What We Hold Against the Weather

Patrick Pittman on David Blackwood’s lifelong devotion to the stories and storms of Newfoundland—and the fragile work of keeping a place, and its ghosts, from slipping away.

Whatever little you have to your name in a Newfoundland outport, there’s a basic principle always at work—if you don’t tend it, it goes to ruin. As I write, I’m looking out through sub-hurricane gusts of wind at waves breaking over the shore, the weatherboard of my great-grandfather’s house chipping away. Fixing it is a job for the spring. I will, but I told myself the same thing last spring, and I’m beginning to worry I’ve left it too long. When the weather is this wild, in late November, there’s nothing you can do but wait it out. Things return to the elements when you don’t keep them cared for.

To be of here but not of here is a layering of losses, not the least of which is how much you hold on to the right to even call it yours. I left this island as a toddler, floated around the world for decades, checking in only in summers. As my parents and later I moved around, it was my one constant place, but it was never my place. The other day, the woman in the closest grocery store, three towns over, went through the usual routine of telling me how I couldn’t be from here, not with my accent. Why anybody not from here would be in her store, she also wasn’t certain. The strangers in the checkout lines always want to know who my people are. When I name my parents, who both grew up in this village I now sit in, who met each other in the long-closed school I can see across the harbour, they finally let me in. But not without first extracting the cost, by telling me matter-of-factly what they know of me, the thing I try to not spend every moment knowing of myself. “Sure, they both died,” they will say.

And sure, they did.

I sometimes worry that folks like me who leave this place and never stop longing for it tend to romanticize it too much. We keep our connection alive in myth, bound in twine. When it comes to tasks of maintenance, and caring for things so that time and the elements can’t claim them, we understand that we owe something to our ancestors and what they built—even as those who’ve always remained here keep us at a slightly suspicious arm’s length.

The first time I saw a David Blackwood print, I felt something in it I hadn’t felt in any other art of or from the province. In an essay for Newfoundland Quarterly 20 years ago, Lisa Moore wrote about how Blackwood’s work does this to Newfoundlanders; how his gothic intaglios draw you into a place you recognize both in the mundane and the ancient:

“Blackwood's prints felt familiar to me,” she wrote, “the way dreams or nightmares are familiar, made up of things you already know, bits and pieces of the long day, and also some larger, magnificent, sometimes frightening story.”

At 18, Blackwood chose as a teenager to leave the sometimes frightening outport life that would remain the subject of his life’s work. He’d meant to come back, but never really did in any permanent way, though he kept a studio in Wesleyville and remained actively involved with the creative community here over the years. He settled, pretty much for life, in Toronto and its surrounds, ending up in Port Hope where the elites of CanCon are seemingly mandated to gravitate. He is as much a product of the Ontario College of Arts (now OCAD) printmaking studio, which he joined at 18, as he is of Bonavista Bay. And yet the entirety of the work that would see him so bound to the Ontario arts establishment was about caring for and layering on the story that he’d left behind, and building new myths on top of it.

