The Artist’s Mind is Their True Studio

In a conversation with Eleanor Wachtel presented by Koffler Arts and the Canadian Opera Company, William Kentridge discusses a career marked by indeterminacy, shadows, and restless energy, where drawing is at the heart of his work.

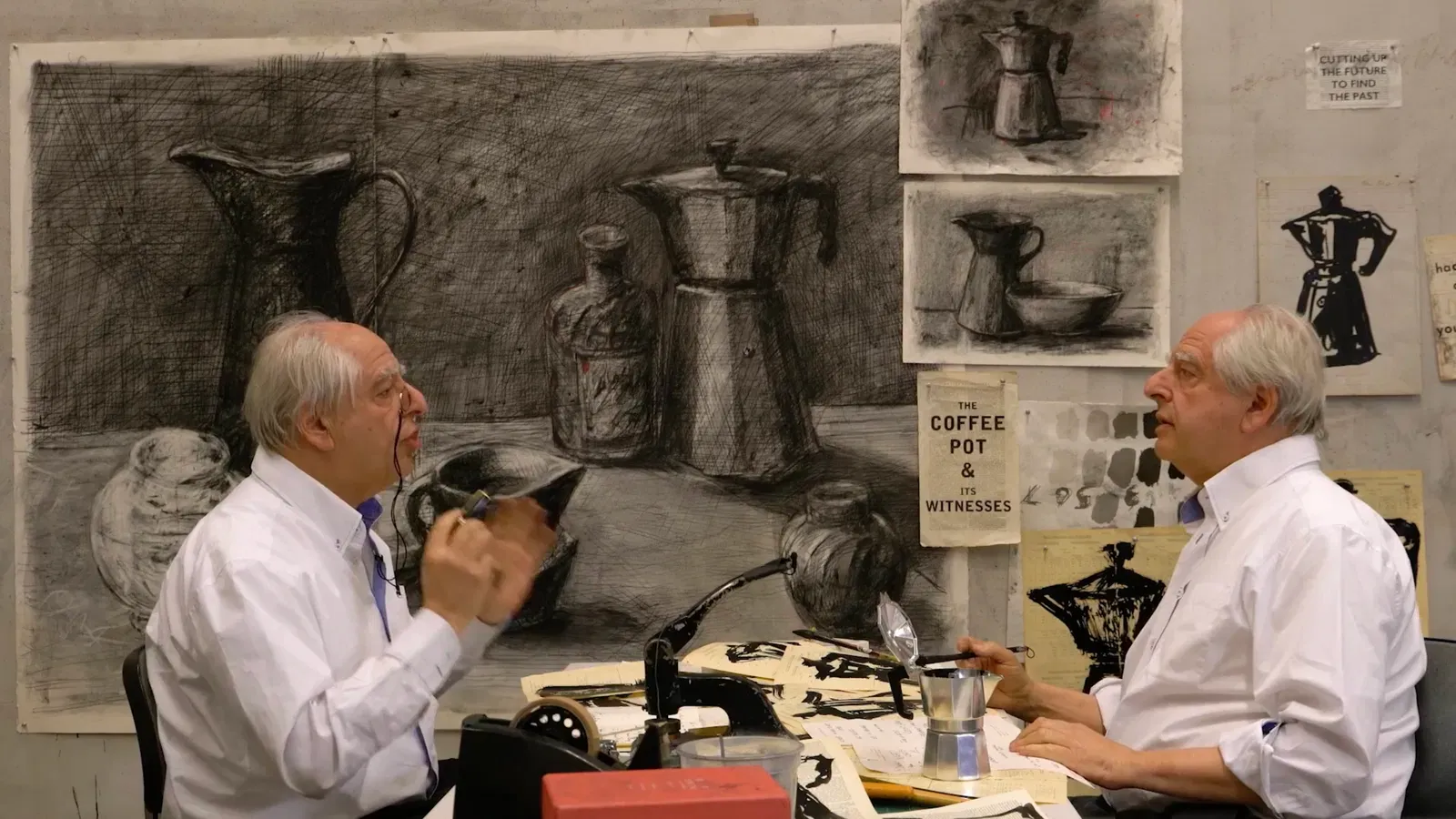

During the pandemic William Kentridge began working on what would eventually become Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot, a series of 30-minute films the South African artist later described to The New York Times as being “very much about giving a sense of the incoherent ways one’s mind works when making things.” Over the course of its nine episodes, shot entirely in Kentridge’s Johannesburg studio, that incoherence is pushed to playful, even dadaist extremes, with two versions of the artist frequently appearing in the same frame, contradicting and arguing with each other.

