More a Book than an Ocean of Concrete: How to Tell the Story of the Babyn Yar Synagogue

“The Synagogue at Babyn Yar: Turning the Nightmare of Evil into a Shared Dream of Good” is as much an exhibition about how to memorialize a traumatic, genocidal event as it is about the synagogue itself. To mark the end of its run at Koffler, we look back at how this unique show came together.

Few exhibitions are as complex or as logistically daunting to stage as the Koffler’s current show, The Synagogue at Babyn Yar: Turning the Nightmare of Evil into a shared Dream of Good. And rarely are they made to come together so quickly. “Typically, for a show like this, you’d have a couple of years preparation time,” says Anthony Sargent, Koffler Art’s former Interim Director. “Here we had 14 weeks.” Despite the obvious challenges, Sargent points to the upside. “One of the good things with these incredibly compressed timescales is there is no time to mess about.”

To mark the exhibition’s closing in January, we present a behind-the-scenes look at the making of this remarkable show, as told by four of the people responsible for its creation: architectural historian Robert Jan van Pelt, who curated the Koffler exhibition and served as an advisor to the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre that commissioned the synagogue; the synagogue’s architect, Manuel Herz; Sargent, the Koffler’s Interim Director at time; and architect Douglas Birkenshaw, who installed and helped design the show.

–

ROBERT JAN VAN PELT: When the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center was created in 2016, the historiography of the site, and the massacre that occurred there, was still very much incomplete. So one of the first things the centre did was to bring together historians from all over Europe to basically establish a canonical historical record. How many victims, who, where? Why in 2016? Why is that date so important? Largely, it has to do with the first movements to bring Ukraine within the European Union.

In the 1990s, when the EU started to expand into Eastern Europe—with countries like Poland, Romania, Hungary, and others becoming candidates for membership—many of these countries came with a lot of baggage, especially concerning antisemitism. So the EU commission in Brussels decided that in some way this history needed to be dealt with straight on, making Holocaust remembrance one of the things that had to be properly organized before these countries could become members of the EU. For example, the 27th of January, which is the day of the liberation of Auschwitz, would be commemorated in each of these countries.

So in 2016, as Ukraine started moving towards a possible application for EU membership, it had to in some way get its Holocaust history in order. Which meant that it had to start to do something with Babyn Yar. Hence the creation of the foundation behind the centre, and the research and writing of the canonical historical narrative with basically a full accounting of the historical events in 1941.

There was also the decision to create a big museum, what would be the second largest Holocaust memorial museum in the world after Yad Vashem. They were very ambitious, despite the fact they had no collection yet. An architectural competition was held and the proposal that won, by an Austrian firm, was this enormous underground museum. You might think that an underground museum on a site where we don’t really know where human remains are might be a problematic idea. But this is the proposal that won.

Then, in 2019, the foundation got a new artistic director, the filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky. Khrzhanovsky, a rather controversial figure in Russia and Ukraine, believed the museum was a misguided project, and he killed it. While I do not always agree with Ilya, certainly I agreed with him on this.

Instead the foundation started working with an idea that was first developed by the architectural theorist and critic John Hejduk. Hejduk believed that a memorial structure should not simply be one big memorial, but a collection of memorials—fragments that basically relate to each other. Because when you're dealing with trauma of such magnitude, it’s impossible for a single piece to represent it. So, in a way, you divide it up and it’s in the relationship between these fragments that meaning can emerge.

He also argued that you should build it over time. You shouldn’t try to do everything in one single gesture, that you should basically give space to the next generation for further development. He called this “growing incremental place-incremental time.” The best expression of this idea was Hejduk’s proposal for the Topography of Terror site in Berlin, which was the Gestapo headquarters.

In the wake of the museum proposal’s collapse, the thinking started to develop in the spirit of Hejduk, to have a collection of smaller projects built over time, basically starting to mark pieces of this site.

Images clockwise: The Babyn Yar synagogue in Kyiv, designed by Manuel Herz and commissioned by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center; architect Herz at the synagogue's official opening; detail of the synagogue, including wall inscriptions and painted ceiling replicating the night sky on the first night of the massacre in September 1941; an earlier monument to the Jews massacred at Babyn Yar unveiled in September 1991. (Photos: Iwan Baan)

What does it mean when you try to create a representation of a site like Babyn Yar? In the case of Babyn Yar, we’re dealing with a legacy of destruction, not only of people but of cultural assets. One of the only major architectural traditions that Jews have ever created were the wooden synagogues in the Pale of Settlement—what is today parts of Russia, eastern Poland, Belarus and Ukraine—but all of them were destroyed. An incredible erasure of Jewish cultural memory. It became very clear that one of the first things we need to do, if we’re going to do anything, is consider the possibility of building a synagogue on the site.