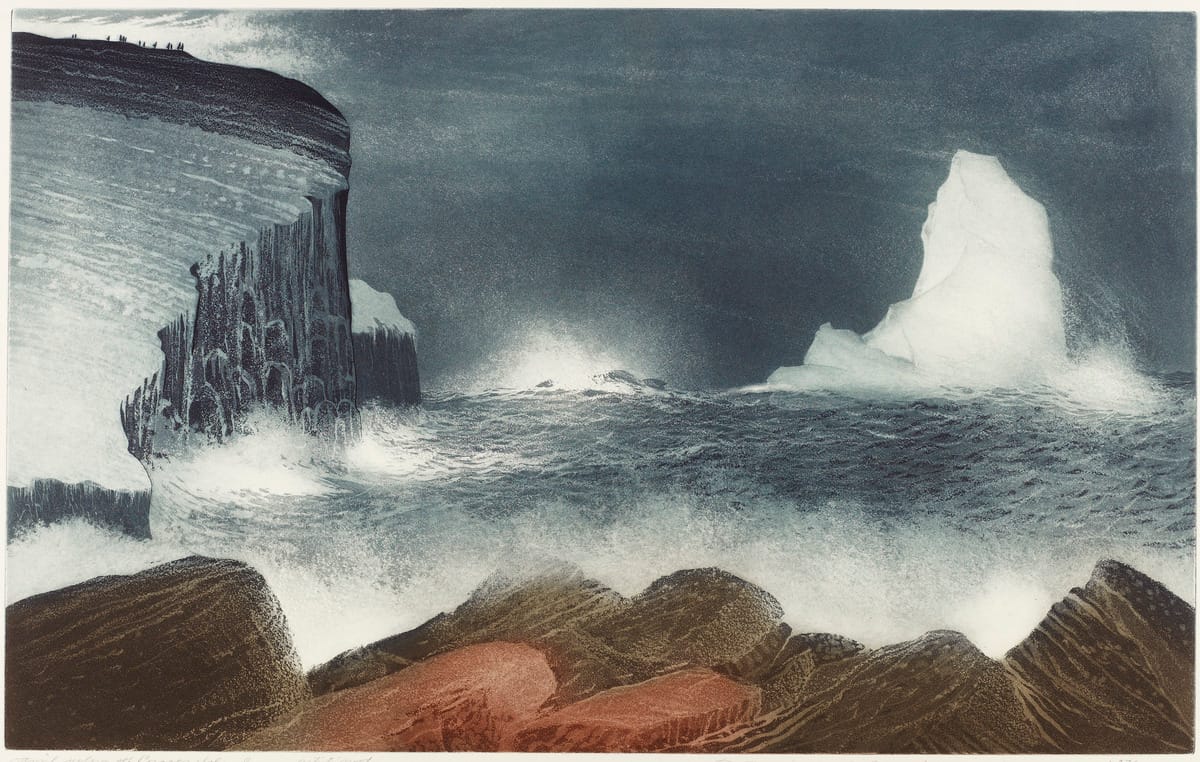

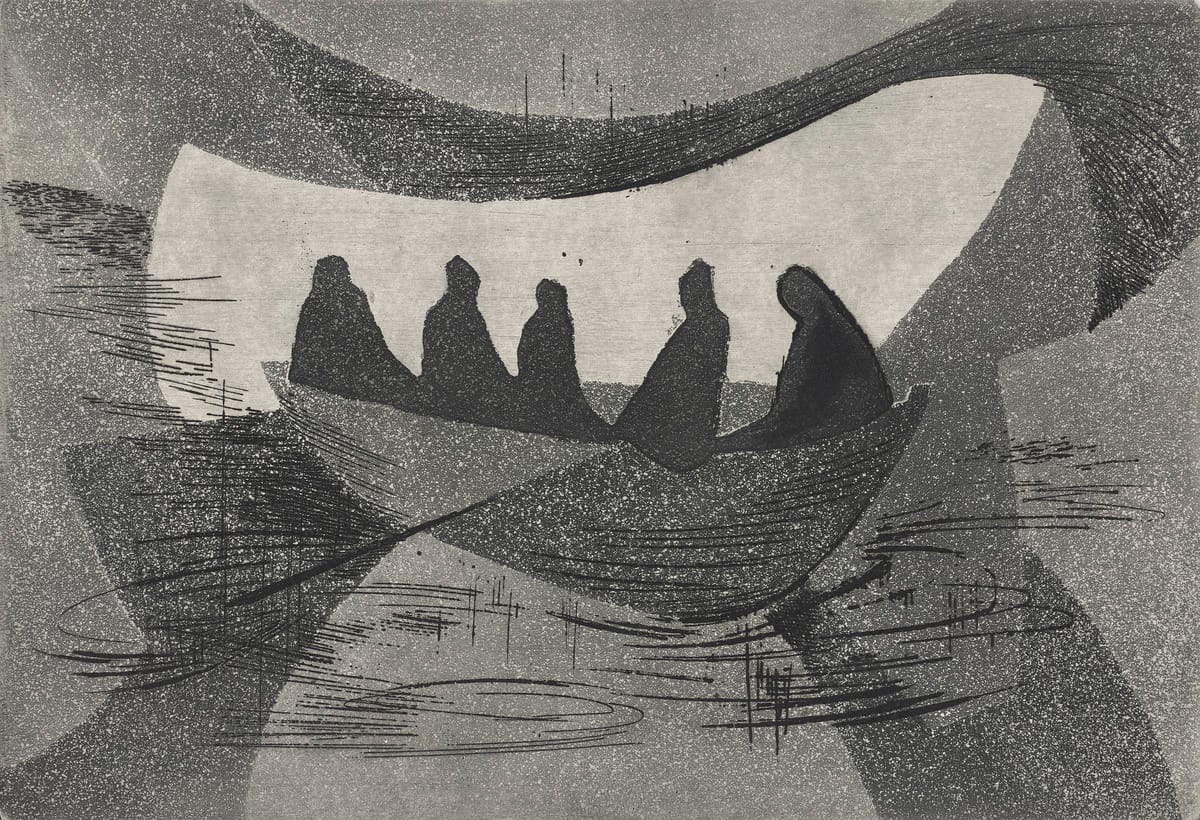

In the most recognizable of his works showing at Myth & Legend—the Art Gallery of Ontario’s current Blackwood retrospective—the Great Lost Party Adrift prints of 1965 and 1971, vast groups of tiny men swarm ant-like atop a monumental iceberg, consumed by the fierce landscape. These prints sit at the heart of the 1973 book Wake of the Great Sealers, Blackwood’s collaboration with writer Farley Mowat, which depicted the wind and salt-whipped life of the sealers of Bragg’s Island, through the lens of the sealing disasters of 1914. The horrors of those men on the ice that year remain one of Newfoundland’s founding myths, invoking not just the ocean and its terrors, but the betrayals of those who worked it by those in power. There are too many figures to count atop that berg, but their collective fate is clear and horrifying. Nothing to do but face it down stoically. In the case of the much smaller five silhouettes adrift in their boat in Survivors (1961), even escape from the horror doesn’t come with relief so much as a recognition of the horror they will bear for the rest of their lives.

But it’s one of the more subtle and less dramatic prints from Great Sealers that best illustrates what I think is the broader point of Blackwood’s work. In Abandoned Ancestors on Bragg’s Island, an oval-shaped portrait of an elderly couple hangs on a wallpapered wall, in one of the rare flashes of colour, however muted, that Blackwood allowed himself (and certainly one of the rare moments when colour isn’t meant to signify impending destruction). The couple pose a little stiffly but not without affection in their early-century Sunday best, while to the right of the picture there is a window with its glass smashed in, and outside a snowy expanse leading to the water. The wallpaper itself is too intact to suggest this home is too long gone. In the distance, the water appears calm, a collapsing