Filling in the Gaps of Family Memory

From his talk at the Koffler Gallery, visual artist Rafael Goldchain on his photographic series I Am My Family and how its approach to simulation as a means of commemoration represents a “double gesture towards the past”—an attempt to both recuperate and interrogate history.

As part of programming around the exhibition, “The Synagogue at Babyn Yar: Turning the Nightmare of Evil into a Shared Dream of Good”, Koffler Arts has invited speakers from various artistic and academic backgrounds to present talks based on their insights and responses to the exhibition. In October, the Koffler Gallery hosted the celebrated Toronto-based visual artist Rafael Goldchain, who spoke about the resonances between the Babyn Yar synagogue and how his own work functions as a kind of commemorative project, characterized by his interest in family history and genealogy.

The 70-year-old Goldchain was born in Santiago, Chile to Polish-Jewish parents. Much of his early work employed portraiture and personal documentary to explore the theme of exile in a Latin American context, rooted in his experiences of Chile, Mexico, and Central America. By the time Goldchain was living in Toronto, in the 1990s, his practice shifted toward the studio, where he began experimenting with a mode of performative self-portraiture that would result in his landmark series I Am My Family. His photographs are included in the collections of major museums, including the National Gallery of Canada, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Museum of Modern Art, the Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y Las Artes (México), and the Biblioteca Nacional de Chile.

This transcript of Goldchain’s talk has been edited for clarity and length.

*

This presentation is different from ones that I’ve given in the past, it has a different objective. Those presentations were mainly a way of focusing on my diverse bodies of work and tying them together. How did these diverse things stick together over the arc of an artist’s career? I’ve been told that my work is eclectic. I’ve been told that sometimes it’s hard to figure out how I move from one set of photographs to the next, that they don’t seem to be connected. And so my efforts in the past have been aimed in that direction, with some degree of success.

Today, that’s not what I'm doing. Today I want to focus on how my work, I Am My Family, can be thought in terms relating to the current exhibition here at the Koffler, “The Synagogue at Babyn Yar: Turning the Nightmare of Evil into a Shared Dream of Good.”

As its architect Manuel Herz has stated, the new synagogue’s major theme is commemoration, and the reestablishment of a living Jewish presence on this site of Babyn Yar. We can see how the depth and intensity of the experience of the synagogue and the site is rendered immersive by the large-scale photographs on the walls. How the synagogue resembles a pop-up book, in the way that a pop-up book is sort of a gateway to the imaginary—it creates an imaginary. But that imaginary is really based on the details. While the overall architecture is exquisite, it’s all the little details that make it come alive for me, like the wall decorations. So the viewer is immersed in a simulation of a historical synagogue while at the same time being aware of its status as a simulation. You allow yourself to be taken into the space of the synagogue and imagine it as a historical Ukrainian wooden synagogue as they would have existed in the past.

Although some people are using it today for prayer services, its primary contemporary function is as a commemorative site—as a place where people go to remember, experience the depth of history, perhaps to mourn and grieve.

Simulations can play a role in what the anthropologist Jonathan Boyarin calls a double gesture towards the past. In thinking about Walter Benjamin’s ideas about history, Boyarin emphasizes both “the yawning gap between us and the past, and the past’s proximity to us, suggesting the need for a double gesture towards our past. We need constantly to be interrogating and recuperating the past without pretending, for long, that we can recoup its plenitude.”

So the past is near, but we can’t reach it. And we certainly can’t recoup the fullness of it. And that’s kind of what a simulation is. We are tempted or encouraged to immerse ourselves in a sense of pastness.

My relationship to my familial and cultural past is not much different from that of a lot of Jewish people, and a lot of people who have experienced the sometimes very violent and fracturing events of the 20th century. While I’m not the son or grandson of Holocaust survivors—and I'm aware that I'm very lucky for that—many members of my family in Europe did not survive World War II. Because of that shared history, many of us feel like we live on branches of a tree that was cut off from its roots, by over a century of pogroms, massacres, and ultimately, the Shoah. That’s my sense of a relationship to my history.

When I began work on I Am My Family, in the late 1990s, I had just entered the MFA program at York University as a mature student, an impressionable young man of 46. I was very influenced by Cindy Sherman, who at the time was having a huge retrospective exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. I had already made one successful experiment involving the memory of a relative, and done many photographs of myself as various kinds of characters, and I wanted to keep working with self-portraits. Though I had been photographing other people for a long time, it felt like the most honest way to tell a story was to actually photograph myself. (Besides, as a model I’m very accessible and very cheap.) So I did a portrait of myself as a grandfather that I remembered, that I had a living memory of, because he lived with my family for a couple of decades. Then I did a whole lot of other self-portraits.

