A City Ready for Rupture: First-Wave Punk in Toronto

How Toronto’s early punk scene erupted into life, shaped by art school, DIY spaces, and a city steeped in constraint, boredom, and borrowed influence—told by people who were there.

Punk arrived in Toronto almost in real time. While the scene in New York was cohering around CBGB in 1974–75, with London quick to follow, by late 1976 Toronto was already brimming with bands and makeshift venues operating with a shared sense of unruly purpose. While The Ramones’ September 1976 show at the New Yorker Theatre on Yonge St., booked by Gary Topp, is often credited as being the spark, the tinder was already there: within weeks musicians were forming bands and a small but passionate audience showed itself ready for something more invigorating and challenging than bloated arena rock.

By early 1977, Toronto punk wasn’t merely reacting to New York—it had its own local figures, infrastructure, and internal momentum, unfolding with a speed that suggests how primed the city was for a rupture. In historical terms, Toronto’s scene wasn’t late to punk; it arrived almost alongside it, close enough to feel like a parallel emergence rather than just an echo.

Clustered around venues like the Horseshoe Tavern and Crash ’n’ Burn, bands such as The Viletones, Teenage Head, and The Diodes turned punk into a local argument about decorum, creativity, class, and the limits of Canadian politeness—embracing the confrontational and obnoxious when necessary. The city could pride itself on a self-sustaining network of bands, record shops, zines, and promoters that rivalled in its intensity scenes in other punk hotbeds like Cleveland, Boston, and Southern California. Even if Toronto’s first-wave scene never quite produced that single breakthrough act (arguably, Teenage Head came the closest) its significance lies more so in how quickly it localized punk in sound, attitude, and infrastructure: breaking from the template of hard-fast-loud to incorporate a diversity of sounds and styles, while helping to carve out a space for DIY culture and alternative media in a city better known then for restraint than rebellion.

Taking its cue from the punk-inspired aesthetic of Tracey Snelling’s recent exhibition Intergalactic Planetary, in early December Koffler Arts hosted a panel discussion on the origins and legacy of Toronto’s early punk scene. Participating in the conversation were Liz Worth, novelist, poet, and author of Treat Me Like Dirt: An Oral History of Punk in Toronto and Beyond; legendary music promoter Gary Topp, who booked The Ramones for their catalytic first Toronto gig; and visual artist Ian MacKay, bassist with The Diodes, whose basement rehearsal space became the short-lived Crash ’n’ Burn, considered Toronto’s first punk club.

The panel was moderated by curator David Liss. While growing up in Hamilton, Liss was childhood friends with members of Teenage Head and attended many of the concerts that Topp promoted back in the day. In the early 80s, he started presenting his own shows at a Hamilton dive bar.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

DAVID LISS: So punk—it’s a four letter word. But within that word there’s a pretty rich subculture. It certainly was in Toronto, which was one of the first cities to have a punk rock scene. Just to get things going, let’s clarify things. Liz, how would you define punk?

LIZ WORTH: It depends on the era you’re talking about. I always gravitated to first-wave punk. Even though I was born after the fact [in 1982] when I was a teenager discovering music, it was bands like The Clash, The Ramones, and The Damned that were really important to me. And then through researching that history, I found that punk was a lot more than I think people of my generation were putting together.

It’s really easy to just look at current bands and think that a scene begins and ends with the present moment. But when I started looking back into punk history, punk became so much more than music and fashion. Of course, those are two things that are really important to it, but for me, punk has always been about freedom of expression and creativity and innovation in all genres, all mediums. It’s also poetry, it’s photography, it’s art, it’s performance, it’s many layers of things. I’ve always looked at it as a place for people to become anything that they want to be.

DAVID: I’ve heard some people refer to 1976 as the year zero of Toronto punk. When Teenage Head started out in 1975, in their bass player’s driveway, I don’t think they were thinking about punk or even necessarily aware of it. But when the Diodes came along, Ian, did you consciously want to start a punk band?