It took us really only a minute to decide who the architect could be and that was Manuel Herz. Certainly Manuel doesn't want to be famous as a synagogue architect, but he is responsible for the best synagogue produced in Europe since the Second World War, the Mainz Synagogue, which opened in 2011. I literally crossed the ocean to see it when I heard that it had opened. It is an incredible masterwork.

MANUEL HERZ: It may seem inappropriate to invoke the toast L’chaim—to life—but nevertheless that was maybe a guiding idea when I received a telephone call in the fall 2020 from Ilya Khrzhanovsky, asking me if I wanted to design a synagogue at Babyn Yar. My son had just been born two weeks earlier and maybe that had put me in a certain direction or headspace, one that looked to the future. Of course, I was incredibly honoured to be asked, but also felt an incredible responsibility of how to act as an architect.

The Babyn Yar site is a very odd place. It is very much marked by the massacre and the horrific events that took place there 80 years ago, but as today it is a public park it is also a place of recreation, people riding bikes, a place of picnicking. Nearby is the headquarters of the main Ukrainian TV station. I don't know whoever came up with that idea, but there’s even a shooting range belonging to a private gun club. And there is the historic Jewish cemetery which still exists, and some commemoration of the massacre that seems quite programmatic. It's a heavy place loaded with so many layers of history, of massacres, but also layers of everyday life and banality. I was very happy that Robert’s idea that the synagogue would be one of the first in a series of smaller and mid-scale interventions.

In the ongoing history of commemoration of Babyn Yar, what I was asked to design was not a memorial per se, but a synagogue, because the synagogue is, in the end, about life. It’s about bringing Jewish life back to the place where it was eradicated 80 years earlier. Of course, the synagogue would also have commemorative functions and dimensions.

When we think of memorials that commemorate the Holocaust, we usually think of these quite heavy, somber structures. Like the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, just an ocean of concrete, and there are many others, quite similar structures, that are very heavy and often have a dedication or inscription you are supposed to read that gives you the kind of essence of what this memorial is about.

I thought that was the wrong starting point. We’re talking about a place that saw the massacre of almost 34,000 individuals, and then tens of thousands of more people in later weeks, who all had their own idea of how to live a life. This multitude of individuals whose lives vanished, were eradicated—I thought we can’t reduce that to a single slogan or inscription. The crime is so heavy that we can’t equate it with the heaviness of material.

I thought let’s do something that is maybe quite the opposite of these heavy structures—something that is maybe transformative, maybe performative, that engages visitors, brings them in, and doesn’t enforce a single viewpoint, but a multitude of viewpoints. That is multi-vocal, if that’s possible in architecture.

I was also thinking about books. That is not necessarily a surprising reference, I myself incorporated references to a book and writing in my design for the Mainz Synagogue. I thought maybe this is appropriate, we are, after all, the people of the book. But I wondered if there was something more interesting we could do to push the idea further.

