Designing for What Isn’t There

Theatre designer Teresa Przyblski on creating an environment for William Kentridge’s film series Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot, where immersion begins with restraint.

For its current exhibition of William Kentridge’s film series Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot, Koffler Arts turned to Toronto-based theatre designer Teresa Przybylski to create the perfect environment for presenting the prolific South African artist’s insights into his creative process. (Previously on Arcade, we featured a conversation between Kentridge and former CBC Radio host Eleanor Wachtel, also presented by Koffler Arts.)

The Poland-born Przybylski is best known for her evocative but often minimalist work across theatre, opera, film, and dance. The winner of five Dora Mavor Moore Awards and two Geminis, Przybylski has collaborated with many of Canada’s leading companies and directors, bringing a sharp visual intelligence and a finely tuned sense of environment to each production. Her designs often balance bold conceptual ideas with meticulous attention to detail, creating worlds that are at once expressive, playful, and deeply responsive to performance. She also taught theatre design at York University.

Arcade spoke with Przybylski about the philosophy behind her approach to theatre design, her personal interest in Kentridge’s work, and the true meaning of an “immersive environment.”

Do you remember your first encounter with William Kentridge’s work?

Yes, around 20 years ago when a friend took me to an exhibition of William Kentridge in Milan. I didn’t know much about him at that point, but I’d heard of him. The main focus of the exhibition was his film Play the Dance, which is a series of vignettes of people walking. I’ve seen the film presented differently in other places, but in Milan you stood in the centre while the film was projected all around us. You were inside this panoramic film of people walking, with only a small break through which visitors could enter and exit. The rest of the exhibition mostly displayed the props and other elements Kentridge used to create the movie.

There is a fantastic explanation of the project and representation of his process on the Kentridge Studio website. The Kentridge Studio website is probably one of the best websites I’ve seen for any artist. Kentridge’s work is presented in so much depth. Explanations of his projects that go deep, especially when he talks about his process, was the most significant encounter on that website when I was doing my research.

When I think back to Play the Dance in Milan, I remember what it was like being in that room with this movie, how carefully Kentridge picked the music, and the pleasure of watching something that is so well done. The quality of it doesn’t feel in any way enhanced by technology. It feels pure: the very simple means of how he did it, using simple cameras and studio lights. It’s very theatrical, of course, but it’s not an animation of AI proportions, it’s just a real thing and you feel it, you connect with him very directly.

It’s interesting you bring up technology and AI, because I suppose it’s true of any theatre designer, that the work is about creating immersive environments—something that Kentridge has always been exceptionally good at. Today, the idea of immersive environments is very much associated with the digital world, which is quite a different, more synthetic thing. But Kendrick has always stayed true to this idea of not allowing the technology to overwhelm things.

Yes, absolutely. Obviously, he’s still using the means at hand, and he’s using a camera, and of course with the film, we have in the gallery, there’s the special effect where there’s a double image of him onscreen, and all kinds of other things. He has fun with it, he’s still in control and he’s the one pushing the buttons if there are any buttons to push.

My understanding of his work is that he became famous quite late. He was not very well known in his 30s or even 40s. And then one gallery asked him for some work and he sent his sketches as well as a little movie showing how he made those sketches in sections and added things one layer at a time. The gallery said, “Yes, that’s great!” But they didn’t want his art, they just wanted the movie. This animation of his art-making appealed to the fascination we have with process, and getting a glimpse into the artist’s brain, helped make Kentridge’s art accessible and admired.

Artists can have this rigid idea of who they are, what they want to achieve, and what they are working towards. Sometimes they’re successful and sometimes they are not. But Kentridge always seemed to follow what his own art was telling him, changing and exploring.

What was your reaction when you were asked to design this exhibition?

I am a big admirer of [Koffler Arts General Director] Matthew Jocelyn from his time as artistic director of Canadian Stage. He was one of the few directors who brought interesting, international projects here. I believe Matthew likes my minimalistic approach to design. Sometimes people think set design is a craft, but I feel you have to have some concept and artistic sensitivity. It seems like I was a good fit because of the theatre background and we have already worked really well together before.

We bounced ideas around and checked those ideas with the Kentridge Studio in Johannesburg. So it was a journey between the three. I grasped Matthew’s concept from the beginning, that it has to be a space that brings forward the personality of Kentridge, but also be a place where people can come, sit, have coffee, and watch or not watch the movie.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail many years ago, you said that when it comes to theatre, you prefer not to call them sets but environments. Could you take us through your thinking?

I love talking about it. How much time do we have? Many years ago, I was designing a production in Toronto that had some components of Indian culture, and we had a specialist in Indian theatre working with us. He told us that in India there are several words to describe the relationship between audience and the performer. There is one word describing the energy flowing from performer to the audience, and there is a different word describing energy flowing from the audience to the performer. And there is another word that describes how those energies meet. In English you hardly have any words for that idea of energy flowing in the theatre, it’s just “energy.”

That was an interesting realization, where the person viewing has the satisfaction of participating mentally in the performance. Let’s say you create a space that is a realistic room, maybe it gives the audience a clear sense of the space. But there is nothing left for the audience to imagine, nothing that lets them use their brains to fill in the gaps.

