How to Survive in a Cold Climate

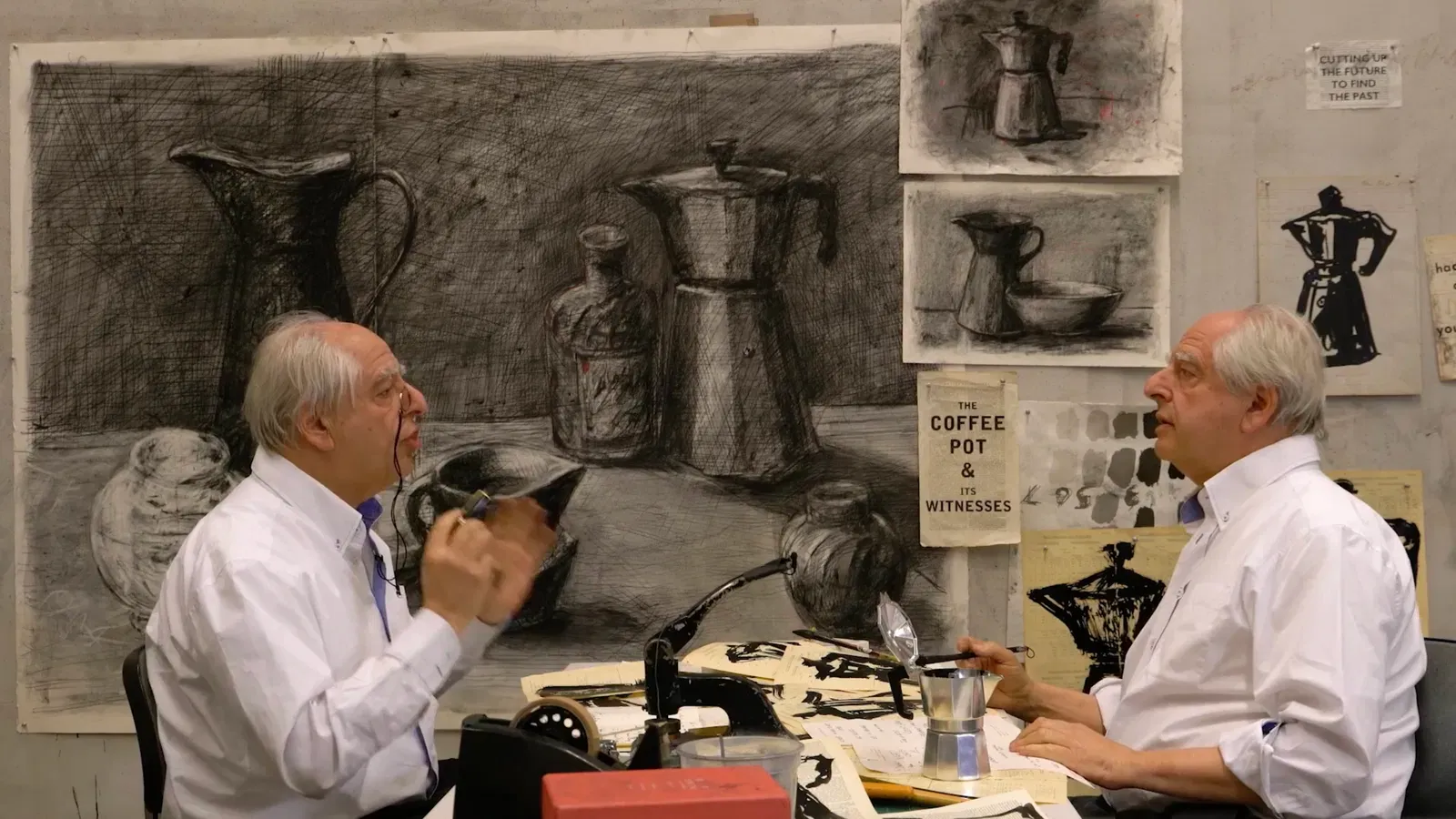

In The Audacity of Relevance, Alex Sarian argues that struggling non-profit arts organizations need to adopt a more audience-based model.