But across a career that has spanned drawing, film, installations, painting, and opera—as both director and production designer—indeterminacy, and an interest in the mutability of things, have long been at the heart of the 70-year-old artist’s work. Kentridge’s ethos might be best epitomized by his animated films from the 1990s. Working with charcoal drawings, he treated the frame as a kind of palimpsest, photographing the drawings in stages of erasure and redrawing, repeatedly altering a single drawing to suggest movement, thought, and time—but time as always recursive, layered, and burdened with history.

Earlier this year, while Kentridge was in Toronto to direct his interpretation of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck for the Canadian Opera Company, the artist joined former CBC Radio host Eleanor Wachtel for an on-stage conversation presented by Koffler Arts and the COC. The following is an edited transcript of their talk.

You’ve worked in different media, in different art forms—theatre, cinema, opera—but your first love, the form of expression that most suits you, and the starting point for many of these projects, is drawing. It’s the heart of the activity. Why is that?

Partly by default. One understands that in the 1970s, when I was thinking about becoming an artist, to be an artist at that stage essentially meant oil paint on canvas and there would be some drawing. But that was usually a preparatory stage to oil painting, which was to be a real artist. But I was singularly inept at painting in oil, so I was kind of reduced to making drawings.

But the other thing about drawing is we know that all children draw. There are very few children that don’t make a mark picking up things, and somehow it has to do both with the movement of the arm, but it also has to do with making something that is from you, but more than you. So you make your mark, but you step back and “Here mommy, here’s an image I’ve made.”

It’s both connected and has its independent existence. But most children have the good sense to stop drawing when they’re eight or 12. I just forgot to stop. So that’s the other direction into drawing. But the drawing in charcoal particularly, which was the medium that I found in my thirties… I guess that’s when suddenly I could start calling myself an artist and not a technician, not knowing what to write in visa forms and things like that.

And I think with charcoal, it had to do with its changeability, its provisionality. That you can make a charcoal mark and you can wipe it away and erase it very easily and very directly. So it meant that the indeterminate state of a drawing halfway through its making could become the heart of it, rather than just a preliminary thing.

I think it then moved from being what it was to make drawings which you could alter, you could erase and redraw them, to find the right marks, from that into animation, where that adjustment and erasure of the drawing doesn’t have to stop. I suppose the difference between painting and drawing—when I was painting and why I stopped, was that I was always thinking, does this look nice? Does this look good? Looking this way, that way, if I stand back and I half shut my eyes, how’s the painting looking? Whereas with charcoal drawing, it became a medium with which to think, to allow the thoughts to actually happen in the physical making. And that’s an utterly different, utterly different process.

You mentioned that the physicality is essential, as you say, it’s the medium through which the thinking happens. The drawing is a testing of ideas or a slow motion version of thought. How does that work?

Just to take a moment, let’s talk about a static drawing before we get to animation. There’s obviously an initial impulse. There’s an image you vaguely have in your head, or at least say there’s a horizon line. Let’s draw a line. Okay. That becomes a horizon line on the sheet.

We can work with that. But as soon as the first marks are made, it becomes a conversation between the drawing and yourself. You know, what you’re thinking into it and what it’s done. You thought, oh, I’m gonna do a beautiful clean horizon line, but there’s a bump in the middle, and is it going to shift into a rock? Does this actually change into a stage set? What does it become so that it’s not simply pure will on your part, pushing through and insisting on what the image is going to be from this clear image you had in your head, which some artists do. Some artists absolutely start at the top left-hand corner and the drawing is finished when they reach the bottom-right.