IAN MACKAY: Just backing up a little bit from there, I think the Ontario College of Art experience plays a pretty big factor in the development of a lot of bands that came out of that period. It really kind of started with what some people call the “Thornhill sound” and this band called Oh Those Pants, which was a 12-piece band that played the Beaux Arts Ball at OCA. They had two lead singers, two drummers, five guitars, they were like Broken Social Scene back then. It was hilarious because they adopted all kinds of costumes, they played the role of the Rock Star deliberately as a kind of parody. Simultaneous with that, there was another band playing The Beverly Tavern on Queen called The Dishes. Many of you probably heard of The Dishes associated with the artist collective General Idea.

In that early moment of ’75, ’76, the music scene around OCA was really nascent and not well defined, it was kind of a glam, queer culture. It was amorphous. For many of us, the concert that Gary put on that brought The Ramones to the New Yorker almost became like a gold vein that everybody just grabbed onto, because here were four guys playing very basic material—it appeared as though anybody could just decide, “I’m going to start a band.” And so, we combine what was going on at OCA with the sound lab there, the video, the electronics, then added in this sudden “do-it-yourself", loud, aggressive, somewhat easy to play music—it felt very empowering for a lot of people.

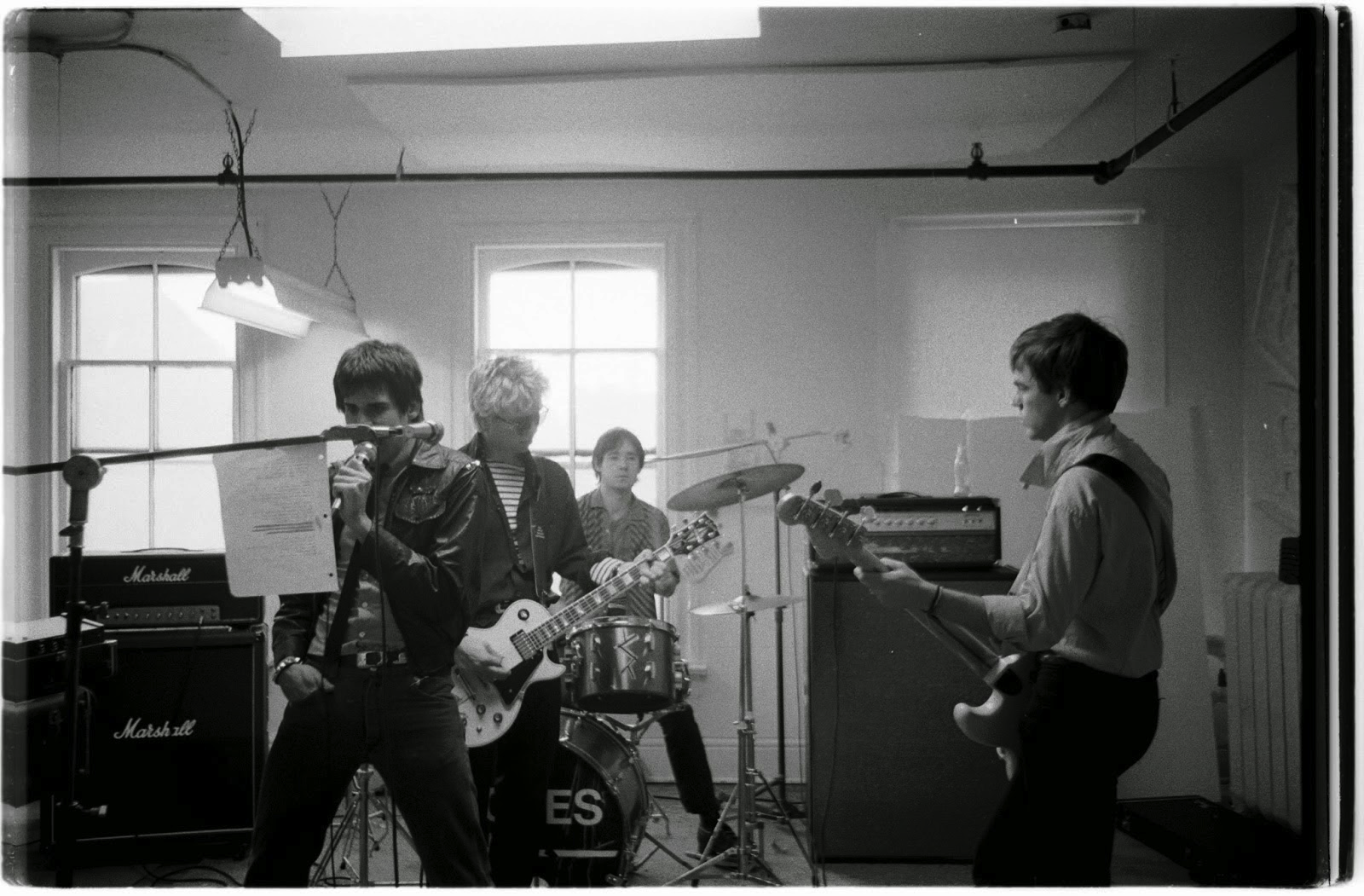

Out of that Ramones concert, a lot of people picked up guitars. We all had them as kids, but a lot of people picked up guitars or drums or whatever, and then eventually started playing regularly in little rehearsal studios. We essentially had the keys to the OCA experimental arts area, so we used to practice there in the evening. The first concert was a band called The Eels, which opened for Oh Those Pants at OCA. That morphed into the Diodes just shortly thereafter. I joined the band at that point.

The groundswell that was going on in and around the Ontario College of Art was an enabler. Yet this event at the New Yorker became a major catalyst for a lot of people. That’s my historical understanding.

DAVID: Were you guys consciously aware of punk rock?