Sometime in 2023, when most of the last pandemic-era restrictions were finally lifted, we were introduced to the idea “funflation”—that there would be a dramatic surge in consumer spending on live entertainment and other experiences. Sure enough, moviegoers flooded back to cinemas, drawn by blockbusters like Barbie and Oppenheimer, while artists like Taylor Swift and Beyoncé once again packed stadiums, this time at even more jaw-dropping ticket prices.

The benefits of funflation, however, proved largely elusive to many non-profit arts organizations across Canada—from theatre companies and performing arts venues, to galleries, and music and film festivals—who struggled to bring back audiences they had lost to the pandemic. “Organizations emerged from lockdowns to surging costs, dwindling audiences, hesitant philanthropists, distracted corporate sponsors and mostly stagnant government funding,” reported The Globe and Mail. Was it a matter of economic pressure, shifting tastes, or something deeper?

Alex Sarian, CEO of Calgary’s Werklund Centre and author of The Audacity of Relevance: Critical Conversations on the Future of Arts and Culture, doesn’t mince words when it comes to answering that question. For Sarian, the sector’s ongoing struggles aren’t only or even primarily about money or marketing or the after-effects of the pandemic—they’re about purpose. “It goes back to the organization’s value proposition,” he says, “always asking yourselves ‘Why are we doing this?’” For those organizations who fail at connecting with the audiences they pledge to serve, Sarian adds, “You’re probably going to be out of the business in five years.”

While some have criticized Sarian for pushing non-profit arts organizations more toward the private sector, he points out that “[government] funds are going to get smaller whether we want them to or not,” and that in many cases issues of attendance and revenues preceded the pandemic, underscoring a persistent reluctance by arts organizations to interrogate their value proposition in a changing world.

Sarian joined the Werklund Centre, formerly known as Arts Commons, in May 2020, stepping into the President & CEO role at one of the youngest ages ever for such a position at a major North American performing arts centre. Under his direction, the institution is undergoing the Arts Commons Transformation (ACT)—a landmark cultural infrastructure initiative with a price tag of $660 million, making it one of the largest projects of its kind in Canadian history.

Before moving to Calgary, Sarian spent nearly two decades in New York City, holding senior roles at Lincoln Center—overseeing education, family programming, consulting, and global initiatives—and prior to that, as director of education at the off-Broadway MCC Theater.

Published in late 2024, The Audacity of Relevance is Sarian’s call to reimagine the role of arts institutions by centering community, civic dialogue, and cultural relevance over legacy and gatekeeping. In it, he challenges arts leaders to redefine their ideas of success—not by what they produce, but by how meaningfully they engage the people they claim to serve.

In this interview with Arcade, Sarian speaks about what it means to lead a cultural institution in an age of fractured attention and radically democratized access to content.

Why do you think, when so many other sectors benefited from that post-pandemic “funflation” phase, that the non-profit arts sector struggled?

Part of it was institutional hubris, which is not new by the way, this had been around for decades. You look at trends in attendance, ticket revenues, subscriptions, they were already heading in this direction. I also think it’s just being unaware, not prioritizing the right thing, not having the right values lined up. And I use the word value intentionally, like at the core of it, who are we doing this work for?

I find it so interesting how we as a sector were very quick to blame the pandemic. We’ve always found these scapegoats, right? We’ve always found these reasons as to why these things are happening. Last year there was this article by Josh O’Kane in The Globe and Mail on the state of the arts sector in Canada, and he listed all the reasons why the non-profit art sector is struggling—inflation, the costs of doing business, the evolution of philanthropy. But nowhere on that list did he articulate our own inability to navigate the situation, which I find to be the most egregious thing of all. That to me was just a reinforcement of how quick we are to blame others as opposed to saying, okay, “We’re either the leaders in this field or we’re not, how are we going to behave differently?”

