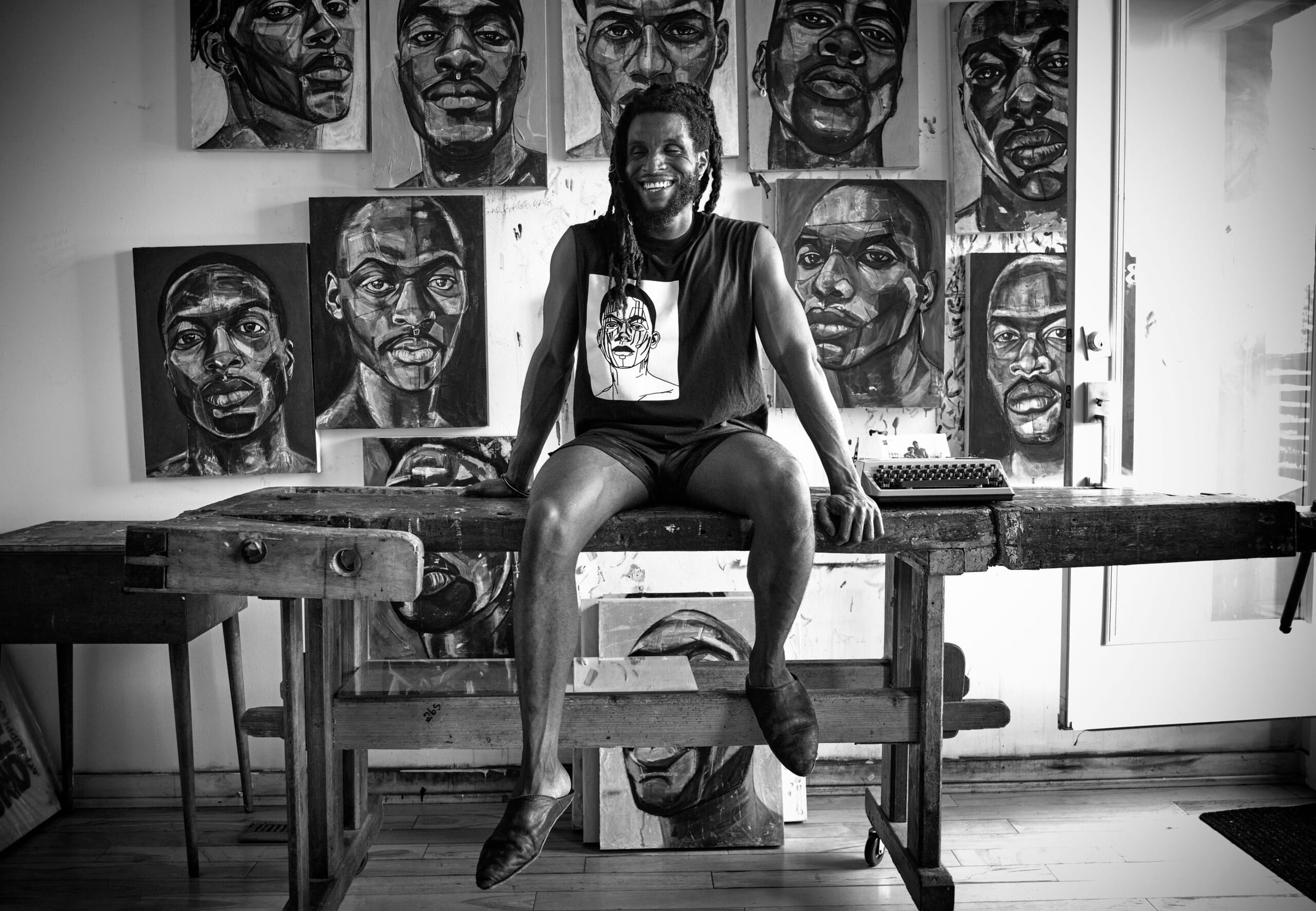

Paring Down to the Essence of Portraiture

Photographer Dimitri Levanoff on his exhibition “BEING THERE: Portraits of the Toronto Art Community” and the draw of the artist as subject.

On November 2, photographer Dimitri Levanoff sat down with curator David Liss to discuss the ideas, methodology, and motivations behind BEING THERE, his ongoing portraiture series featuring an impressive cross-section of Toronto-based visual artists, gallerists, and curators—some of whom Levanoff has worked with through Imagefoundry, the bespoke printmaking studio he operates. A selection of 21 images from the series—curated by Liss and including portraits of artists Margaux Williamson, Micah Lexier, and Rajni Perera—is now on exhibition in Koffler301, the new gallery space at Koffler Arts.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation. BEING THERE runs until December 14 at Koffler Arts.

Why did you begin this series?

Like most things, it has multiple roots, starting with the fact that I’ve been interested in portraiture all my life. I’ve been photographing since I was a kid, more or less, and the subject that interested me the most was people. I was always drawn to faces, I was always the people watcher. Wherever I go, especially when I travel, I look at people. Something about seeing others attracts me greatly. So, of course, that was a natural thing for me to go to.