IAN: We were aware of what was going on in New York, and the UK was just starting to develop, it came a little later. But it was very broadly defined, right? It wasn’t exactly only guys in leather jackets. You contrast that with Talking Heads, with Blondie, it was a very wide range of musical tastes and influences. In Toronto, you had The Poles, you had The Viletones—two very different bands on the musical spectrum. I guess the Diodes chose this middle path. We wanted the aggressive, loud music, but we also wanted to be clever, ironic, whatever. That kind of thing.

DAVID: That’s a good segue to the show Gary put on at The New Yorker. Gary, you were putting on music shows and film screenings from the early 70s, if not late 60s onward. When you booked a band like Ramones, did you feel like you’re bringing the punk rock thing to Toronto, or was it “They’re just a band”? Was the term even being used at that point, in 1976?

GARY: When you look at all the bands that were in Toronto at the time from ’76 to 1980, very few of them were punk. The three scenes were New York, London, and Toronto. Unfortunately in Toronto the media didn’t care about any of this stuff for years. Not until when The Edge closed in 1981, around the time of the first Police Picnic, did the media start thinking about it. There’s a lot of people here tonight I know who have been to a lot of shows. So I made this list—some of you will know all the bands. Very few were what you’d call punk.

There were the B Girls, the Cads, the Dents, the Diodes, the Dials—the only band on this sheet I never booked was the Dials, I just couldn’t relate to the singer—the Dishes, the Existers, the Government, the Mods, the Poles, the Scenics, the Swollen Members, the Ugly, the Viletones, Zro4, Tyranna, True Confessions, Everglades, Raving Mojos, Nash the Slash, the Fits, Screamin Sam, Androids, Robbie Rocks, Rough Trade, the Wads, Drastic Measures, the Secrets, Rent Boys, TBA, Hi-Fis, who became Blue Rodeo, the Bobcats, Stark Naked and the Fleshtones, Cardboard Brains, the Curse, Arson, Crash Kills Five, L’ Etranger, Blue Peter, Martha and the Muffins, Johnny and the G Rays, the Numbers, Tools, the Points, Bibi Gabor, the Fictions, the Sharks, the Basics, Popular Spies, the Biffs, Steve Blimke and the Reason, The Cubes, Hydraulic Chaos, Space Phlegm, Dead Bunnies, the Velours, Battered Wives, Daily Planet, the Time Twins, Spoons, Deserters, Rheostatics, Toby Swan and the Sidewinders. Plus reggae was becoming popular: Earth, Roots and Water, Ishan Band, Truth and Right, Chalawa.

