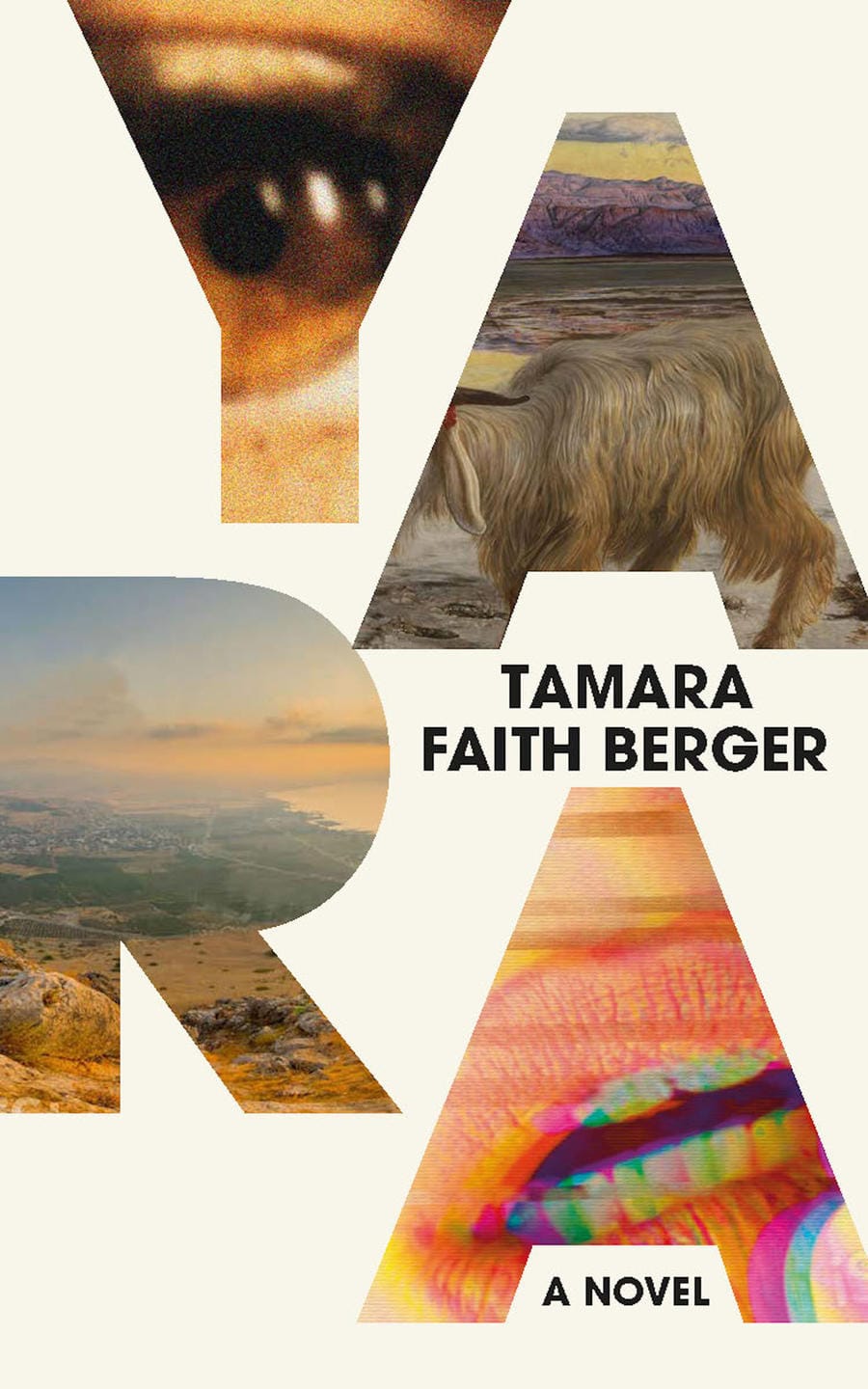

When the Scapegoat Is a Girl, Not a Country

Toronto author Tamara Faith Berger talks with Arcade about her latest novel, Yara, the different lenses on Jewish diasporic identity, and the malleability of language.

When I think of Tamara Faith Berger, I think of words that begin with the letter S. Berger is a writer deservedly celebrated for her candid writing of sex and the body, but after reading Yara, her latest novel, sex is maybe surprisingly not the first word that comes to my mind. In this book, Berger troubles, squeezes, and presses hard against the many ideas that fall into her frame: the sex tape, the nose job, age-gap relationships; Jewishness, feminism; Israel and Birthright, words and porn; consent, emotional abuse, and the many forms the scapegoat can take.

Scapegoat is the big S word in Yara, but the novel contains such a robust quantity of other S words that I kept a list on the front page of my copy: squirt, suck, smash, sweat, slither, spit, slut, sex, shutter, slip, slug, scuttle, slit. When I asked Tamara whether she noticed this when recording the audiobook, she said yes, but was more surprised by the amount of pink she’d infused into the novel.