When my MFA review committee came to my studio, sat down, looked at my work, all of them pointed to that self-portrait of me as my grandfather and they said, “That’s the one, that’s not Cindy Sherman. That’s the one that is genuine, it has a conceptual and emotional depth that is linked to you.”

I thought, “Okay, I have my marching orders, right? This is what I'm going to do.” Instead of doing self-portraits, à la Sherman, I’m going to, in a way, try to populate my family album with simulations of myself. I developed a list of family members I thought I knew something about, recording my memories of them, knowing my memory would be full of holes and sadly brief. Many on the list I’d only known as a child. Others I had been told about only briefly.

Then I reached out to my parents and other relatives, asking for photographs and family albums that I could use as reference. And I asked for stories, with many emails going back and forth, a lot of which ended up in a scrapbook. Then, about three years into this project, I was visiting my mother in Mexico City and she says, “Oh, I have something for you.” She knew I’d been working on this project for quite some time, and she comes back with an album that I had never seen in my life. It would have been really, really helpful if I had been able to see these pictures three years before!

I grew up with a sense of having a really small family, going back to that truncated tree. There were my parents, my brother and I, my aunt and uncle and cousins, and grandparents. And that was it. No great uncles or more cousins, etcetera. But by doing this project, it felt like my family tree was suddenly becoming a bit of a forest, as I became aware of a much larger group of people that had lived at one point or another, and with whom I shared a sense of belonging. Even if I didn’t know very much about them. In fact, there’s a lot of them that I didn’t know anything about because I created them. I will get there shortly.

Another factor that came into play, is that around when I started doing this project I was the age my grandparents were when I was born. I thought a lot about what life was like for them. They had recently arrived in Latin America with no Spanish language or culture, from an Eastern European culture. What were their challenges? How did they sort themselves out? I asked a lot of questions of my father and mother. My mother had a bit of dementia by then, so her memories weren’t clear, but my father could recollect things. I was coming into possession of a history that I had not heard before.

And one more factor that came into play—when this project first started, around 1998-99, it was the early days of online genealogy. Now it’s a craze, right? Some of you out there are probably on Ancestry.com or Geni, or something like that, lurking your family centuries back. For obvious reasons, there’s long been a keen interest in Jewish genealogy, so in my early research I find there is a whole host of people transcribing Jewish genealogical records from Russia, Ukraine, and Poland online for the rest of us to research.

At the beginning the information is quite scant. It’s just numbers and dates recording births, marriages, deaths, and not much else. Over the years, it’s become more thickly populated with information. If you have the names of the parents, and then the names of their parents, and the years, and so on, you’re able to reconstruct the line from which you come. The archives of Yad Vashem are also full of information, including the post-war paperwork survivors filled out that basically accounted for those who were lost, accounted for those who were killed. Bearing witness to what happened during the Shoah.

Beyond trying to find links between my known family, and the names I was finding in genealogical research, I began to see how the names and the absence of images could move my project beyond my known family to a more imaginary one. Here, I come back again to the pop-up books, where you open it up and you're creating an imaginary world.