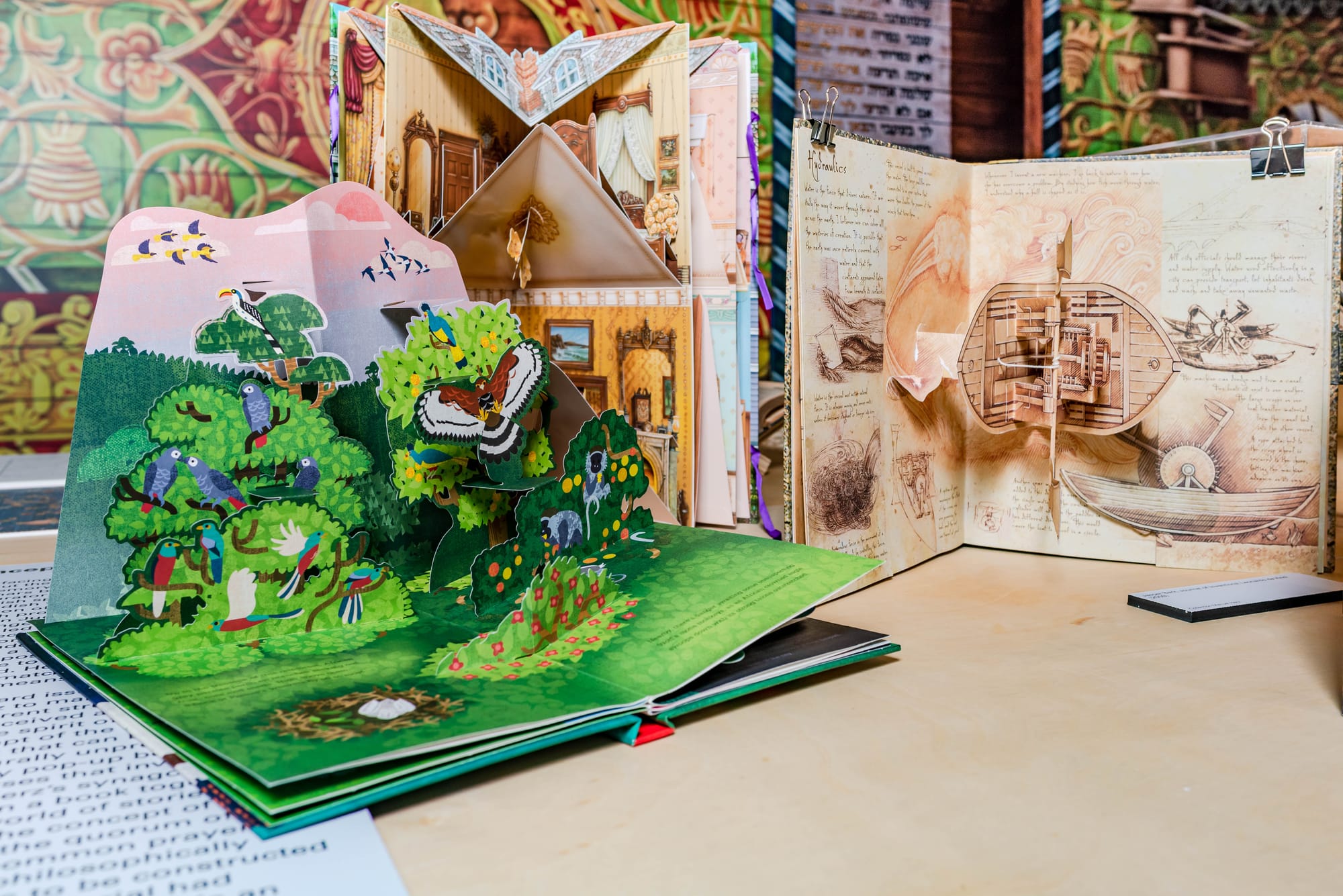

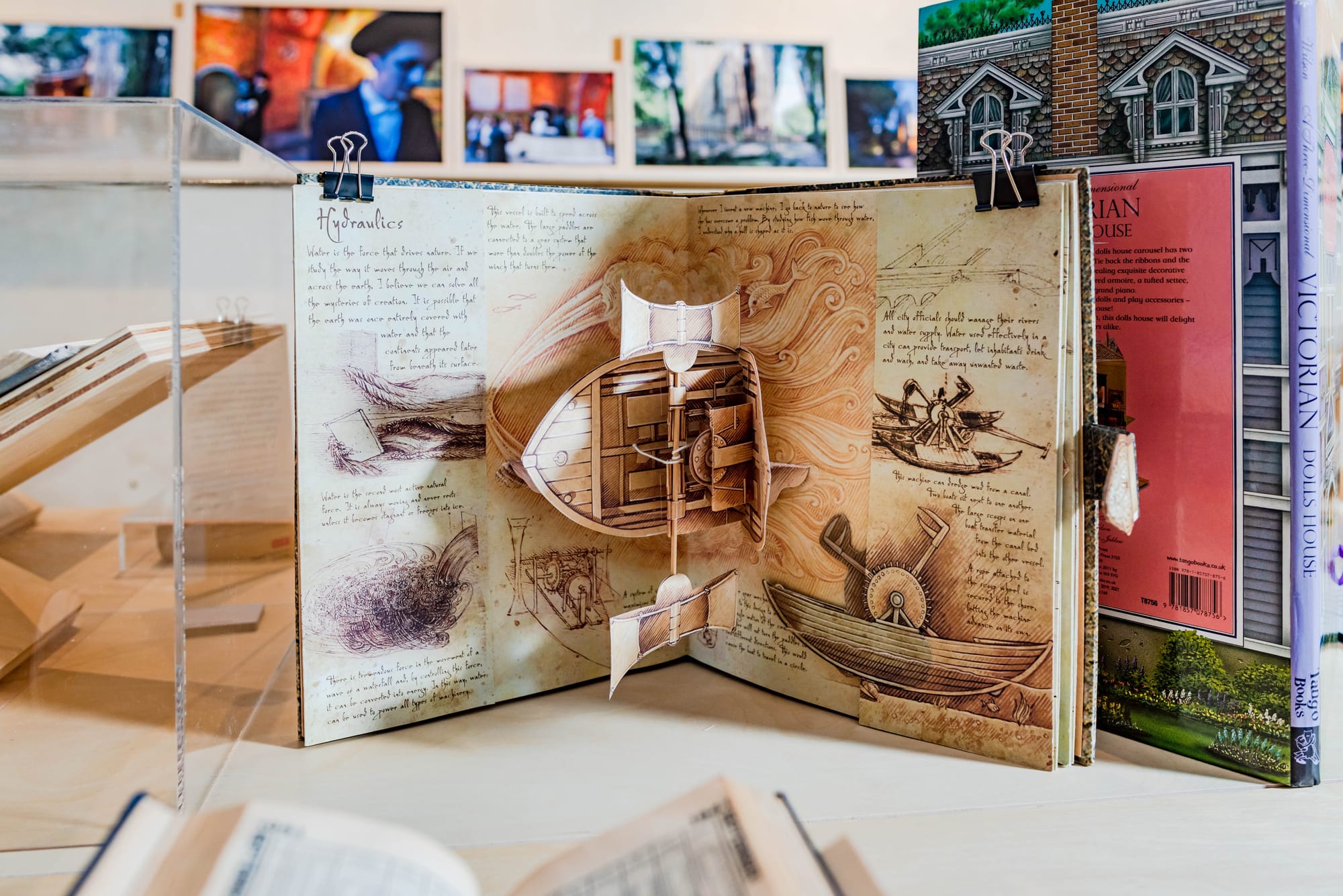

Samples of the sorts of pop-up books that inspired Herz’s synagogue design, as displayed on the curio table at the Koffler exhibition. (Photo: Rebecca Tisdelle-Macias)

Because of the birth of my son, I began thinking about pop-up books in particular, books that unfold from a slim volume into a three-dimensional world, where you put your nose in and get lost in the details of the imaginary space that has been created. In all seriousness, I thought, maybe this has something to do with what a synagogue is. Because what do we do in a synagogue? First of all, we are a group of people, the minyan, and when we go into a synagogue we open a book, the book of prayers, or other religious texts, and we read that book together. That book unfolds for us a universe of stories, morals, laws, sayings, history, loves, lives, and we get lost in it.

So I thought, why not do it quite literally, and make a building that really opens up, that also enlights the public. A synagogue that is as open as you can make it.

We started building in late January, early February, 2021. The ground was frozen. The ground is incredibly important because the ground has seen so much death. And it was constructed by these wonderful craftsmen, builders, engineers, whose faces almost seem familiar to us now because we see them on TV fighting on the front against Russia. It was built within the fastest amount of time, three months. In April, the wooden building itself was finished.

There were two details that were quite important for me, both in terms of construction and the conceptual approach. First is how the building slightly hovers above ground. This was quite a technical challenge but it was incredibly important for us. We certainly didn’t want to disturb that ground which has seen so much death, where you may find actual bones. So we made sure that the building itself hardly touches the ground. The other thing is its wooden materiality, in a way that stands counter to almost all other commemorative and memorial structures that we know.

With concrete, you can create something and leave it there for generations and it almost doesn’t change. Maybe there’s a certain kind of sincerity or security that it gives you, but it’s also almost an opportunity to forget about it. Whereas building with wood, it introduces a certain kind of fragility into the structure. Where every day you need to take care of it, you need to oil it, you need to clean it, you need to treat it, repair it, protect it. That kind of everyday care is maybe also a kind of commemoration in practice. I thought contrary to what we usually think, maybe wood goes much more to the core of what commemoration should mean in architecture than any kind of stone or concrete materiality.

