples who break up but keep their band together, such as Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein, who were dating in the early days of Sleater-Kinney, split, but have carried on as one of the world’s greatest rock bands for decades.13 Then there’s Wendy and Lisa, the lesbian couple at the core of Prince’s Revolution, who went on making their own music for years thereafter, and still collaborate even though they’ve gone separate ways romantically.14

Even utter disasters between the musically starcrossed can be profound. The great British folk-rock duo Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out the Lights (1982) is often listed among the great breakup albums of all time, with songs such as “Walking on a Wire,” in which Linda’s bell-clear alto knells, “I hand you my ball and chain/ You just hand me that same old refrain/ I’m walking on a wire … and I’m falling.” On the subsequent tour, Linda famously kicked Richard in the shins on stage and threw a bottle at him in an airport for his betrayals. But the odd thing is that the material was written, in many cases, years before any such discord. It was almost as if the songs themselves summoned the marriage’s end into being. “I think that’s why the album is so good,” Linda later told Rolling Stone. “We couldn’t talk to each other, so we just did it on the record.”

Finally there are the truly swoonworthy. I can’t help being envious of MC Schmidt and Drew Daniel of the avant-electronic duo Matmos, 30 years and more than a dozen albums into their relationship, generating soundscapes out of found objects and queer art concepts. It seems to model companionate playful eroticism as much as the finest old Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn screwball comedy.15

Or Georgia Hubley and Ira Kaplan of the foundational New York-New Jersey indie band Yo La Tengo, joined by their close friend James McNew on bass. Their songs across more than three decades seem to trace the mundane ups and downs of coupledom with a sometimes hushed intimacy, sometimes raucous celebration, while always refusing to disclose more than hints.16 But again it’s the example they set of making a sustainable life in art together that is the most touching and loveable.

Kaplan told an interviewer last year, “It’s the only thing I know, so I have nothing to compare it to, but it’s great. Otherwise, we probably wouldn’t have lasted this long, the marriage or the band. … [Not] every day of work is a great day at work. There are times you wish you could just come back to the person you care most about. Georgia can’t do that, I can’t do that. [But] it’s the rapport that the three of us have. There are many bands that thrive on conflict and competition within bands, we’re not that kind of group, and that springs from the married couple at its core, and we try to get along. We try to be better than the sum of our parts. It’s as much of a challenge for James as it is for us.”17

