Heartbreak at High Speed

How improvised roadside memorials, like the colourful descansos studded across New Mexico, represent more than just the people we’ve lost.

I recently drove more than 4,000 kilometres from my former home in Buxton, Maine to my new place in New Mexico. It was high summer when we left, so we didn’t take the straightest route (which would have been Route 66) but what I took to calling “the high road.” I drove, mainly, logging hours behind the wheel as we churned westward through Ohio, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, then south, through Colorado, down to Taos, finally into Santa Fe. As I drove, the wind turbines of Iowa turned into the fire-and-brimstone billboards of Nebraska. Eventually, my peripheral vision started logging something new. It was the presence of small crosses, painted white, covered in plastic flowers, miniature memorials to a life now lost.

These handmade tributes exist around the world; they’re not just a New Mexico thing. The first time I recall seeing this type of mourning practice was after Princess Diana passed. I was a kid, but I remember the newsreel slowly panning over the thousands of flowers, the hundreds of notes and pictures, all those petals and paper and plastic, heaped by the side of the road in Paris. The tribute at Kensington Palace was even more garish, piled high with overstuffed teddy bears and every-coloured cellophane, yet still moving. She was a beautiful young mother who died a tragic, senseless, ordinary death, unbuckled in an automobile. She meant so much to the world, and so the people mourned.

There is always someone, somewhere, mourning. We only die once, but most of us will live to mourn many times. The luckiest among us will grieve infrequently. In many ways, it is a privilege to walk that dark tunnel. The pain is there because we loved.

Is it love that compels the creation of roadside memorials? It must be, to some extent, about love. But that wouldn’t explain why there are so many of them in New Mexico and so few of them in New England, for just as many people love here as they do there, and just as intensely. People are the same the world over, and our emotions follow the same rough courses. But how we display them, how we make them legible, that’s subject to change. That’s dictated by culture.

According to folklorist Sylvia Ann Grider, author of “Roadside Crosses: Vestiges of Colonial Spain in Contemporary New Mexico” (an essay published in tandem with a series of photographs by Joan Alessi, exhibited at the Albuquerque Museum in 2007), the practice of making and erecting descansos began over 400 years ago. The word comes from the Spanish descansar, meaning “to rest.” Initially, these crosses were placed at sites where a burial procession would stop, and the pallbearers could set down their burden. It was believed that an unburied corpse was at risk, the soul in a liminal state, so the crosses served as supernatural protection against sorcery or demonic influence.

Over the centuries, and with the advent of American car culture, the roadside crosses began to serve a different function. The memorials began springing up where “the deceased drew the last breath on unsanctified ground, without the last rights of the church.” They were still protective, meant to help the untethered soul escape purgatorial banishment, but they were no longer used for those who died of natural causes. They became solely reserved for crash victims—people who died in bloody, fiery, high-speed disasters. A most hellish way to exit the earth.