Berger’s novels can be difficult to summarize. There are no straight lines, no straightforward timetables (in this interview she describes her writing process in similar terms). Past, present, and future tenses coalesce. Yara takes place in 2006, and its three parts form a sort of world tour of Jewish identity, sex, and the Internet: first to Israel, where Yara is sent on a Birthright trip by her mother (this section is called “Birthright”), then Toronto (“Hocus Pocus”), then California (“Rightbirth”), all the while rehashing and negotiating the fallout of certain events that took place in her native Brazil that led to her departure: namely, a nose job, a sex tape, and a manipulative girlfriend ten years her senior.

Yara’s three parts all begin with the same-ish sentences, variations on a theme. “That sentence was always there for me, from the very beginning,” she told me. “I’ll take anything that helps me structure a novel, and repetition really, really does.” These are the three beginnings: “I arrived in your country in August 2006. Shalom, the only word I knew in Hebrew.” / “I arrived in your country August 2006. Scapegoat the word followed me from Israel.” / “I arrived in your country September 2006. Porn, the one word everyone understood.” I cite them here to underscore the importance of words-as-words for Yara, whose native language is Portuguese but whose experiences in this novel are mostly in English. Yara collects words in English—scapegoat, which she first hears as noun to describe what Israel “always is” by Aloni, her Birthright leader; feminism, which she wore “like a coat” after hearing it in a university classroom; as well as the words authority, dick, pine cone, pussy.

In a 2018 interview with Jewish Book Council, Berger called her previous novel, Queen Solomon, her “first seriously Jewish book.” Narrated by a troubled, Kafka-obsessed, Jewish-Canadian teen, the novel tells the story of Barbra, an Ethiopian Jew taken to Israel at the age of five as part of Operation Solomon, a 1991 covert Israeli military operation that airlifted some 14,000 Ethiopian Jews before the fall of the Mengistu regime. When the 18-year-old Barbra comes to stay with the narrator's family one summer, she and the boy strike up psychosexual games of desire, fantasy, and violence.

Yara, then, unambiguously, is Berger’s second “seriously Jewish book”, taking up among its many concerns Birthright as a concept, the Jewish diaspora, and Israel as a place and power.

*

When you started writing this book, was Yara always going to be Brazilian? What made you want to explore the idea of the Jewish diaspora from a non-North American or European perspective?

Yara being Brazilian-Jewish was always there, and was always an important part of this story. Especially in Queen Solomon but also in Yara, I’m looking at the diasporic Canadian-Jewish identity versus the Israeli-Jewish identity. Queen Solomon also explores the Ethiopian-Jewish identity. And in Yara, there’s the Californian-Jewish identity too.

Yara, being Brazilian, has a side view on things we don’t normally see. For instance, she says how she didn’t grow up like Canadian Jews, with this very specific notion of what Israel should and ought to mean for the diaspora. She has her own rituals, and her own sense of family through her mother and grandmother. She’s just as Jewish as the Canadians and the Israelis—this is an idea that I’m invested in. I reject the raison-d’etre of Birthright that the creation of the state of Israel, or making aliyah [immigrating] to the state of Israel, is this more righteous, more brave, or higher form of Jewish identity. It’s not. It’s just different. Being Brazilian, Yara personifies the equality and multiplicity of the Jewish diaspora and she also echoes famous Jewish Brazilians: Yara Yavelberg, notably, and Clarice Lispector, possibly.

There’s a passage early in the book where Yara asks herself: “What did it mean to discover yourself as a Jew? And why did I think about the cam girls right then, too? It felt like some thought that was broken halves of the same worm.” This passage exemplifies so much of what you do in your writing, on the level of the sentence or paragraph: the smashing-together of two things, and watching how this friction energizes thought and action.

This is definitely one of my interests in writing, the friction of putting things together, exactly as you put it. And I know it can steer and skew into really problematic places, but I’m curious about Jewishness and Jews in porn, or Jews and porn. There are a lot of Jewish people in California pornography. White supremacists have a big run with this!

In that line you cite, I am trying to mend a thought, but also trying to defang it at the same time. I remember an editor who would lightly scold me and say, like, stop reading the white supremacists, stop reading the conspiracy theories, their brains are not that good! But I still find interest in it—like, yes, there’s a crappy idea, but then there’s all this stuff underneath it. There’s history, aesthetics, stereotypes… I think there’s new and original thinking that can be brought into these tired, old tropes.

Andrea Dworkin wrote an entire book on this—Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation. Then there’s her big book, Pornography: Men Possessing Women, which is anti-porn obviously, but I find her brain really goes to these difficult spaces. She tries to rip things open and flood discourse with new thought, whether you agree or disagree with her. I think that in some way I’m trying to do something similar.

When Yara first learns the word “scapegoat,” it’s in the context of something Aloni, her Birthright leader, says about Israel always being the scapegoat—though Aloni never really articulates what exactly he means by this. Yara arrives at a different conclusion, rooted more in her own personal experience: “I thought, scapegoat is a girl, not a country.” Here I was reminded of the 2022 novel, Revenge of the Scapegoat by Caren Beilin, in which Beilin casts a satirical, surreal gaze upon Jewishness, chronic illness, and the trauma that is the family, as viewed by an adult who was once cast as the scapegoat for her family’s failings. Beilin’s theorizing about the adult scapegoat forms an interesting counterpoint to your “girl scapegoat” in Yara.