ANTHONY SARGENT: The last week of November 2022 I was talking to the philanthropist Carol Weinbaum about possibly supporting an educational project, and she asked, “Would you mind if I suggested something different to you? This extraordinary thing has just come into my life in the last few days and it has excited me very much.” She told me the extraordinary story she’d heard at a recent dinner about Manuel’s synagogue. Would I be interested in the possibility of an exhibition telling the story of this amazing synagogue and its journey?

The first thing she did was connect with Robert Jan van Pelt, and during the first week of December we talked about the synagogue and how an exhibition might be framed around it. At first I thought he would be the historian and we’d have to bring on board a curator. But it very quickly became clear that he wasnt just an extraordinary historian, he was a great thinker in all kinds of ways, and possessed some very considerable curatorial skills of his own.

The second week of December I spoke with Manuel Herz for the first time. So there’s three of us now. Very quickly we had the idea of how you might tell this story in an exhibition, at a space like the Koffler Gallery. A few days after the three of us had our first conversation, almost incredibly looking back on it now, we had the first draft of the project plan. It changed extraordinarily little from that moment on.

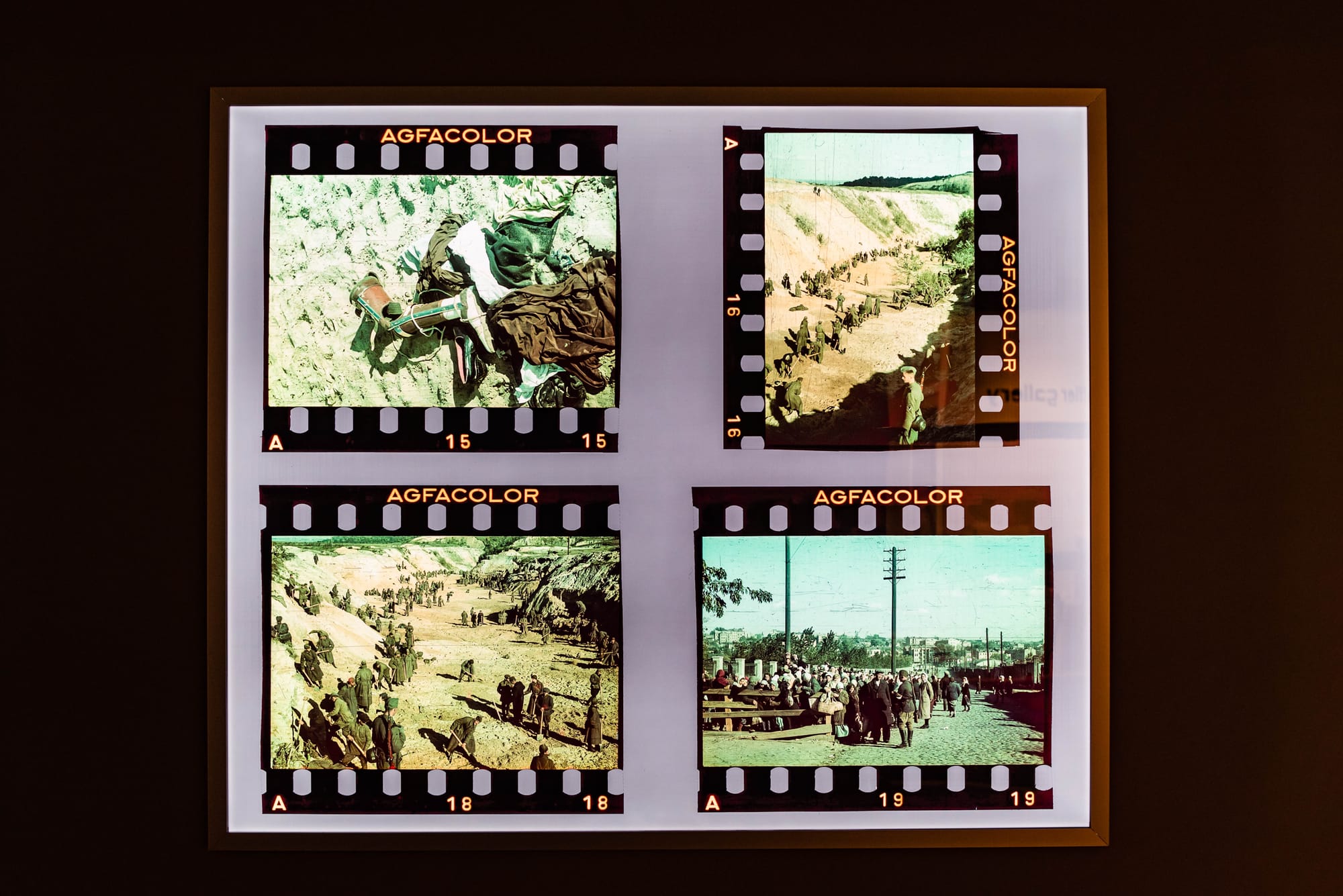

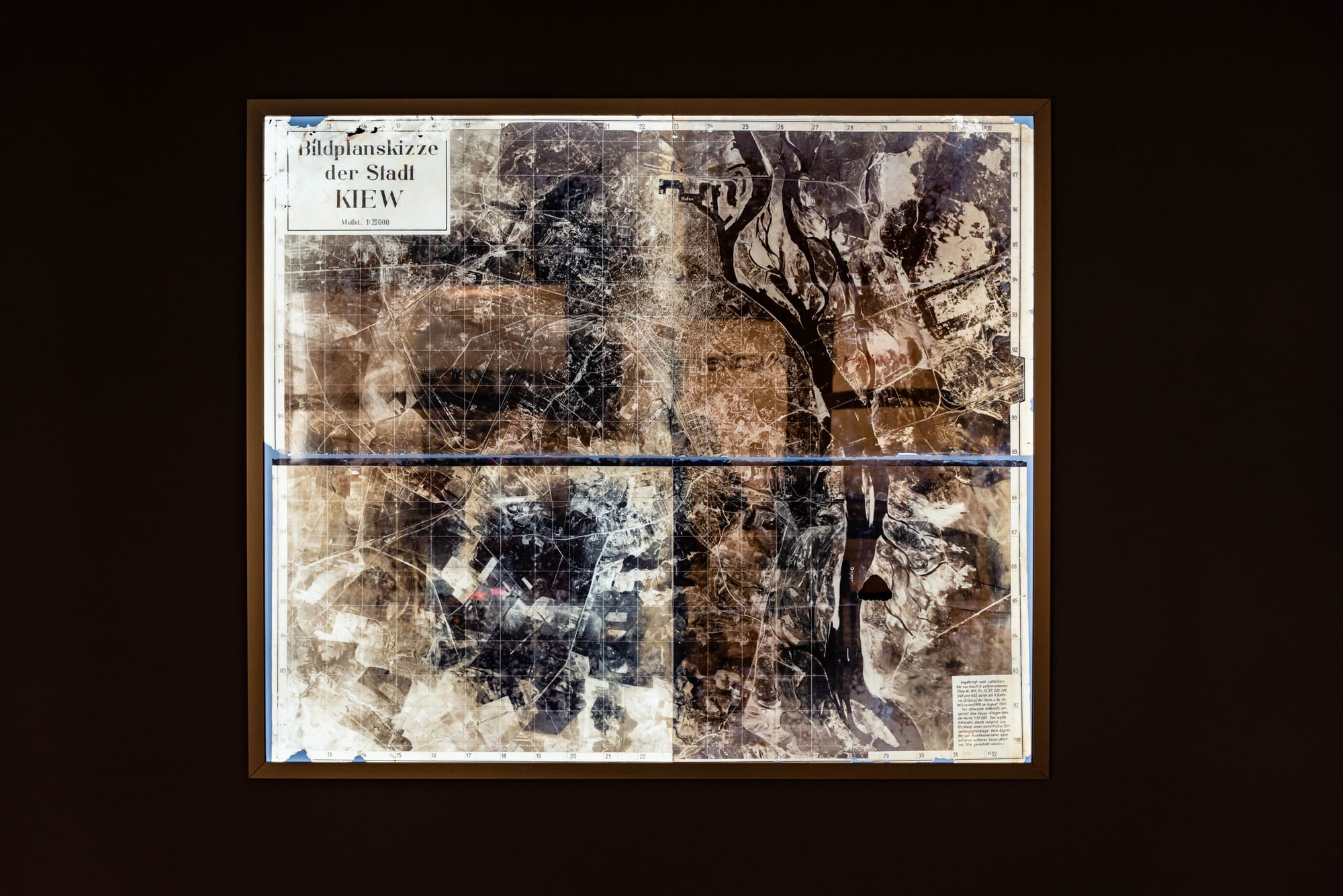

Lightbox images at entrance to the exhibition. At left, images showing Soviet POWs forced to bury victims in the days following the massacre. At right, the aerial map of Kyiv used by the Germans at the time of their invasion. (Photo: Rebecca Tisdelle-Macias)

