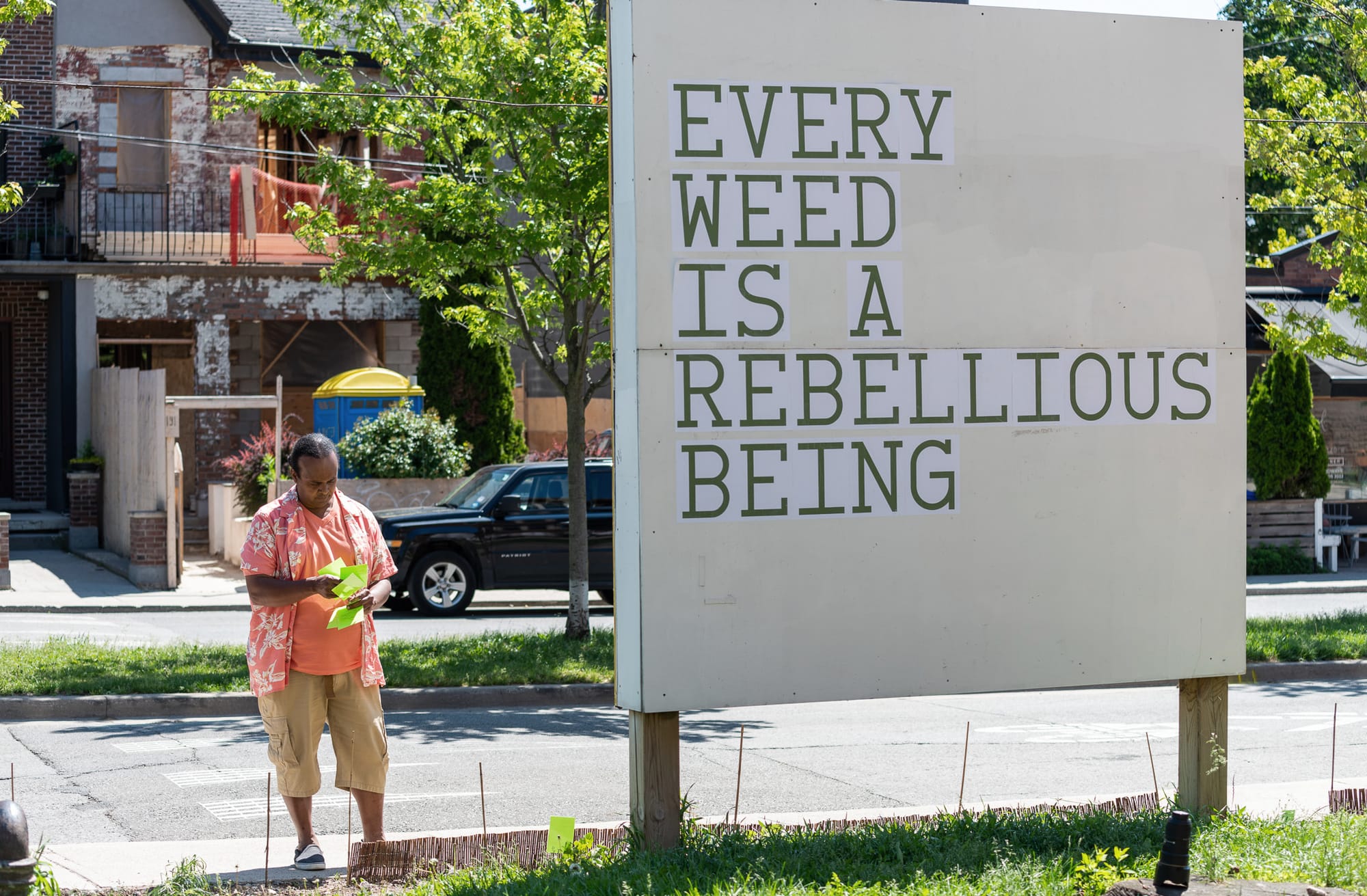

Every Weed Is a Rebellious Being

Though the original names of many native plants in Canada were lost to colonialism, with the garden he has designed in dialogue with the exhibition Botannica Tirannica, Isaac Crosby aims to show the resilience of both Indigenous knowledge and the plants themselves.

A short while ago, it was such a sad looking patch of ground you probably wouldn’t have noticed it was there. A common area gone fallow and forgotten near the entrance of the Youngplace building on Shaw Street, any trace of actual soil buried under more than half a foot of dense clay and gravel. The sort of disused, in-between space, barren from neglect, common to most cities.

Now a garden grows, thanks to the intervention of Isaac Crosby, the Black-Ojibwa agricultural expert and plant knowledge keeper who was commissioned to design a “Garden of Resilience” in dialogue with the exhibition Botannica Tirannica at Koffler Arts. Created by the São Paulo-based artist Giselle Beiguelman and originally shown in Brazil, Botanncia Tirannica explores the interwoven histories of botany, taxonomy, and colonialism, such as how derogatory references to marginalized peoples became encoded in common plant names, and Indigenous plant and agricultural knowledge faced systematic erasure.