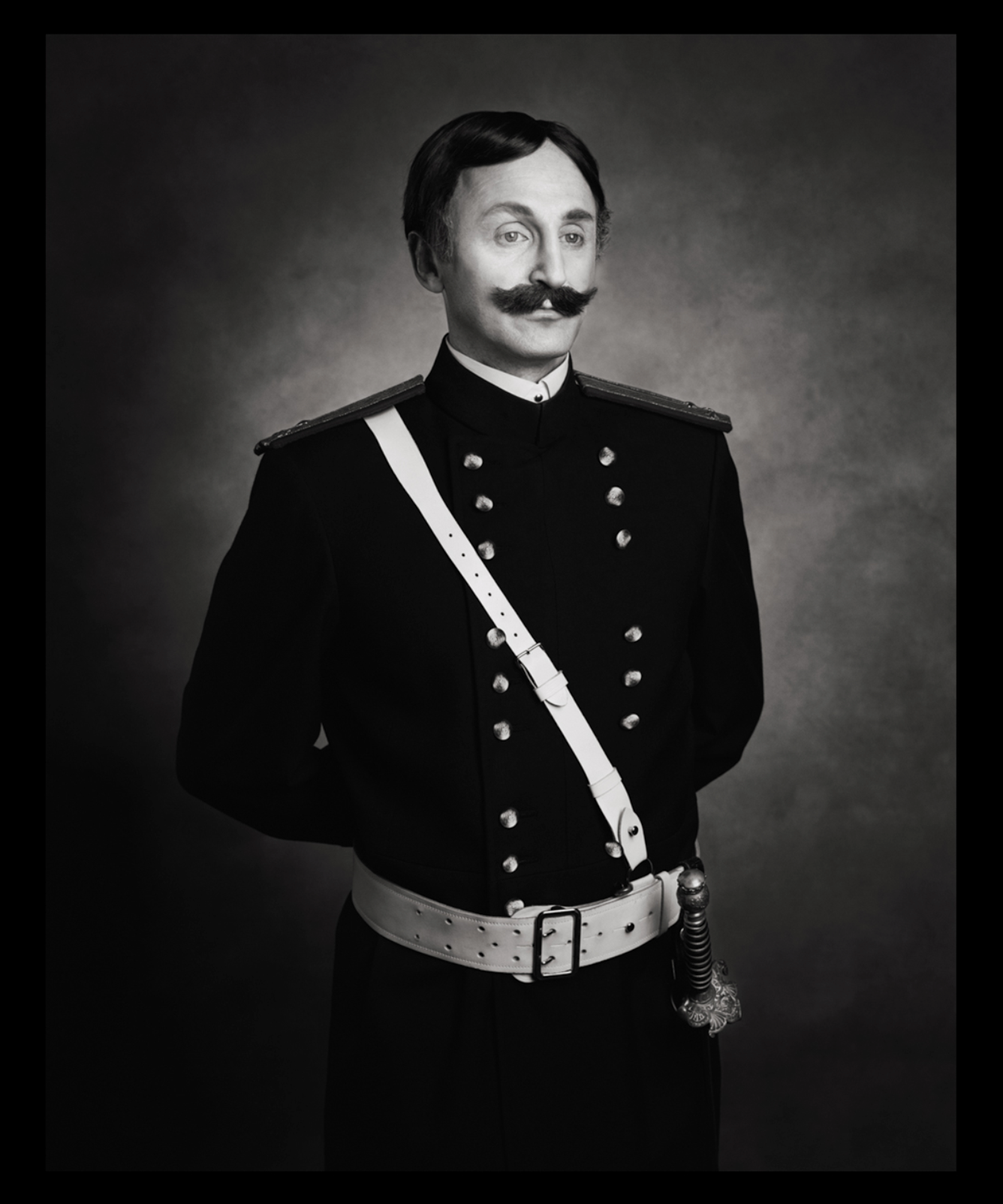

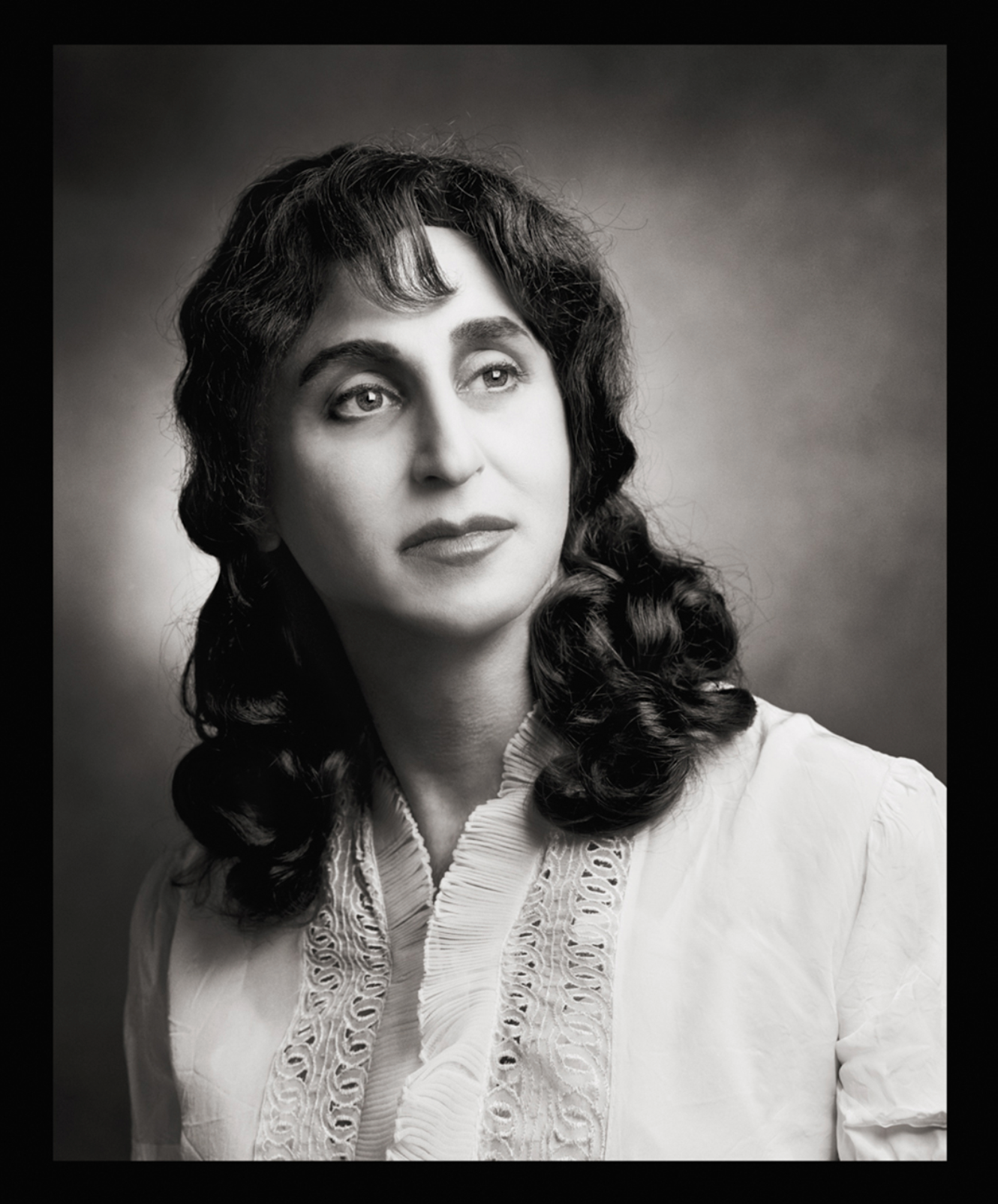

Left: Self-Portrait as Edmund Precelman (Officer) b. Poland, 1890s d. Poland, early 1940s. Right: Self Portrait as Malka Ryten b. Lublin, Poland, 1884 d. Tel-Aviv, Israel, 1974. From Rafael Goldchain's series I Am My Family.

I realized that my family was just one set of cells or units in a much larger Jewish world, and that I could use this project to conflate a much larger pre-war Jewish world, rather than stay within my family. So I started inventing characters, looking for a broader range of personae, occupations, and with not a small amount of tenderness and satire. Initially, with the first set of photographs I took care not to offend anybody. I was afraid that I was treading on hallowed ground, I did not want people to see these pictures as cartoons. But eventually, I kind shed those misgivings and decided that I could have a little fun, play a little, create a family that had all kinds of lovable characters, some of whom you could even laugh at.

Here is this idea of the simulation serving as a site of commemoration in my work. I saw my images precisely as simulations that could elicit the experience of remembrance, while at the same time being experienced as performances in the present. In these photographs there are two time frames. There’s the present moment, during which the model, me, is performing in front of a photographer, and then there’s the moment at which the person from the past being brought to life, so to speak, was posing for a photographer.

Over the course of my research I ended up with tons of names. I had no pictures for these names, but some of these names were evocative. So I started attaching these names to images that I made to create personae that really were more invented than anything else. Why? It was fun. It was meaningful. It was a way of alluding to a much larger family and a much larger world.

