What If My Body is a Beacon for the World: Sensing with Neurodiversity

Adam Wolfond and his collaborators at Dis Assembly invite us to perceive and feel beyond the limits of the neurotypical “normal".

In the installation exhibition currently at Koffler Arts, we are invited by my son Adam Wolfond, and the collaborators, at Dis Assembly to feel. This invitation is a door to the open manner of perception that is the way of many non-speaking autistic people; a perception that is mobile, that moves with the sounds, the light, the wisps of wind, and also, the torrent of the gaze under which most autistic people encounter every day just walking down the street.

That walk is part of what you see in this exhibition. Walking is a pacing, patterning a bodymindworld that feels with what Adam calls “the atmospheres”; a permeable body that often can’t feel without the rhythmic pull of pace. The bodymindworld is entwined and relation is the key to living, and yet the ideology of positivism has contributed to cutting it apart.

Sometimes galloping to feel, the mouth touches the ground when one can’t feel the limb. A walk in the open field of autistic perception can move differently than the straight walk from point A to B. Like his “wanting ways,” Adam gestures toward the diversions that are attunements to the welter of the world. “Can a good body feel without another body?” Adam already considered this important question when he was only 13 years old. Now 22, using a device to speak with my hand on his back to activate his movement, Adam has published and been featured in the New York Times Magazine, recognized for a way of languaging (his word) that dances with the atmospheres. As he writes in his 2025 Master’s thesis:

“The ways that we really think and write come the way of varied patterns that push the words into a making-languaging that moves each pace as a pushing-phrasing that is thinking about the ways and paths that are like those caverns and we can’t see the way through but dance the feelings that assist us and that means my writing is the languaging-touching that I use to have words that you understand but have to dig through to feel.”

If we can feel our arms and legs, walks, like typing to communicate when even movement moves differently, ground us to this earth like a landing in the midst of flying; the pace, the touch, ground the autistic body when it can’t feel itself, it’s flesh unbounded that needs assistance to move. In typing to communicate with support, Adam has adopted our language and made it his own. The human and more-than-human relation is key here to navigate the tricky neurotypical world. A touch can cue a movement and this touch can be more than human. Stick in hand, “twallowing”—a word invented by Adam—to navigate these feels, these teeming atmospheres within which autistic lives tic, hum, yelp, is the answering; answering, as Adam says, the calls that beckon him; that bathe him in the affects of the world we all live in, but that most of us subtract from our immediate awareness. Because that’s what we have been taught to do: write in a straight line; sit still; look at me; watch that grammar; get to the point. These performative, “straight” efficiencies disavow peripheral, tilted, queer attentions.

Exceeding borderlines, territories… spilling over tables and chairs lined up in neat rows in the classroom to the boardroom, the autistic body leaks outside these lines that most of us “neurotypicals,” or neurodiverse people who have been taught and able to perform and pass, call normality. But what is normality but an imaginary—an image of what a body ought to be, not what is for many of us. And so, we have become a normopathic culture, obsessed with the right way to perform, to write, to produce. Noun, subject, object, period—we are rooted in the bifurcation of subject/object, my body/your body. Descartes continues to influence! We all cling to the Master’s language! Much too quickly we make the cuts—ab/normal, dis/ordered—to supposedly Other that which is different from the normopathic imaginary.

But there’s always more beneath the words, the surface. Neurodiverse people know this. Feeling is the attunement to the human and more-than-human world that is urgently needed because what we call “consciousness” is the mere tip of awareness; only what we have mistakenly conflated with “intelligence” which makes the cut. And still, autistic people, especially the non-speaking who experience the relationality of this world are characterized as disordered. The Martinican writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant, who understood the poetics of relation, suggests the opacity that belies the performative “clarity” that has excluded neurodiverse contributions to other ways of knowing. Differences in perception and movement continue to be characterized as non-compliant, non-relational, incompetent, and wrong. It is especially difficult to navigate the right ways to move for people who cannot perform it.

The autistics who are mostly non-speaking at Dis Assembly no longer want to answer to audiences about what autism is, but want to invite you to experience what it means to be neurodiverse, a different kind of human—perhaps we can say, a species of human. Which is why the recently invented term “neurodivergence” fails, because to diverge is a deliberate reinforcement of the concept of normality.

Neurodiversity is about the differences we all possess, some more visibly. Like biodiversity, we have come to understand the necessity of difference and relationality to live. From my point of view, as a mother and collaborator with many autistics, including my son, over the past 22 years, I say: thank goodness for the autistic expressivity that can be shared with us, if we are willing to open our minds, attitudes, and lives; to feel what it really means to be connected and attuned to the world and each other, however painful at times that might be. The staccato,undulating grammars that pace and pattern within the body, and the relationships that are created in supporting others in this gridded, boundaried, territorialized, surveilled, identity-obsessed world, are a welcome reprieve to the neurotypical modes of living to which we have all been commanded to adhere.