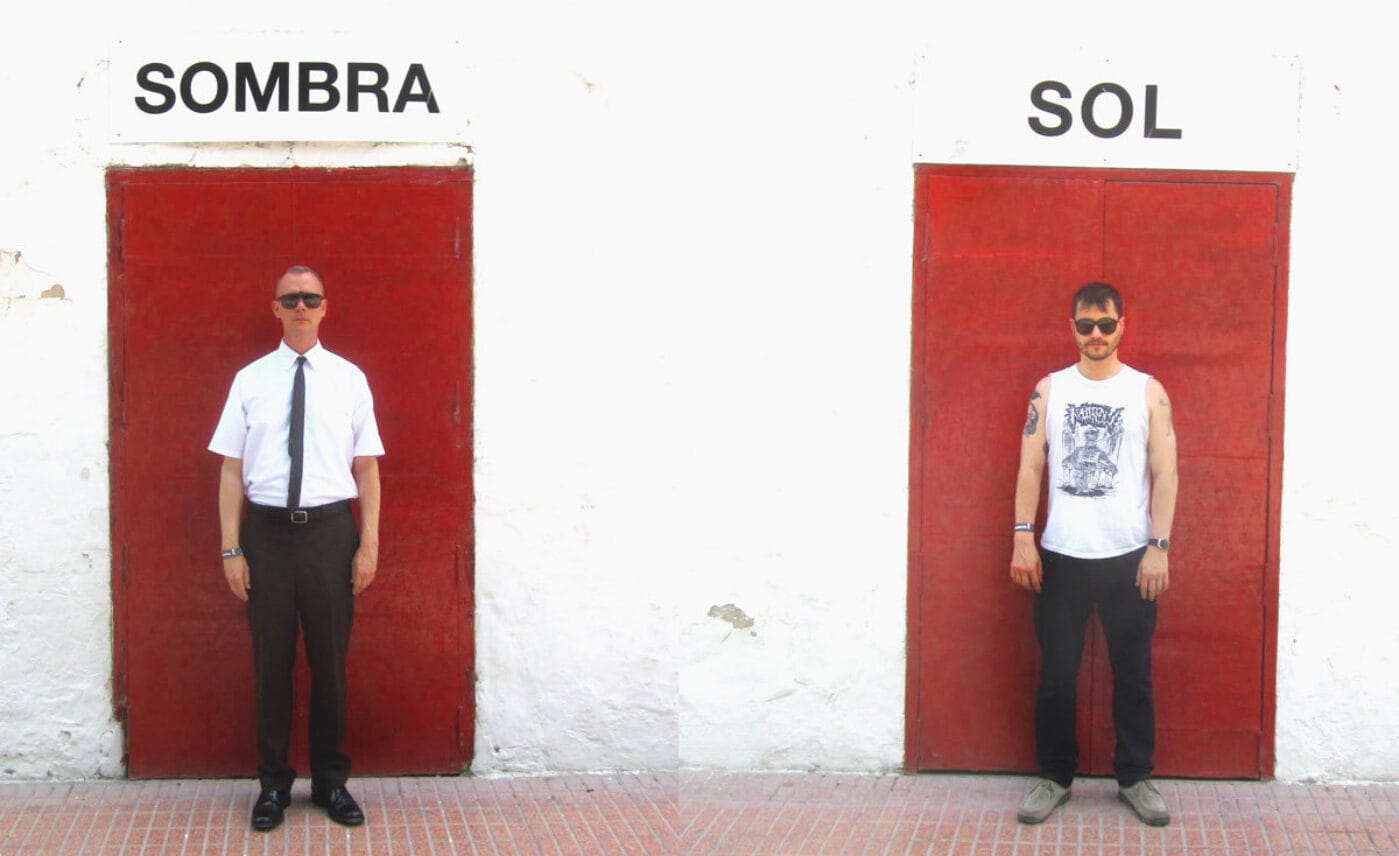

Similarly, the U.K. band Everything but the Girl, with its distinct synthesis of songwriting and dance beats, has been a joint project of the couple Tracey Thorn and Ben Watt since 1982—though they didn’t make their relationship public in the band’s heyday. They retired in the 2000s, married and had children. They’ve since made music and books and other projects individually. But last year they put out the eleventh EBTG album, the first in 24 years. Ever since 1992, Watt has also been dealing with a life-threatening auto-immune disorder, which made their experience of pandemic lockdown particularly intense. The thought occurred that if they were ever going to return to the band, it might be now or never. And when they began, that shared language came flooding back.18 As a listener, it was like returning to a favourite old haunt, long closed, and finding nothing changed except, of course, myself.

But then there are the points of no return. Guitarist Alan Sparhawk formed the band Low with his wife Mimi Parker on drums in Minnesota in 1993, making a sweet, distended, harmony-soaked sound critics called “slowcore.”19 As many have said, listening to Low could almost felt like eavesdropping on some private rite between the two Mormon believers. “I think it gave a certain license for creative intimacy and trust,” Sparhawk once said, “though it also made us each other’s harshest critics and harshest editors.” The couple continued through testing personal struggles, for a modest but continually increasing fan base, with various third parties on bass, making increasingly experimental music. Which all came to a stop with Parker’s death of ovarian cancer at 55 in 2022.

This fall Sparhawk is releasing a solo album called White Roses My God, on which the vocals are designed as an electronic slurry, pitch-shifted and incomprehensible. Nothing could make clearer the absence of the thick liquid velvet of Sparhawk’s former harmonizing with Parker, and the unspeakability of the loss, at least for now.

This is what really close listening to musical couples will remind you, that unlike in the Fleetwood Mac-inspired melodrama nearest you, real-life partnership isn’t all sex or schisms, all cuddles or coke spoons. It carries with it repetition, and fragility, and inexorable approaching loss, whether of love or of life itself. Music can make time feel suspended, but it can only make that long slow fall more beautiful, not arrest it. Stevie sang it herself: The landslide will bring you down.

- I’m ripping off one of Jack Handey’s “Deep Thoughts” jokes here, in which the punchline was “the story of Popeye.”

- The music for Stereophonic is written by Will Butler, who knows his way around the subject as a member of Arcade Fire, the Montreal-born band whose core is the married couple of Régine Chassagne and Win Butler (Will’s brother).

- Keogh is the granddaughter of Elvis and Priscilla Presley and daughter of the late Lisa Marie Presley, though not of Lisa Marie’s even more famous onetime husband, Michael Jackson.

- Amy Millan of Stars was engaged to bandmate and keyboardist Chris Seligman, but went on to marry another bandmate, bassist Evan Cranley. And that’s just one story.

- I’m sorry.

- Except that, in all too common a pattern, neither of those stores end well.

- How much this really happened is much disputed.

- Some pop scholars have argued Beatlemania as a girl-led mass movement was a precursor to second-wave feminism.

- Sexist, racist, etc., of course.