But mine has always been a backwards and forwards process of drawing, and that’s when the different ideas start to emerge in the drawing. There may be purely visual ideas, what the drawing becomes, but it becomes a model for thinking about how one can make sense of the world in a broader way of allowing fragments, things from the edges, from the periphery to come in and take a different importance, to understand that it’s always working with fragments and constructing a provisional coherence, a possible coherence, which is natural.

In the studio you see a collage, and you can see that it’s a collage, different pieces stuck together. What’s kind of invisible when you see people in the world is seeing them as collages, which obviously we all are, you know, different images. Our dream, our thought, different fragments, which we present to the world as a coherent self with all the panic behind it.

You’re interested in memory and how it works, and one could say that the processes of remembering and forgetting are enacted in your animation technique itself—something you’ve described as stone age filmmaking, with its layers of drawing and erasure and redrawing. Can you talk about how that form of animation evolved?

When making a drawing, very often you start very loosely and there’s a lot of energy. And if the drawing is going well, the hard thing is to resist slowing down because you’ve got the drawing, it seems to be going well. You don’t want to mess up what you’ve done. So you get more and more cautious, and you start drawing with big sweeps, and then it just becomes from your shoulder, and then just from your elbow, and then just with your hand, and then just with your nothing to try to not mess it up.

So there was often a case of drawings that had started in one way, with a certain energy, dying, dying on you. And so I started saying, let me just have a camera and film the different stages of a drawing being made to see where it dies. It was just an old wind-up 16 millimeter camera, now you could do it on your phone. Just put it into time-lapse setting and it would do the same, the same thing of gradually filming a drawing in the process of being made.

So you start with a white sheet of paper and gradually the forms come into shape over five seconds or 20 seconds. At a certain point I decided, in fact, you don’t have to stop the filming when the drawing is finished, the drawing can keep on going. Each stage can just be provisional rather than final.

It’s one thing to have the drawing coming into being—here’s a landscape, here’s the trees, there’s someone standing, a finished drawing—but you could then keep going and get the person moving and have the tree transform or something shift.

So it came out of recording charcoal drawings. It wasn’t saying, how do I work with animation? What’s a good technique for animation? Let me try ink, let me try conventional cell animation… Oh, I’ve arrived at charcoal. The medium presented itself in advance. The whole technique was kind of there without me having to decide on it.

But what it did show, and this is kind of connected to the idea of the world as collage, or as fragmentation, was that provisionality of a moment. I suppose it was about process rather than fact. That you can draw the tree, the way you take a photograph of the tree and say that’s a fact, that’s a fact in the world, but with the animation, you can very easily take all the leaves off the tree and turn it into a trunk and turn that trunk into a plank and erase that and shift it, and suddenly you’ve got a table and then you can erase the table and turn it into flames and ashes. And you’ve got, in fact, the whole process of what any of these pieces of wooden furniture are.

We take this as a solid fact, but we know it’s actually one moment in a process that started with the tree and will end somewhere in the ozone. So I suppose that the activity of drawing in animation also felt temperamentally very close to my sense of understanding the world as process more than fact. And provisional, not certain.

Shadows are a frequent motif in your work. Not just in your use of black and white, but also large-scale shadow puppets, mechanical sculptures. You had an exhibition not that long ago called In Praise of Shadows, the title of the first of your Norton lectures at Harvard was called “In Praise of Shadows.” What meaning does the shadow hold for you?

Well, just to pinpoint, they’re different. One of them is a reference to the shadows in Plato’s Cave. For him, and for all of us in the 2,000 years of the Western tradition, that’s our Ur-myth of enlightenment, of light dispelling the dark, of knowledge coming with it.

I was intrigued by this founding start, of that myth of these disembodied figures, just the ephemerality of a shadow. But also the fact of a shadow being of us and more than us. I mean, you think of a late afternoon shadow in which you are five-foot-eight becomes 25 feet with a long, low sun projecting your shadow and the speed with which you can move that shadow much faster than you could ever do it yourself.