I loved reading Beilin’s book so much. I like all of her books. Yeah, I think I was conceiving of the girl scapegoat as a sex worker—the porn star as the teen girl, flicking her pigtails, being a kind of holy brat. She’s the scapegoat and she’s just there to be used and then shut off or put down, she doesn’t exist any more after she’s been used. But of course she does exist, even when the screen is dark.

I think of this girl scapegoat as having a kind of knowledge that we don’t hear so much about. In this book, we have the space to go really deep, to experience the experience of the girl who’s been blamed—for not feeling enough or for not feeling the right things; blamed for her experiments, for her language and for her mistakes. I think in Yara we get to follow this girl scapegoat through her exile to this place where we are not sure we want her to go. But she goes. So we go with her.

There is so much animal language in your writing of sex—amphibians, jellies, cows, dogs—and I’m wondering what you feel animal language gives to your representations of sex. There’s an echo here, too, with the narrator of Queen Solomon, who has just read The Metamorphosis and makes perpetual references to his experience of his body as an insect.

I recently came upon an article on a Jewish theological website about “species purity”. One of the stories about the Great Flood in the Bible is that God was furious with humans because they were cross-breeding women with other species. I’d never heard that God got rid of humans because they were having cross-species orgies! So God saved Noah and his “perfect genealogy” for everything to be ordered, in its so-called proper place.

This pre-flood story of cross-species sex, and hybridity in general, reminded me of porn—there’s a whole fanfic subcategory about cows and women and cross-breeding. Has there always been this fertile, transgressive mashup between the human and the animal? It seems to poke at all things religious, mythic, sexual… I think this interstitial space is alluring and it’s where I guess straight human verbs are inadequate when I’m representing sex.

Given that Yara is Brazilian, it was only around page twenty of Yara when it occurred to me that there’s this big question of language in the novel. I actually wrote this question into the book’s marginalia: “Is this novel experienced in Portuguese but written in English?”

It’s weird because I feel like you're almost in my brain! Yes! Obviously it’s a technical issue, right? I don't speak Portuguese, but that’s the first language of my character. So that is a bit of a problem. And I think it was only after I’d already written the book did I realize that—that while she is mostly speaking in English throughout the book, her main language is Portuguese. I think that in the space of literature, there are ways around this that feel imaginatively apt.

And her English, we understand, when she interacts with some Americans, is audibly accented.

Yes! And she is learning English, she has, as you mention, that collection of words that really stand out for her. This collection of words is there to focus on—both on the way they sound and their meaning.

Throughout the writing of this book, I was also trying to figure out that word—scapegoat, as concept, as stigma, as sound. So it was helpful to have a lot of this be through the lens of a character for whom English is a second language—a thicker, more critical lens through which to see some of these things.

Again, it goes back to her Brazilianness, which allows her to see things a little bit askance, skewed, de-centered, from the side. I know it's not super fashionable, because I think everyone right now is really interested in authenticity. But I think about these things a lot, and I’m interested both in characters whose vision is more skewed and in characters who are more centrally positioned. And I like to incorporate both these visions into my fiction and also be bold about it, you know—because the imagination really can go lots of different places.

This is an accented novel that takes up translation as one of its concerns, not only in terms of English versus Portuguese, but because Yara, towards the end of the book, is interested in pursuing literary translation in university. As a literary translator, my preferred metaphor for how I approach my work is that it’s like acting. Like an actor, the translator interprets a text, and the language moves through their body, their vocabulary. The resulting translation is necessarily shaped by the voice and body it passes through. Perhaps selfishly I loved that Yara becomes interested in and somewhat empowered by the concept of translation: “It was in Russian, the porn. But I had the power of translation.”

I really like that acting is the most apt metaphor for translation that you’ve experienced. My character Yara Yavelberg is experimenting with being an actress, while the real Yara Yavelberg was a psychology professor who became a revolutionary during the military dictatorship in Brazil. Her transition from professor to militant was facilitated by being in love. And while she was ultimately killed for this role-switching, I find her an inspiring and enigmatic figure who I desperately wanted to translate, even though I don’t speak her language.

In the spirit of Yara’s third and final section, which is called “Rightbirth”—a word-reversal—shall we end by beginning again? In a recent piece for Arcade I wrote about translation and beginnings, and about a period of time in which I couldn’t help but write and rewrite the sentence, “Translation begins in a room.” In what room, and with which tools, does your writing begin?

I find that when it comes to my novels, everything, in a certain way, begins as a free-for-all. Uncontained, undifferentiated, no room. It’s a miracle that it ever sort of comes to be with a beginning and an end, you know? I’ve heard it said that novelists kind of have to reinvent the wheel each time. I think it’s really all about returning—I mean, continuing to return to the work, to the file where the writing is, even if there’s resistance, even if I don’t want to. And of course sometimes I really don’t want to. It’s about going back to it and working with the malleable substance that language is. I feel language is totally malleable, so I try to approach it as a visual artist would—going to the studio, showing up, and continuing to work with your materials. If you keep going back, usually you do get somewhere.