An acquaintance of mine was telling me how he spent $6,000 for him and his daughter to see Taylor Swift in Vancouver. That’s flights, tickets, meals. And yet, when his favourite Broadway musical, The Book of Mormon, came through Calgary it was only $200 a pop. I asked him, “ Why on earth would you spend $6,000 for a concert by an artist you know nothing about, and whose music you don't even like, he said, “My daughter is 11. I will never get this time with her again, and it's her very first concert going experience.”

Basically he gives me all these reasons that have nothing to do with the actual art at the core of it. So when I come back to my day job, where we seem to be overly focused and overly precious only about that experience in the concert hall or theatre, it forces me to think about all the surrounding reasons and values why somebody might want to come to Werklund Centre.

You argue that arts organizations need to move away from what you call a transactional model to a relational one. Could you explain what you mean by that?

The transactional model implies that I have something you need, or I have something you want. What I argue is that there’s no way for me to have something you want or need if I don’t get to know you. I talk a lot about how at Werklund Centre I don’t even like to call ourselves an arts organization, I call ourselves a cultural organization or a culture house because I view culture as being the intersection of the Venn diagram between arts and civics. To me, culture is understanding people, engaging with people, engaging in dialogue with communities; how people decide to celebrate cultural identity or how they define cultural identity is not up to the organization.

Once we understand how people choose to identify and celebrate culture, our job is then essentially to elevate and celebrate it on their terms and not ours. I don’t know how you would establish that in a transactional model and not in something that is deeply rooted in relationship building.

But this idea of consultation and civic dialogue is hardly a new one. Many organizations do it, or make a show of doing it. Though often it risks being another box you check off to justify your next grant proposal.

It’s not new, no, that’s what boggles the mind. And yet for some stupid reason it needs to be said.

How do you get that dialogue right then?

It goes back to the organization’s value proposition, always asking yourselves “Why are we doing this?” If you’re engaging in civic dialogue or community engagement, and the only reason you’re doing it is to check the box, meanwhile you’re going to continue programming the same stuff you’ve always been programming… Well, guess what? You’re probably going to be out of the business in five years.

If you are engaging in dialogue, truly to listen and learn, because you have adopted a position of institutional humility, and saying, “Not only do I need to be in service to you, but my success is dependent on you valuing what it is that we do for you,” that’s completely different, that’s a paradigm shift.

What I argue in the book is that we need to have these conversations, and we need to be asking these questions, not just for optical reasons, but because if we can get it right, there is an economic impact to relevance. There’s an entirely different business model that starts developing itself once we lean into relevance, not out of a sense of hubris because we need to check a certain box to get grant money, but because we understand that our job is to serve the communities that surround us, and if they’re not coming, then we are failing.

There’s a very well intentioned question, which our organizations tend to be asked all the time, and that’s, what is your impact on the city that surrounds you? So I get asked all the time, what’s the impact of Werklund Centre on Calgary? Or what was the impact of Lincoln Center on New York City? But the question I’m actually far more interested in is what is the impact of Calgary on Werklund Centre? Will Calgarians see themselves reflected in the decisions that we are making because of the influence they have over us?

That requires a shift in how cultural organizations have been designed. We can look at the history of arts organizations, which is not very long, and say that we have been designed usually as these, you know, tastemakers or arbiters of excellence. You would go to Lincoln Center regardless of what was actually on stage, because it was Lincoln Center. That’s changing, and I think it’s a really healthy direction that we’re heading in, but it requires programmers and leaders and curators to redefine how they do things.

When it comes to arts funding and the long-term sustainability of organizations, where does Canada sit relative to the US or Europe?

I think in Canada we have an opportunity to define a new business model that is a hybrid between the European model and the American model. Clearly the model of public funding in Europe is one that appeals to a lot of organizations in Canada, compared with the privatization of the arts in the US, which is more dependent on philanthropy. But it’s important to point out that even in Europe that model is struggling.

A while ago I read an article in The Guardian about Berlin and how the municipality is pulling ridiculous amounts of funding out of the cultural sector. I think Canada, and ironically Calgary, has the opportunity right now to develop this hybrid model where we are still dependent on government funds, but we are also going to hold ourselves accountable to private investment. I actually think that’s a healthy tension because then you can go to government and say, “Listen, for every dollar I’m getting from you, I’m out there generating two from the private sector. And that private sector investment is proof to you that what we are doing is resonating with citizens.”