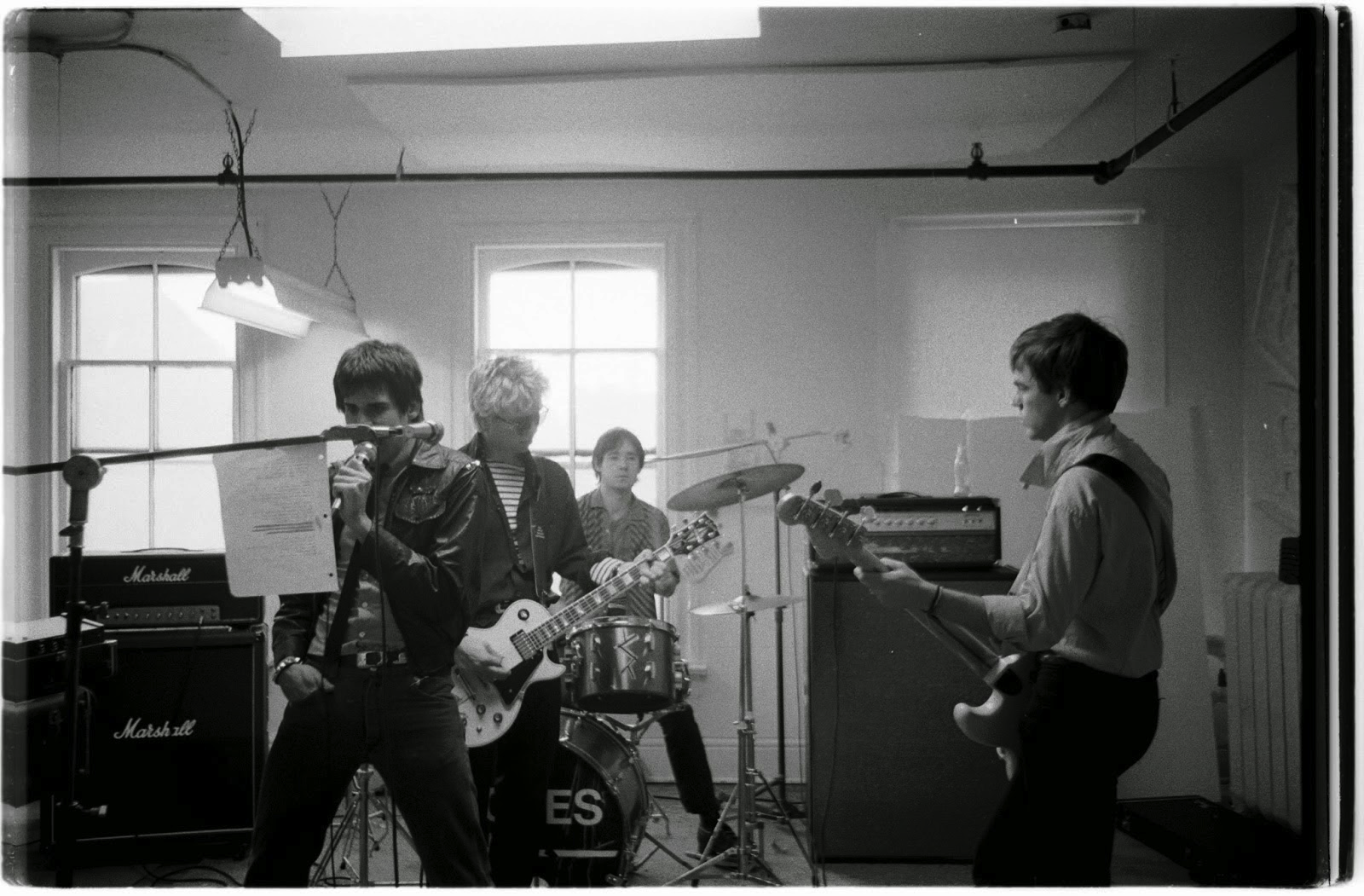

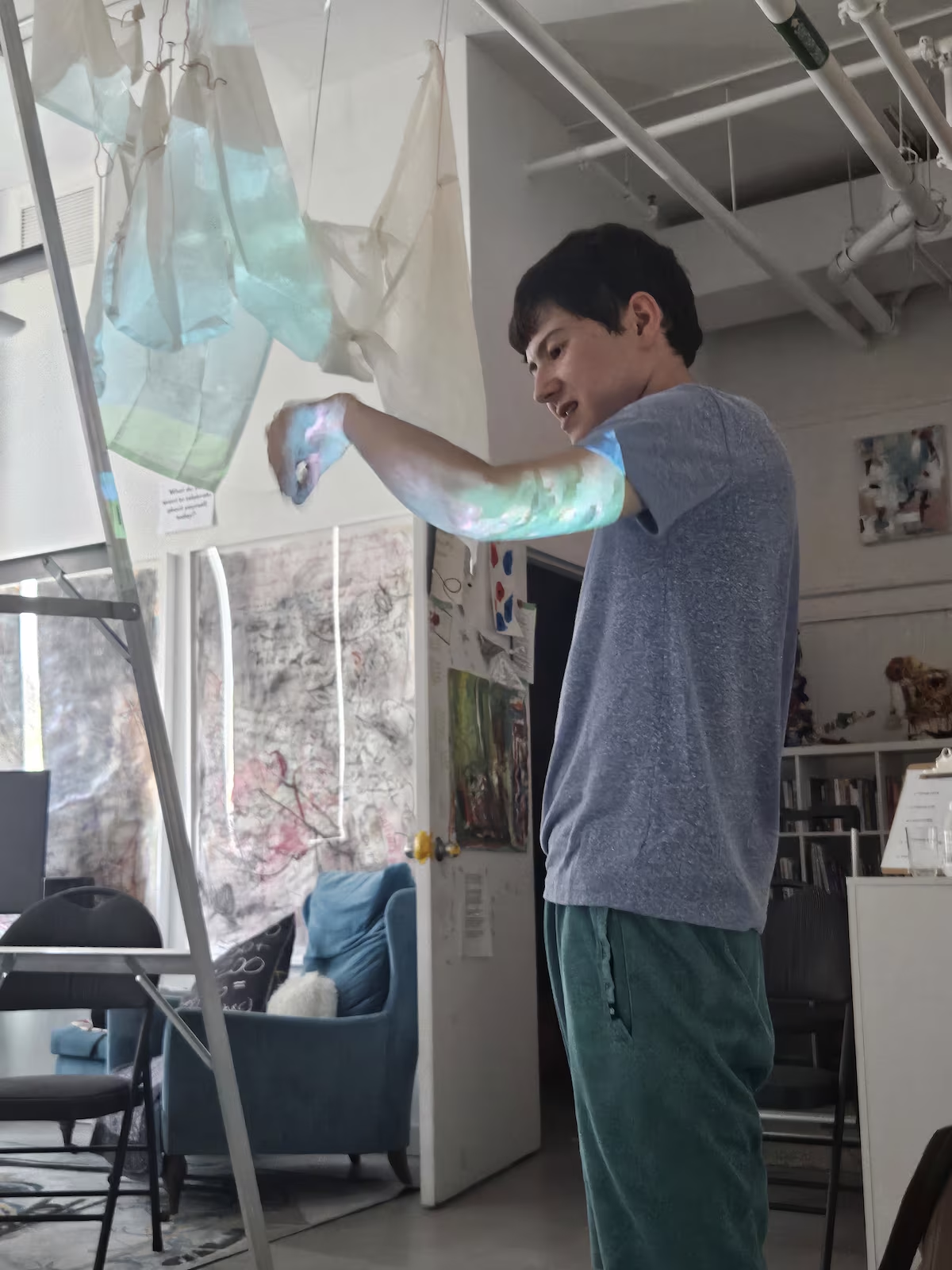

At left, Adam in the Dis Assembly studio, and installation view of What if My Body Is a Beacon for the World. (Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid)

So there is no standard narrative presented by this installation, which asks us not to gaze or create an after-thought narrative, but invites us to feel the welter of the world, the city, Toronto. The body-camera, the endoscopic camera, the Zoom recorder, and the hydrophone do not narrate a story about autism. This is a generous invitation for us to consider how neurodiverse/non-speaking autistic people can be supported in expressing in their own ways. How generous and brave the non-speakers at Dis Assembly are in making the attempts to share experiences lived outside the lines, and to experiment and open opportunities to bathe in this living-moving world and to share what relation really means.

We begin the installation with the typing movement—and this movement is difficult—the apraxia, the motor-planning that is required to type must think about where the arm is in space; where is my index finger; how do I move it forward? Most of us don’t have to ask these questions of our bodies; we don’t think about the fork and the distance we have to reach to pick it up so we can eat. We don’t need to “body borrow,” as Wolfond calls it, to move. Be it the touch I give on his back to activate his movement to the keyboard, or my voice to remind him where his arm is in space to pick up the fork. Or the arm-in-arm walks we sometimes take when navigating the busy city become too much.

There is a care here—a care that reminds what it means to make the neurotypical world accessible. And this care is never hierarchical, never one-sided, for Wolfond, my son, has been my most valued collaborator in reimagining how we can live together in the world, reminding us, yes, of the many barriers that have made our society inaccessible and unsustainable, but also how fulfilling it is to share creative ways of living.

To pay attention to the patterns of water that become a languaging, that becomes the music of relation. To understand a fractalized way of perception that the autistic feels-thinks. To foreground the stimuli that dominant perception (neurotypical perception) has been taught to background. To think alongside these paces and patterns that remind us there is more beneath the surface that we aim to master.

When Wolfond writes, “I am pace of my body and not language” (Wolfond, 2019), we begin to feel more than see; we are invited back into the wanting ways of “dancing” with the world. We see the details that the endoscopic camera sees, that autistic hyperfocusing, then move to the poetic aesthetic of water glistening on the floor, Wolfond’s poetry reflected on the perpendicular wall. The sounds coming from all angles from the Zoom recorder and hydrophone. We are immersed. And Wolfond and collaborators at Dis Assembly invite you in.