Chekhov was the biggest master of that concept. When you watch his plays, you know that it’s more important for us to watch people who are not saying anything. So how do you create the same effect in design? If you call it a set, then it doesn’t make sense. I just call it an environment. That tells everybody it’s not a finished product and it doesn’t exist without those three elements—audience, performer, and the energies that flow between them.

Sometimes it’s not easy and it happens in a very mysterious way. I could tell you, “This is a castle,” and say it once or twice and suddenly you start to imagine a castle. That’s my concept for an environment, to engage people so they feel like they are participating in the creation of the world on stage.

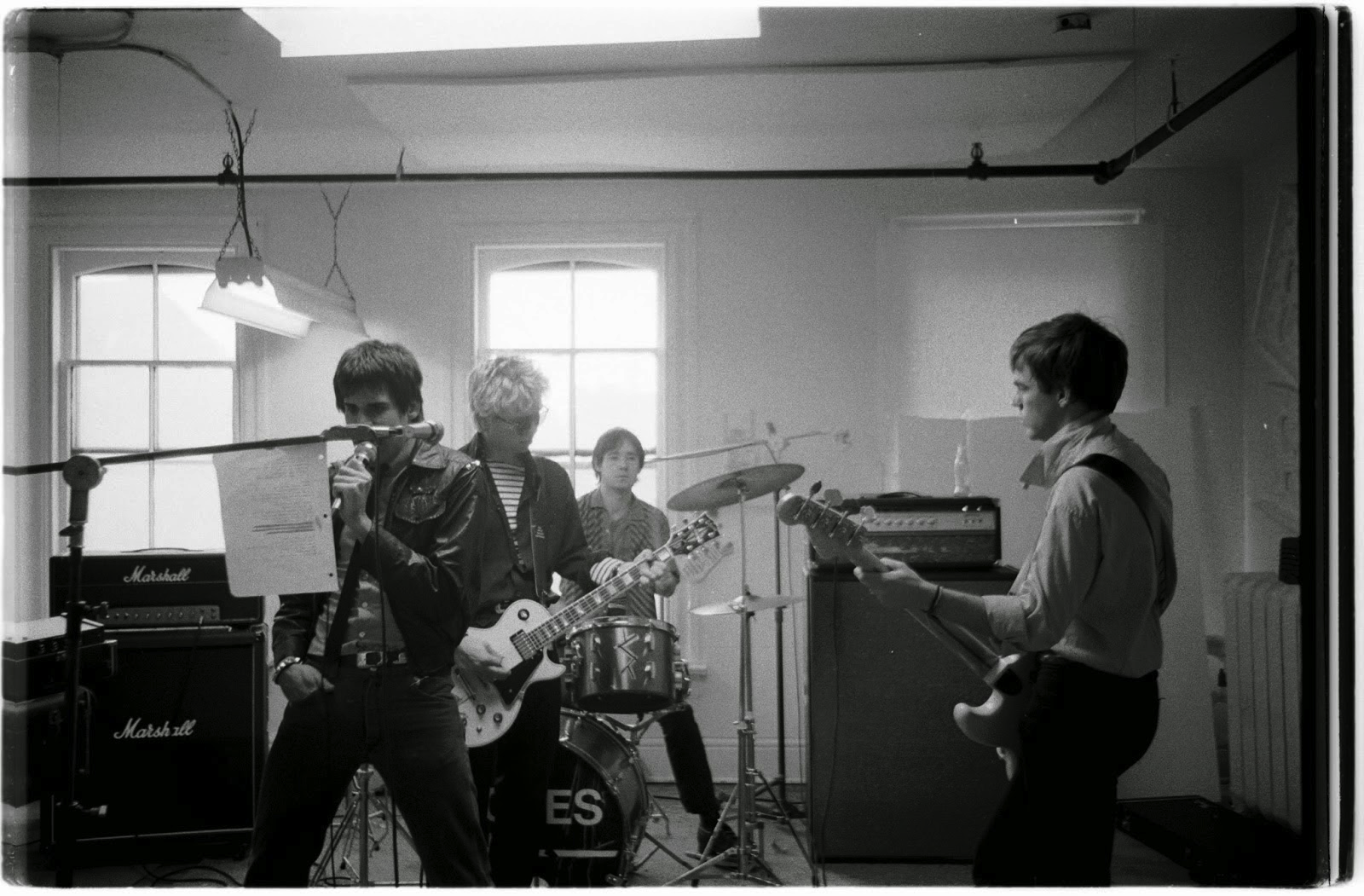

Details from Przybylski’s design for the Kentridge exhibition. (Photos: Henry Chan)

You did all of your training in Poland, where you grew up—and you actually studied architecture and engineering before moving into scenography. What impression did your education leave on you?

Yes, I’m an architect, an engineer, I can build bridges… I’m joking about the bridges. In Poland you have to have an engineering degree to finish architecture school. So yes, I have that architectural understanding of space. I was talking to someone recently about our education, and in a strange way that school and our Communist-era education, which could be considered quite closed and behind walls, somehow gave us license to think big, and that we could change the world.

What was actually great in our education or upbringing is that we had to find the truth. You had to dig for it. It wasn’t available, the truth was hidden somewhere. That’s an interesting process for an artist, when you have to separate bullshit from something that is meaningful. Sometimes the conditions that generate rebellion are good for your future work.

William Kentridge’s film series Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot runs in the main gallery at Koffler Arts until March 8, 2026. (See screening schedule.)