wooden fence at its edge, and it’s only if you squint that you notice, either emerging from the water or contemplating it, a small human silhouette—an intrusion of life in this abandoned void. In the Great Sealers book with Mowat, Abandoned Ancestors forms part of the coda, the first of two double-page spreads that close out the story, bringing the scene into the then-present, when the island’s residents had already been resettled to the mainland. In that inscrutable, distant figure is the refusal to abandon things entirely.

As the wall text beside it notes: “The artist felt it was his duty to record and honour Newfoundland, as experienced by his ancestors, by creating art that expressed love and beauty, but also loss, betrayal, and decay.”

It’s that duty, of keeping a promise to yourself to always be on one side of that broken window or the other, but never out of the frame entirely, that is at the heart of it. Blackwood’s is not the smiling land of our provincial song or exported Broadway musicals. It’s a place that puts demands on those from and of here, offering up in return survival until the next day, and a place in the longer story. That’s all the reward we ask for.

There is a vast collection of Blackwood on hand and in storage at the AGO, to which he donated more than 200 prints. (Blackwood served on the AGO’s board of trustees and was named an honorary chair in 2003.) Many of the works included in the exhibition, curated by Alexa Greist, are probably familiar to regular AGO visitors, particularly the prints from the early 1970s, around the time of Great Sealers, which lean most deeply into the tension between the mythic scale of landscape and the lives of those swallowed by it. Same with Fire Down on the Labrador, a 1980 print produced at the height of his celebrity, in which he pushed his sense of myth to its most extreme—expressed in the mismatch of scale between the burning ship on the surface and the impossibly large whale below.