In preparation for planting, Crosby consulted with Beiguelman on how to adapt ideas from the show for a local context. Beiguelman says she was surprised by what she learned from her conversations with Crosby, along with Jonathan Ferrier, an Anishinaabe scientist and biology professor at Dalhousie University, who advised her on the Canadian version of the show. As she points out in her interview with Arcade, unlike in Brazil, where many plants are still called by their Indigenous names, like jacaranda and îpe, in Canada “Indigenous knowledge was largely erased from the popular naming of plants.” Meanwhile, “[cultural] appropriation was a means of transforming the cultural symbols of Indigenous populations into national symbols.”

Crosby, who also goes by Brother Nature, gave Arcade a walk through of the garden as he was applying the final touches before the official opening of Botannica Tirannica. Ironically, while in the midst of transforming that depressing patch of ground—a process that required extensive resoiling—a passing neighbour stopped to tell Crosby that the tree stump in the middle of the garden was, once upon a time, a ceremonial planting by Queen Elizabeth.

ISAAC CROSBY: The Garden of Resilience is meant to showcase the resilience that native plants have shown to this day, but also how the names of those native plants were changed through colonization. There will be tags providing the Latin name, the derogatory English name, along with the actual native name for the plant. Hopefully people will take away what some of these plants were originally called, but you can see here some of the derogatory names, like the smokebush, which is also known as a “dusky maiden” in reference to Black women. When it’s flowering the leaves are purple, but right now you can see it has this haze that’s like smoke. I’m like, how is that a dusky Black woman? How does that work?

When I went back to school at 40 to study landscaping and horticulture at Humber College, I remember thinking, “Do we have to call it the wandering Jew, can’t we just call it the wanderer?” Some people now want to call it the “wandering dude.” I’m like, what the heck, so people sort of still get to say it?

Over here we have a Dieffenbachia plant, commonly known as dumb cane. I was telling Giselle that plants that are native to Brazil are often houseplants to us. Here they would probably die outside in winter time. But Dieffenbachia has an interesting story. My family are descendants of both African slaves and Indigenous people, and I remember hearing from my grandmother how if a slave was acting up they were forced to chew the leaves from this plant. And it would make their mouths swell up so they couldn’t speak. It made them “dumb.” I learned from Giselle that they did the same thing with dumb cane on slaves in Brazil.

And the tansy, or Tanacetum vulgare, often considered a weed, is another interesting one. Apparently in Brazil, it’s called “Catinga-de-mulata,” which can be translated as “stinky black girl.” Where did that come from? Some scholars say it was used in the funeral rituals of enslaved Africans, where they would rub it all over the bodies of their dead, the smell of its perfume meant to help them pass into the next life. Somehow the Brazilian slave masters came up with “Oh, that’s a Black girl smell.” They took this beautiful, ritualistic idea and turned it into a racist trope.

All of these common English names we have for plants, there are Indigenous names that predate them by thousands of years. But when settlers came over here, maybe those names were too hard to pronounce, so “We’ll call it this…” Okay, but that’s not the plant. The Indigenous names will tell you what that plant is actually used for, as food and our medicine. The Latin or common names won’t tell you where the plant’s from, or what it’s actually good for.

When I started designing the garden, it was suggested that we have a pathway cutting straight across. But I thought let’s do something different. Colonization never ever happens in a straight line. It curves, it bends, it twists. So I thought of the route through the garden as a pathway of colonization. As you walk along it you see more non-Indigenous plants, as colonization starts happening. You’ll see plants like Dieffenbachia or the wandering Jew plant—which, I really hate that name—and the night-blooming jessamine plant, which is called “Queen of the night” or “Lady of the night” in reference to sex workers.

In my culture, Black–Indigenous culture, these plants are all alive. They’re sentient. They’re not foreign to us or outside from us. They’re part of us. In our history, plants came before humans. They’re here to take care of us, and we’re here to take care of them. So when I walk in any kind of garden I always have that in my brain, that these are sentient beings. And if I treat them well, they will grow healthy and bountiful for me.

When it comes to documentation of native plants, each tribe, each nation will have their own stories of where the plants come from and why they’re here. Like the sugar maple, it’s another food source. The sugar maple keys, which we call helicopters, those are edible. And so are the leaves. But people don’t know that. All they know about is maple syrup. Which is fine, but the plant has other uses as well.

My ancestors learned how to farm this land from combining their African heritage and Indigenous knowledge. They got a double dose of how to care for this land. But these days you see Black farmers struggling—while more of them seem to be coming forward, at the same time more are losing their land. Indigenous agriculture techniques are holding on. My people were kicked off our reserves and settled on what is swampland to this day. I grew up on what was our farm, our homestead. It was only later when I moved to Toronto that I realized people who were born on reserves didn't grow up with farming knowledge or garden knowledge. They grew up with whatever knowledge the government was giving them.

That’s why for the past seven years I’ve been a mentor to seven Indigenous youth, teaching them all these ways of farming that they or families have lost. My whole goal is that maybe one day, when they move out of Toronto, they’ll take that knowledge and bring it back to the reserve. I make sure I teach them about things like pawpaw trees, all of our traditional foods that we use or do not use anymore. I'll find the seeds just to make sure that they have that base knowledge. And from there, they can do whatever they want with it.

I also make sure I teach it to non-Indigenous people. Because as I always say, how dare we as Indigenous people expect non-Indigenous people to take care of this land and the garden during climate change if we don’t teach them what we’ve been doing for thousands of years.