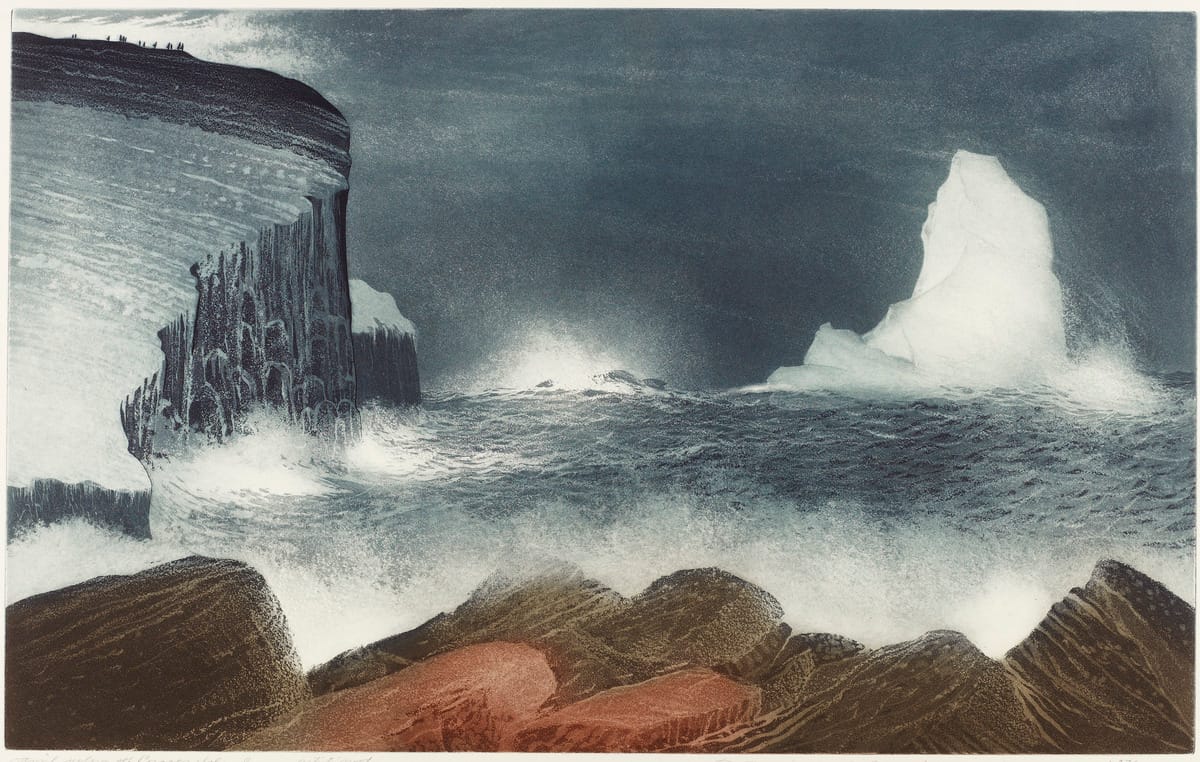

A descanso in Talpa, New Mexico. At right, a roadside memorial in Wyoming marking the place where runners were killed by a driver. (Images: Carol Highsmith/US Library of Congress; Greg Younger/Flickr)

You can now find roadside memorials in nearly every part of the world. Until recently, I didn’t really think about them, save to feel a small pang of sadness whenever I spotted a laminated picture of a smiling teenage face. While many of the markers I saw in New England and Canada were made from plastic flowers nailed to plastic crosses, surrounding a single image of the deceased, those that populate the New Mexico landscape are more varied. Some are topped with pounded tin lunettes, some feature delicate straw inlay that shines like gold, some have carved rosettes or fleur de lis, some even have wooden statues accompanying the cross (bultos). Alessi’s photographs document a wide range of creative decisions, from elaborately framed ironwork crosses with enamel flowers to hand-painted wooden crosses topped with hardhats, frisbees, and teddy bears. Some are surrounded by beer bottles, others have angel figurines and Christmas ornaments. They’re all heartbreaking in their own way.

I’ve come to read these tributes two different ways, and whether I feel the nausea-inducing contagion of grief depends on which road I chose that day. In one lane, descansos are forms of art, a way of punctuating the sameness of the pink desert with temporary tombstones. Instead of designating the presence of a decomposing body, the crosses signal a different sort of decay—that of paper, plastic, paint, and metal. Man-made materials, humble and cheap, from a distance can appear lovely beyond belief, as elegantly arranged as a Flemish still-life.

Folklorist and professor Henry Glassie has written persuasively against the distinction between “fine art” and “folk art.” However, he conceded that so-called “folk art” tends to speak differently to viewers than works by Old Masters. These works are less about the individual maker and more about the expression of shared values and emotions. “People living in intense communication will orient to certain modes of performance and suffuse them so with emotion and meaning that they roll the collective soul open for contemplation,” he writes in The Spirit of Folk Art. “Art is what is best, deepest, and richest in every culture.” Decorated with traditional Southwestern motifs, these monuments aren’t just for the person who died. They’re for the driver, who gets a sideways glimpse into the rich, deep lives of locals.

The other way of seeing these monuments is as semi-permanent manifestations of human pain, as impossible to erase as the knotty twists of scar tissue that rope around a mangled limb. The deceased is remembered with certain symbols—the hardhat, the roses, the beer cans, the horse figurine—objects that attempt to speak to the complexity of a life cut short. The grief becomes sublimated and totemized, because the loss is worth the effort. That singular life had weight; their death left a vacuum.

It doesn’t matter which reading is correct. Either way, these sometimes janky, sometimes lovely, (and often distracting) memorials are suffused with meaning. They are mundane and cosmic, communal and individual. They symbolize the worst pain—and the very best of us.