Myth & Legend attempts to differentiate itself from past Blackwood shows by delving at least a little into his process, with ample documentation of his life inside the studio over the years. In an unnecessary but sort-of charming attempt to enliven things, the AGO also commissioned Dr. Melanie McBride of the Aroma Inquiry Lab to produce two custom scents. Visitors are asked to stick their nose in a box and take in the funk of either the Newfoundland coast (saltwater, bladderwrack, and ambergris) or Blackwood’s studio (linseed, Charbonnel intaglio, and fossilized amber). Fortunately, for a Blackwood nerd who’s seen these prints a hundred times, the exhibition serves up an exploration of how his images evolved over the course of their layering—how much of an idea is fixed in its first print, what’s added and refined along the way. Many prints still feature Blackwood’s pencil notes and markup at the edges.

This is laid out through the evolution of Wedding on Deer Island (2020), one of the more ambitious prints of his final years and produced, as all of his work was by then, in collaboration with Janita Wiersma. Though the characters in the initial graphite outlines seem rudimentary, almost nothing changes about them as the work begins to layer and shift through etching and aquatint. The ideas are already firmly in place, but new meaning emerges through the evolution of the image around them. Despite the boat pushing through dense pack ice, this is not another horror—it’s a gathering of men, women, and children sailing under a hodgepodge of flags, on their way to a celebration. In the final iterations, Blackwood allows something striking—the warmth of a lantern at the boat’s prow, glowing red, breaking through the gloom. This was not a journey of suffering but a boat, unlike most of his others, that these people are simply glad to be on.