The second tributary which feeds into this river probably would be encountering works which made a huge impression on me. These would include Irving Penn’s portraits, of which there is such a fantastic volume of fantastic work, the quality of the photographs is incredible. Also Richard Avedon’s later work, when he photographed older people, especially people in the arts.

One photograph that tripped me specifically was of Francis Bacon in his London studio by Jacques Saraben. Bacon had been photographed a lot in that studio, which was always a great mess, I think he was there for at least a decade. Here, Bacon is standing, wearing this black turtleneck and spotless pants. He looks maybe sheepish or unsure of himself against the background of this studio, which just looks like a disaster, piles of brushes, squeezed out tubes, things like that. There was something about that shot which just grabbed me so much that I wanted to make work like that.

You started working more in this vein just before the pandemic, wasn’t it, when you were taking portraits of small business owners?

That was the immediate stage prior to this body of work. All through the 2010s I was experimenting with tools and specific techniques. I tried multiple formats—I went large format, medium format, I photographed on digital platforms, I photographed on analog film. I tried to print images in analog ways, like using darkroom work on platinum or palladium prints, salt paper prints, and that type of thing. So I was kind of in search mode looking for the tool set that would get me closer to where I wanted to be.

Then in 2019, the guy I consider my mentor and friend, Geoffrey James, sold me his old Leica. It was a black and white monochrome Leica, which I had never worked with before. There were quite a few things about it that I was not familiar with, specifically because it’s an older model and it creates such undercooked, half-baked pictures that it leaves a lot of work to be done in post-production.

Slowly I started to get somewhere I wanted to be. When the pandemic started, suddenly everyone had a lot of time, so I went around the neighborhood and started to photograph local shop owners. It was such an interesting subject because people were trying to keep up a brave front, but everyone was really hurting.

That set of images was called COVID Blues. That’s when I learned how to shoot with that camera, how to process the images, and get to the point where I was somewhat happy with the results. There is a particular shot in that set of Joe and Grace, the owners of a hair salon, which finally nailed it. Like something about that shot was doing all the right things.

I felt that I had found the formula and I wanted to apply that formula to whatever would come after. And what would come after is photographing the artists I have worked with. Why artists? Because for me, this work has a deep emotional meaning. And I find that people in arts specifically, that’s what they do for a living, right? They dive into these emotional depths and try to bring something back to put on the wall. The artist as a subject, as a group of subjects—that’s where I needed to go.

What about the choice of black and white? Because, especially with some of the artists here, their work is often very colorful. And you don’t shoot in black and white exclusively.

Far from it. There is a lot of colour work in my portfolio, but for portraiture I feel that stripping away colour helps. It really zooms you in on the things which are essential. I mean, almost all of us look kind of about the same shade of tone, from slightly darker to slightly lighter, but humans are humans. So getting rid of colour with portraiture is a power move in a way that really lets you focus on things that are more important.

Which things are those?

That’s a tricky question, and the answer can be as extensive as you want or pretty short. Because once you unpack it, what is it you’re asking about? It’s what is that essence I’m trying to capture. It’s not the gaze necessarily because not all of the people are looking into the camera. I’m looking for something which you can call an iconic quality. And the word icon I’m using here is not in the sense of an archetype, but more of almost a religious object. I’m not religious, but I do recognize the quality which is present in this type of work. It might be a religious object, an object of veneration. So this is the quality I’m going for, using black and white pares things down, gets you closer there.

I wonder how your photo shoots work. For example, your subjects don’t look overly posed.

That’s by design. Again, there’s multiple layers to this. First, I try not to overprepare. Generally, I already know who I’m going to be photographing and I have a general idea about what would be the best angle to present someone. I don’t really want to beautify my subjects, but I do want to make them look in a way that they can identify with, or at least with how I see them.

The second part is that it’s probably pointless to go past a half-hour or 40 minutes because the energy starts to flag and you just don’t get what you want. Generally, when you plan to shoot someone you want to be done within an hour, because at around 45 minutes you start seeing a glaze come over the person’s face. It’s almost always that the shots I chose for production are from the last few shots, because at the beginning there is a certain awkwardness, we’re just finding each other in that space.

And this series with artists is ongoing, isn’t it?

I think I’m gonna keep on doing it until I drop. Here I should say some thank-yous to the team at Koffler Arts, because they made this show so effortless and easy. Working with the team was absolutely fantastic. But I should say that when Koffler approached me I was apprehensive, because for me this project was meant as a time capsule. I wanted it to be something that stays under the radar until later. You know, 15 or 20 years from now when we are wrinkled and old, we can look at these pictures and we feel good about it. But there is more to it as well. I feel that the times are changing so rapidly, clearly we are going through such big changes in terms of, well, everything really. I feel compelled to try to record as much of this time as I can with the tools that I have, which is portraits of people I know, people I work with.