You’ve been criticized by some for wanting to privatize the Canadian arts sector.

My response to that is, “Listen, government funds are disappearing. Those funds are going to get smaller whether we want them to or not. A, because government funding is going down, or B, because the non-profit sector continues to grow at a rate such that the resources required to support them aren’t, or C, a combination of both.”

In the U.S. it’s so heavily dependent on private sector money that all of your lobbying and advocacy isn’t for increased arts funding from the government, it’s more around policies and legislations that govern nonprofits, philanthropy, and giving tax deductions. In Europe all of your lobbying and advocacy is probably going to be around fighting for state funding to either stay flat or increase.

What about Canada?

In Canada it’s messy, because we actually have legislation and laws that incentivize the private sector, but we also have a government that wisely chooses to invest in arts and culture. So, ironically, we have the building blocks of a hybrid model, but the narrative isn’t really there. What ends up happening is we have a lot of private sector individuals that say, “Well, why should I give when you get money from the government, when my taxes pay for it?” We’ve never been able to crack the narrative around saying, “Yes, your taxes help pay for this, and we are so grateful to you and the government. But guess what? That funding only covers 30 percent of our operating expenses.” If some of that messiness is cleared up it makes us uniquely positioned to succeed in a way that straddles both these worlds.

I wonder how applicable some of these ideas are to smaller non-profit arts organizations, who might lack the institutional capacity.

I will argue that it’s the smaller organizations that tend to be nimbler, and small enough that they are based on relationships. There are examples of success—like the Laundromat Project, which I write about in the book—more likely to be found in smaller institutions that are hyper-local in their impact, hyper-local in their relationships, better at having their finger on the pulse. They don’t have the institutional size that can make it hard to pivot or be responsive to the community. So while those smaller institutions might struggle because of capacity issues, which has always been the case, I actually find that when it comes to value propositions, they tend to be far more relevant and far more responsive than larger ones.

When you talk about creating dialogue around programming choices you express it as holding artistic intention and audience perception in a healthy tension. But what does that look like in practice?

The trick question is what’s more important, the intention of the artist or the perception of the audience? And it is a trick question because, as we all know, the magic happens when you’re in a theatre or concert hall, and the energy coming from the stage is being matched by the audience. We know that magic when we feel it.

I know what that looks like on either end of the spectrum. You might have an amazing show on stage, what the artist thinks is God’s gift to theatre, but nobody in the audience cares. And that’s painful to me to watch. I also know the opposite end of that spectrum, when you are spoon feeding something to an audience because it’s exactly what they want, and there’s no element of surprise or delight or challenge.

The other thing I’m accused of is, “Oh, you care too much about what the audience thinks.” That I don’t care about what the artists have to say. You know, I’m the first one to always say, artistic excellence and creative excellence is a non-negotiable. But it doesn’t have to be one or the other. What I always ask my team is, “Are we putting creative excellence in service to something greater than itself?” Otherwise, we’re navel gazing.

When I talk about the opportunity to engage with others, what I find interesting is that good artists are already doing this. A true artist is already an arbiter of relevance—I truly believe that—and what I find fascinating is, okay, if an artist is an arbiter of relevance in their own work, and if an audience is also an arbiter of relevance by how they choose to spend their time and money, then we have built these institutions that are literally meant to connect these two parties and we have contributed to our own irrelevance.

The pandemic showed us that artists didn’t necessarily need an organization, they just started a Zoom and I could watch somebody perform from their living room. To me, that was the epitome of relevance. Somebody created something that was impactful and necessary, and audiences wanting and needing that.

For a hot second during the pandemic, I thought we were watching the dismantling of arts institutions. And I was okay with it because we were essentially bringing the artists and communities together in ways that we had always gatekept. I think we now have to find a new value proposition to say, okay, if I can, if I can watch someone perform live from their living room on Zoom, then why the heck do I need Werklund Centre? That is a valid question and one we need to get out ahead of.