- See the bed-ins for peace and the naked Two Virgins album cover.

- Only discernible by triangulating magazine stories and other stray facts, and then making up the rest.

- That their tango ended in heroin addiction on one side and cruelly absolute rejection and denial on the other, we managed to ignore. Waits’ later relationship with Kathleen Brennan, who sobered him up, brought on his stylistic shift from retro to avant garde, and co-writes and co-produces all his music, turned out to be the worthier pattern to follow, but they live very privately, offering nothing to cosplay.

- Listen to “One More Hour,” an aching farewell from Tucker to Brownstein on 1997’s Dig Me Out—Brownstein’s said that she was such a compulsive compartmentalizer at the time that she didn’t even realize what the song was about. Which might be part of how they made it through.

- They have an album in the works with Annie Lennox, who was in another couple band that lasted longer than the relationship, the Eurythmics.

- For their 25th in 2019, they made an album called Plastic Anniversary, all sampled from plastic artifacts: “I ended with poker chips,” Daniel told an interviewer, “because to me, poker chips indicate a kind of chance element. That we don’t know our own future.”

- I’ve always considered their much-cherished 1990s ballad “Autumn Sweater” the best song ever written about having a panic attack before your wedding and wanting to elope instead. But I seem to be the only person who thinks it’s about that. Or a song about the unnamed contours of a minor marital fight might be called “The Crying of Lot G,” which you’re left to assume means Georgia.

- From clashmusic.com, 03/03/23. One definite downside of having a couple within the band is being the third or fourth wheel—Hubley and Kaplan have complained about McNew’s equal role in the band being neglected by press and some fans.

- “We seemed to have an instinctive feeling for the economy we wanted to use, the minimalism of the arrangements, the fact that the lyrics should be emotional, not sentimental,” they told the Guardian last year.

- The band did not.

1 I’m ripping off one of Jack Handey’s “Deep Thoughts” jokes here, in which the punchline was “the story of Popeye.”

2 The music for Stereophonic is written by Will Butler, who knows his way around the subject as a member of Arcade Fire, the Montreal-born band whose core is the married couple of Régine Chassagne and Win Butler (Will’s brother).

3 Keogh is the granddaughter of Elvis and Priscilla Presley and daughter of the late Lisa Marie Presley, though not of Lisa Marie’s even more famous onetime husband, Michael Jackson.

4 Amy Millan of Stars was engaged to bandmate and keyboardist Chris Seligman, but went on to marry another bandmate, bassist Evan Cranley. And that’s just one story.

5 I’m sorry.

6 Except that, in all too common a pattern, neither of those stores end well.

7 How much this really happened is much disputed.

8 Some pop scholars have argued Beatlemania as a girl-led mass movement was a precursor to second-wave feminism.

9 Sexist, racist, etc., of course.

10 See the bed-ins for peace and the naked Two Virgins album cover.

11 Only discernible by triangulating magazine stories and other stray facts, and then making up the rest.

12 That their tango ended in heroin addiction on one side and cruelly absolute rejection and denial on the other, we managed to ignore. Waits’ later relationship with Kathleen Brennan, who sobered him up, brought on his stylistic shift from retro to avant garde, and co-writes and co-produces all his music, turned out to be the worthier pattern to follow, but they live very privately, offering nothing to cosplay.

13 Listen to “One More Hour,” an aching farewell from Tucker to Brownstein on 1997’s Dig Me Out—Brownstein’s said that she was such a compulsive compartmentalizer at the time that she didn’t even realize what the song was about. Which might be part of how they made it through.

14 They have an album in the works with Annie Lennox, who was in another couple band that lasted longer than the relationship, the Eurythmics.

15 For their 25th in 2019, they made an album called Plastic Anniversary, all sampled from plastic artifacts: “I ended with poker chips,” Daniel told an interviewer, “because to me, poker chips indicate a kind of chance element. That we don’t know our own future.”

16 I’ve always considered their much-cherished 1990s ballad “Autumn Sweater” the best song ever written about having a panic attack before your wedding and wanting to elope instead. But I seem to be the only person who thinks it’s about that. Or a song about the unnamed contours of a minor marital fight might be called “The Crying of Lot G,” which you’re left to assume means Georgia.

17 From clashmusic.com, 03/03/23. One definite downside of having a couple within the band is being the third or fourth wheel—Hubley and Kaplan have complained about McNew’s equal role in the band being neglected by press and some fans.

18 “We seemed to have an instinctive feeling for the economy we wanted to use, the minimalism of the arrangements, the fact that the lyrics should be emotional, not sentimental,” they told the Guardian last year.

19 The band did not.