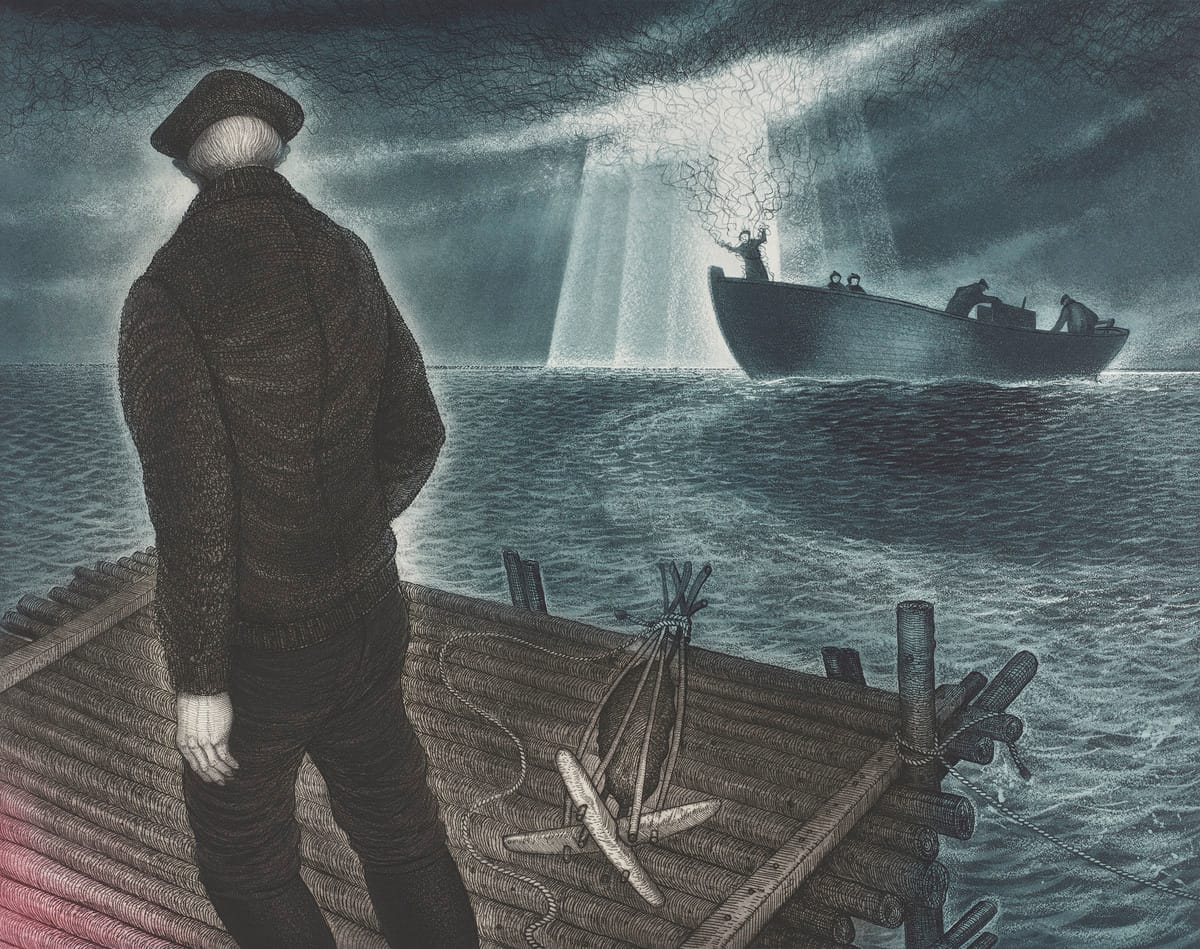

January Visit Home (1975), an image which must in some way be referencing Caspar David Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea, is one of Blackwood’s finest. Friedrich’s early 1800s masterwork was an astoundingly radical expression of communion with the vastness and wildness of nature, and the faith you find out there in the stillness. There’s always been something confronting about its wilful stripping away of all the noise. Forensics have shown that Friedrich originally had that solemn sea full of boats, but painted over them later, finding the work’s solitude through removal of what he first thought he was painting. The figure of the monk at the sea’s edge is not overwhelmed or in fear of what lies beyond; rather, it seems, he’s found a transcendent sort of peace that no other place can offer.

Blackwood’s similarly distant, possibly more secular, subject finds that same transcendence on a different coast. From its title, we know that the subject, like Blackwood, like me, has chosen to stand in this spot to find what it offers. Through the inclusion of several evolving versions of this print, alongside notes to add more frozen vegetation, we see how he began with the certainty of frozen landscape and slowly layered in the subject (the self), from a thin outline to a more distinct form, finding his place in the whole.