These were bands that we booked between The Horseshoe and The Edge from ’78 to ’80. These were all local bands. Very few of them are what you think of as punk, like the Viletones or the Ugly. A lot of them were performance artists, great performance artists. They were artistic. I had a movie theater called The Original 99 Cent Roxy which ran from ’72 to late ’75. A lot of these kids—I call them kids because they were, Gary Cormier and I were older—came to The Roxy. Stephen Leckie from The Viletones used to come to The Roxy to see a classic French movie from the 40s called Children of Paradise. We also tried to screen Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls at The Roxy—it was packed, but just as we were about to turn the lights down the morality squad came in and confiscated the movie, which I had rented from the MoMA.

In that period, the music was changing, in New York especially, and we were very connected to New York, we were also very connected to England. Everybody was reading about all this stuff. The first time I heard the word punk was actually in connection to Suicide, well before The Ramones.

I’m glad to have been part of that generation, and right in the middle of this scene. When we saw somebody we liked, we booked them and nurtured them and tried to get press for them, help build them up. I mean, that’s what parents are for.

IAN: Sorry, I just wanted to interject something, if I may. I think there was a real emphasis in ’75, ’76, on this idea that you could span media as an individual creator. You could run across fashion, you could publish your own zine, you could pick up a guitar, you could start a restaurant. We couldn’t make our own records yet, we didn’t have the technology, but there was something about that particular period and the cross-fertilization that was going on among so many people that led to this explosion of creative output. The club Crash ’n’ Burn, which lived three months or less, came directly out of that.

But of course, that was part of the whole ethos, right? It was dress, it was publishing, it was making music, it was making art. We didn’t have the internet yet, so we had to make do.

The Last Pogo, a documentary by Colin Brunton, captures what many consider the last of Toronto's first-wave punk shows, on December 1, 1977, at The Horseshoe Tavern. The show ended in a mini-riot.

DAVID: Liz, do you feel that there’s such a thing as a punk ethos? If so, can you talk about it through the people you’ve spoken to that were there?

LIZ: I think a lot of these things happen in hindsight. A lot of the people who I interviewed for Treat Me Like Dirt talked about that. That there wasn’t this sense of it being a scene or a movement yet, that only came with looking back. I think that is probably true for every decade. I think what punk has done is that it started something that began as counterculture. It began as underground, but then it actually took hold in the mainstream in a lot of ways that we’ve stopped noticing.

So when you’re talking about an explosion in media, for example, the peak of magazine publishing was in the 90s. Now we’re in this digital period, and yes, it feels weird, but there are now a lot of younger people under 30 who are creating at the same levels that people were in ’77. And things are happening again where there is more crossover at shows as well, where there’s less categorization. A punk show can mean many different sounds and many styles. These things are still happening. But punk has actually become so ingrained in so many aspects of our culture, it’s almost like it infiltrated fashion and sound and mindset. So people now are still taking reference from what happened within that first wave and they keep replicating it.

Again, we see it in so many ways. Zine culture is a big part of punk, even though it didn’t necessarily start there, but zines are still happening. The way people dressed in the 70s and 80s through punk fashion is stuff that you can now buy at H&M. These things are everywhere. So I don’t know if it’s so much about punk ethos, I think it’s more that punk opened something up for people and showed them that they could create in a lot of different ways. They could also take a different path in life. Because there are also a lot of people from the punk scene, like Ian, who came out of art school. At the time it wasn’t popular to go to art school. Now art schools have far more applicants than they can handle. But throughout the 70s and 80s, nobody wanted to go to art school.

DAVID: I went to art school.

LIZ: I’m just saying it wasn’t seen as a viable career.

DAVID: That’s what makes it punk.