And the power you sense you have over trying to stamp on a friend’s shadow on the beach, those kinds of games. There’s that strangeness to shadows. I sometimes use them interchangeably with silhouettes, which they’re not.

When we’ve used them in the theatre, we’ve often played with a paradox that if you see a shadow on a screen, as the shadow moves further away from the screen and closer towards the source of light behind the screen, the shadow grows and grows. And as it approaches you, it shrinks. That ability to enlarge a human with a shadow, in a different way.

It also has to do with having to expand from a first image of a very flat two-dimensional image into imagining what the three-dimensional object might be that is causing that shadow. I don’t actually say why I love shadows, but those would be some possible answers.

You’ve said that when you were in high school, you dreamed of becoming an opera conductor. But you couldn’t read music.

Yes, I was told, you know, to be a conductor you have to be able to read music. And I said, oh, I hadn’t thought of that. Okay, let’s recalibrate, not an opera conductor.

Your father loves opera. Is that where you got it from?

I think so. There was always opera being played. When I was a child, we didn’t go to the opera much. There wasn’t so much opera in Johannesburg. But the sound of it was always… and also the sound of it untranslated, because you listen to a gramophone record certainly not following the libretto. So understanding how can something, even if there are specific words, which the singers know, why does it still work, even if I don’t know those words myself, if I can’t hear them. That’s an ongoing question about where is the heart of a song, how much is the words and how much [is] not.

As a person who didn’t understand that, I’m a great advocate for the Roland Barthesian idea that it’s the grain of the song, that’s the heart. And if the singer needs to know the words, it’s a bit like God needs to understand the prayer when you’re praying. But you can mumble the Hebrew without knowing what it means, and that’s going to be okay.

Did you ever consider learning to read music so you could conduct?

I had a year playing the clarinet and I understood I was not going to be a musician. So directing opera kind of is as close as I’m ever going to get to that.

I know it’s heretical to say in this space, but you’re not a mere opera director. You’re an artist working in four dimensions. As you once put it, the opera house says, we’ll give you a canvas, 17 metres wide, 11 metres high, we’ll give you another 18 metres of depth, and then you get to make a two-hour drawing in the space.

But you pour so much more into that space, including everything we’ve been talking about—shadows, processions, animations, projections. Can you say what inspires you to choose a particular opera that’s the right vehicle for work in that way?

Just to expand a bit on that, they don’t just say, here’s the size of canvas, and here’s the two hour duration, and here’s the depth. They also say, choose the people you most like working with. Your set designer, your lighting designer, your assistant directors, your costume designer, your performers, all the people that make it up. It’s an irresistible invitation.

Now, this is talking about existing operas. This is different from operas we make from the ground up, where the text, the story, everything is made new.

But an opera like Wozzeck, where the libretto already exists, the music exists… I find that there needs to be something in the libretto that holds me, usually it’s a theme bigger than the libretto, but which is there. Then, vitally, there also needs to be a visual language with which to think it through.

With Wozzeck, it’s seeing it as a kind of premonition of the First World War. So there’s an image of those Flanders Fields, the western front, which calls to be drawn in charcoal, with the dusty black and whiteness of it. So the form of drawing and the themes start to fit together.

In this particular production, it’s very much the premonition of the First World War. Remember, Georg Büchner’s play was written in the 1830s, about a private in the army who kills his common-law wife. It’s first performed 80 years after his death in about 1915, where Alban Berg sees the production and immediately decides to write an opera about it. He starts writing the opera when he is a soldier in the First World War and finishes it in 1920. So it’s got a big stretch across. On the one hand when Büchner is writing the play, it’s very much about the violence and desperation of poverty, which is its central theme. But then we hear that exacerbated by the cruelty and violence of the commanding officers during the war, or in a military context.

When we were doing Lulu, it had to do with, I suppose, the unstable landing point of desire, that Lulu could never be who her suitors wanted her to be. So we worked with India ink and sheets of paper that were torn up and reconstructed, trying to find the figure of Lulu, or the other people, so that kind of fitted together. It needs that combination of a theme that’s interesting, that’s provocative, and vocabulary to explore it in.