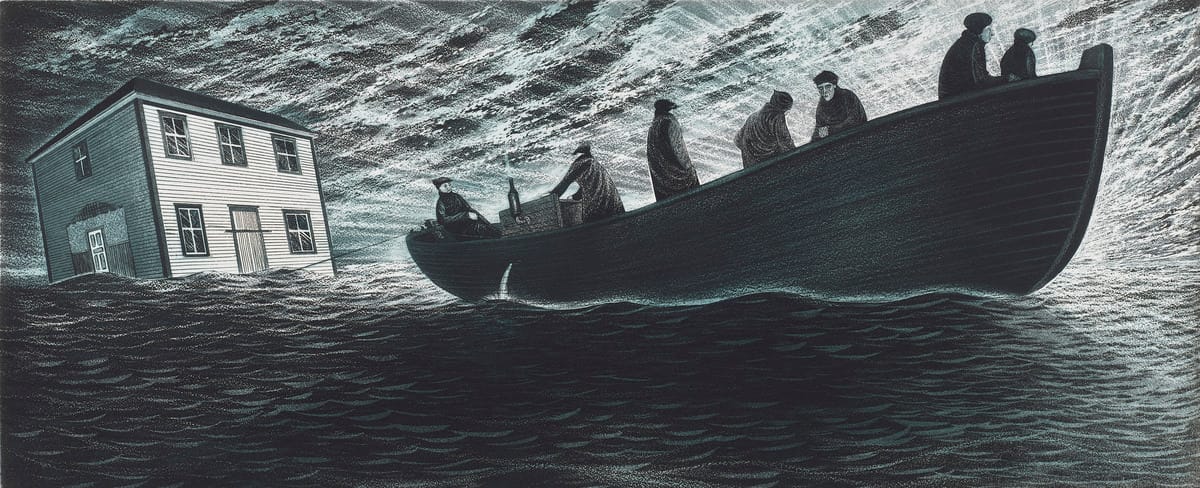

Uncle Eli Glover Moving (1981) captures another foundational moment in the story of Newfoundland. The image of resettlement is so worked over in our folklore and literature that you’d be hard pressed to find a household that doesn’t have at least one image hanging around of a house being dragged over the water, as families were forced to move from their remote outports (largely on islands) to consolidated settlements on the mainland. This isn’t some distant folklore, but from a time contemporary to Blackwood’s own practice—Bragg’s Island was resettled in the 1950s, and the process continued into the early 1970s when the last of the outport islands (including my mother’s) were dragged into the same process.

At this point in his career, Blackwood was beginning to show faces more distinctly. There’s a defiance about what the family in the boat are up to: you can take away our right to have our home where we choose, but you cannot, in fact, take our home. We have six men, a wooden boat, and a make-and-break motor. That’s enough for everything else to come with us.

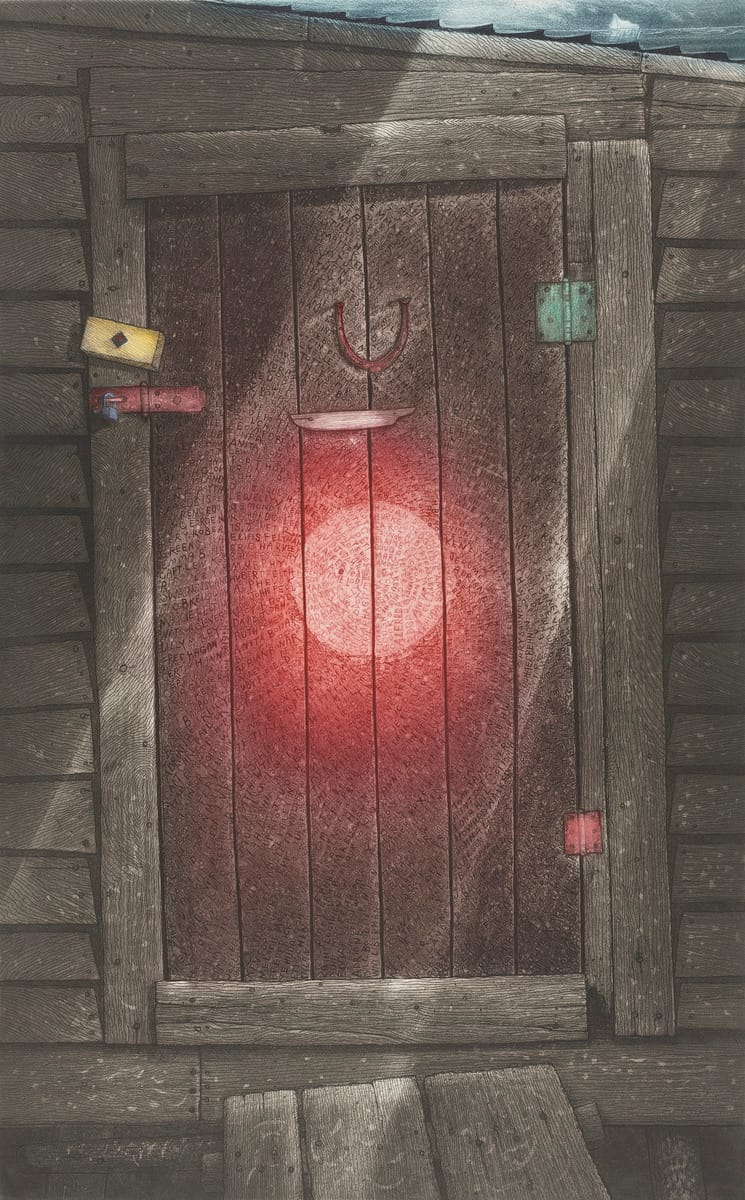

The most intriguing motif to recur in Blackwood’s work focuses on the small improvisations that help make life beautiful here, in spite of the wretchedness of our shorelines. In the 1980s, he produced his first prints based on the shed door belonging to his Wesleyville neighbour Ephraim Kelloway, a scene he would revisit many times until the end of his career. Blackwood told interviewers that as far back as the 1950s he had been observing how Ephraim painted that door, how it constantly changed colours whenever it came time to touch it up. Be it stovepipe paint or pink from a girl’s bedroom, Ephraim used whatever was laying around. Gradually, he added decorations, like horseshoes and a model boat.