LIZ: It’s music, it’s culture, it’s punk that started to change that because people started to take influence from what they were seeing that first wave doing. When we talk about ethos, it’s hard to define because it’s actually everywhere. And sometimes I think people are taking reference or inspiration from it without even noticing.

DAVID: Then punk continued to evolve. Some people think it was already dead and over by 1980 or even sooner. And, of course, some people think punk is not dead. Maybe as soon as something gets labeled, as humans like to do, we pin it down and study it, it becomes static—and stasis is death. But in music you then had a second wave of punk, like in Southern California, and in Toronto you had Bunchofuckingoofs, certainly punk continued. There are still hardcore punks out there today that are rocking that original spirit.

Not Dead Yet is a documentary about the Toronto punk/hardcore scene circa 1983.

IAN: I think Gary’s original premise of this very wide variety of musical output is probably more accurate for Toronto. There really was incredible diversity. Eventually many bands decided to pick up styles and references from earlier music eras, for example The Mods or even Blue Rodeo. Country music went through a major kind of retrofit or resurgence on Queen Street West in the early 80s—musicians were self-consciously picking up older influences, as opposed to what I think people were doing in the 60s and early 70s, which was more a continuation or an evolution of music up till that point, which is how we got progressive rock. Much of what this DIY stuff did is it reached back into popular musical history and took out what they felt suited them for their particular genre or style of music they wanted to pursue.

DAVID: Maybe slightly off topic, I wanted just to acknowledge Gary for when he brought William S. Burroughs to The Edge. What a show that was. Well, it was William Burroughs reading, but there seemed to be a lot of that same punk or alternative crowd that were going to see the Head or the Rebels at The Edge the previous night or week.

GARY: The crowd, they came to the Roxy and watched Jean-Luc Godard and Roger Corman movies on the same night. They weren’t punks like Sal Mineo, they were a very cultured group of people. Hence, the music they produced reflected that. Also, the way they promoted themselves. Nobody promotes themselves now like they did, you don’t find that now, now it’s all Live Nation or whatever. These kids were all on their own. There were few clubs where they could play—it was just a fabulous, interesting bunch of people.

DAVID: When we were putting on shows in Hamilton, Hamilton at that time had more of a biker culture than punks. And the bikers weren’t actually that keen when the punks from Toronto started showing up. There was even a bit of tension in the air with that clash of cultures, which could be explosive. When Liz interviewed me for a book a number of years ago, she asked how I wanted to be classified. I said I was just a fan of the music.

But I also feel like the audience back then was part of it in a way, like there was less of a delineation between performer and audience. Of course, a lot of the audience were also in bands, plus you’re playing in small dive bars and whatnot, so everybody’s all in the room at once. With Teenage Head, they were the same as everybody else, just they had their instruments waiting on stage. So not only was there crossover between genres, but crossover between audience and performer also, what with all the fashion shows, poetry readings, those kinds of things. This was maybe before things got more siloed. Is that fair to say, Liz?

LIZ: I do agree that things became siloed. As you said, people like to put labels on everything. Unfortunately, that’s this natural inclination people have, sometimes you really want the either/or option. Everything becomes a binary of this or that.

When we’re talking about the first wave, it also has something to do with the proximity to Andy Warhol. Because Andy Warhol was also doing all of these things. He was doing art, he was making films, he was involved in performance, he was involved with the Velvet Underground. He had this hub where all of these different art practices were centering around him, and he was pushing out so many ideas. But he didn’t just represent one thing, he did many things, and he became known for all those things.

To have somebody like that with such a level of influence at a time when mainstream media had such a trickle-down culture in a way that it doesn’t anymore, because so much of our communications have become flattened, and we are spending so much time paying attention to different sources of information. But at that time, if mainstream media was talking about someone like Andy Warhol, then a lot of people would have awareness about someone like Andy Warhol. And that would also be planting seeds around, like what could I do?

Could I have a band as well as be an artist, as well as be putting on weird performance art? Now we’re many years out from Andy Warhol and punk is coming up to its 50th anniversary. The more that time passes, the more we lose that type of context and collective memory of having that kind of proximity.