I read an author who said, “The gaps in memory are the motor of the imagination. The holes in history are the places where you can create.” And so, I gave myself license to create within those holes. I set out to create characters—half-real, half-invented, or, in many cases, completely invented. The impossible task of filling all the holes in memory led to the later realization that it was not my family I was reinventing so much as a larger collective family. Therefore, I needed to have representatives from various sectors of society—young and old, male and female, poor and wealthy. In each image I inserted myself into my own history. I imaginatively projected myself into my ancestors’ lives as if fundamental aspects of their lives were key pieces in my identity.

For example, there is a photograph of myself reenacting my paternal grandfather, as photographed by my father before I was born. A bit of folding in history. In the original photograph he wasn’t smiling. But there was no impulse on my part to dress up and slavishly recreate these photographs. I wanted to depart from those photographs imaginatively and create new personae.

Marianne Hirsch theorizes something she calls postmemory. Postmemory is a powerful form of memory because its connection to its source is mediated. Not through recollection, but through imaginative reinvestment in creation. Your parents tell you stories, and down the line in your life, you believe, in a way, that you lived the experience. Those stories overhang your life, they become determinants in your experience.

The difference between real memory, or living memory, and postmemory, according to Hirsch, is that post memory does not hide its exploration, its probing of relations with the unknown past. I couldn’t possibly recreate people totally, detail by detail; it’s obvious to anyone looking at these pictures that they are a construction. They are a performance. They are imperfect. And yet, they gesture towards the past with a certain longing, a certain satire, to some sort of relationship with that ancestor.

As for commemoration and memory in relation to the synagogue at Babyn Yar, these self-portraits are motivated by the impulse to resist oblivion, to resist forgetting—our natural forgetting, but also the forgetting that happens as a result of a catastrophe, when peoples’ lives are obliterated. To affirm a sense of the historical continuity that I did not experience as a child or as a grown-up, and of obstinate survival in the face of family fragmentation, extinction, displacement, and loss.