For Blackwood, this was the model of what it was to care for this place and our relationship to it—nothing goes to waste; you use everything you have at hand, and you don’t just tend but you do what you can to keep it beautiful. At The Rooms in St John’s, the provincial art gallery, this is the Blackwood you can buy a poster-print of. Even its simple wooden latch feels loving and iconic. The Blackwood family eventually purchased the door, and the shed that came with it; his brother Edgar needed somewhere to store his lobster gear. Eventually, Blackwood donated Ephraim’s actual door to the Rooms, where it remains on show.

It’s not entirely clear at first why his 2010 etching of the door is titled Autobiography, until you look closer. In micro detail, Blackwood has inscribed on the door the names of those who made his life what it was—friends, family, teachers, and artists. The circle Ephraim had roughly drawn at its centre glows with a fiery warmth. You build a life with what’s around you, the leftovers, the mismatches, the things to hand.

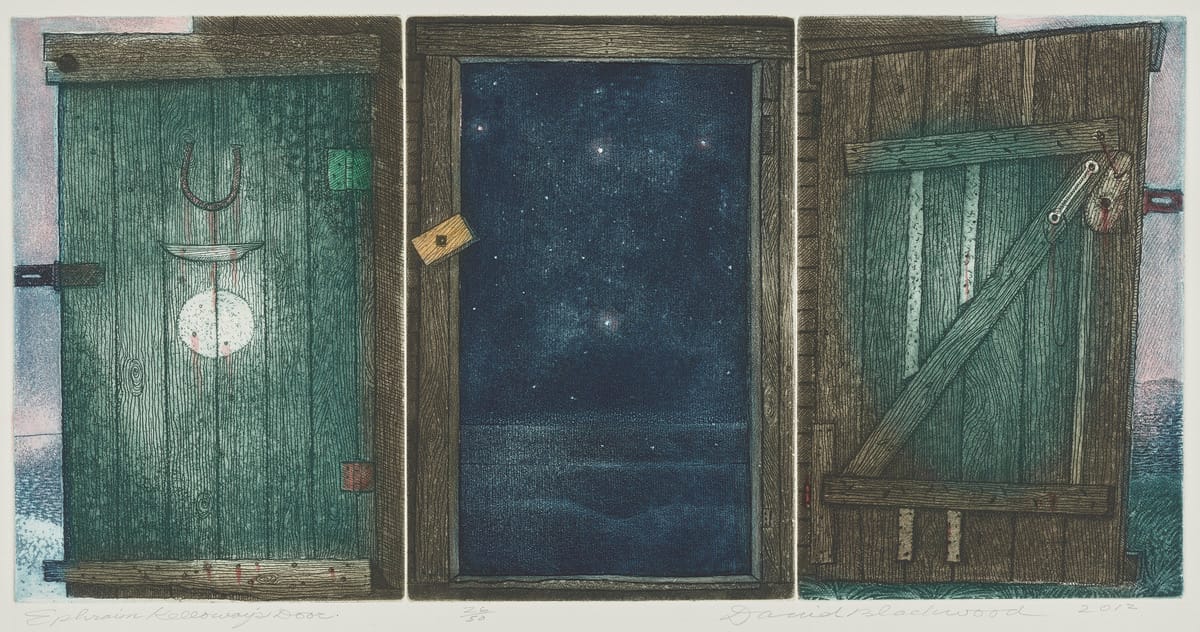

In the 2012 triptych titled simply Ephraim Kelloway’s Door, Blackwood finally does something he’s never done before—he opens the door. At last, we see what the shed looks out on—in the moment, a rare, cloudless Newfoundland night, so dark that the land itself almost slips into the endlessness of the universe beyond. There could be anything out there. And everything.

David Blackwood: Myth & Legend runs at the Art Gallery of Ontario until July 26, 2026.