But one of the first challenges pushed in front of me was that they were both obsessively committed to the notion that if we did this project, it would open on the eve of Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, which would be the 17th of April. I told them you cant possibly put together an exhibition at that speed. Manuel Herz rather dryly said, “Well, we put together the synagogue at an unbelievable speed. Why cant we do the same with an exhibition?”

About a week after that we brought Douglas Birkenshaw on board to install and help design the show. Obviously, Manuel couldn't supervise the physical construction of the exhibition from Basel, and it wasn't particularly Robert Jans expertise. We needed somebody to be the physical producer of the exhibition, and the role didnt quite relate to the normal roles you would have in a fine arts exhibition, where you'd have a curator and the artist. This show didn't work quite like that. We had this team of four of us. Robert Jan was the historian, the curator, the thinker, the creator of the narrative for the show. Manuel Herz, having designed the synagogue, felt it was natural for him to broadly design the look and feel of the exhibition itself. Douglas Birkenshaw was going to be the man who would realize it and make it happen.

We were just like four tradesmen, there was a wonderful sense of democracy amongst us. We very quickly agreed on what was the right solution and the right solution wasn't always the perfect one. The right solution would be the one you could achieve in two weeks. There were compromises. Lots of people have said to me, if you’d had the usual two years, I’m sure it would have been a very different show. But actually, I don’t know that it would. We made decisions very fast, but I still think they were pretty good decisions. Looking back on them now, there are very few that I would revisit.

How do you tell this story through physical artifacts that the public can see and engage with?

What is the most compelling way of telling this story through a visual landscape that the public can walk through? That’s a different kind of question to ask from how do we represent the work of this great sculptor? How do we represent the work of a great photographer? We had to find a way of making this show that was more like the performing arts. We didn’t treat it like a fine art show. We treated it in a way more like an installation that a figure like Robert Wilson might create.

DOUGLAS BIRKENSHAW: Robert Jan van Pelt and I had worked together before. The first time was around 1997, when Robert was asked to do a master plan for the site of Auschwitz—this was when the Polish government was still somewhat embarrassed by its presence and kind of ignoring it, meanwhile millions of people were showing up to see it. So we designed the first three models for the site based on his masterplan. Later we worked together again, when I helped Robert with his Evidence Room exhibition, when it was being presented at the Hirshhorn Museum.

When I first heard about the Babyn Yar project I knew the timeline was relatively compressed—at that time they were planning on opening in November 2023, then Anthony said, “Well, we actually need to open in April.” I thought we could still do it as long as there wasn’t any slack in the process. I sketched out a few ideas for the space and interestingly enough, Manuel had a very similar idea for the space, which was, to start, simply surrounding the visitor with very large murals on the walls.

One of the exhibition's large photographic murals depicting the ravine at Babyn Yar today, photographed by Maxim Dondyuk and directed by Ed Burtynsky. At right, the map created by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center to indicate the ravine's original contours, now largely filled in. (Photos: Rebecca Tisdelle-Macias)

We also liked this thing that Manuel had done to show his hospital in Senegal, when he presented the project at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, with basically this curio table displaying objects that were curated in some fashion but still quite loose—you could either spin through it all in ten minutes or spend an hour-and-a-half reading everything.

It moved quite quickly forward from there, developing ideas and concepts about how to present the various pieces of work. Then as soon as everything was sort of settled in one area, I would go and get it priced and start getting it made.

The only reason we had this idea for the murals is that the walls existed and we wanted something that would have a great deal of power, and was also something we could put up quickly. Then Anthony says, “I’ve been talking to Ed Burtynsky and he’s interested in getting involved.” Given the war in Ukraine, Ed would collaborate with and direct from Toronto the Kyiv-based photographer Maxim Dondyuk. We had no idea what the murals would actually be, our first sort of concept was they would actually be out in the park itself.

Then as the Kyiv-based photographer Maxim Dondyuk was sending images back it became quite clear that the images of just the ravine were more powerful, you have this poetic quality of the trees growing out of the bones of the dead.

Originally we were going to commission someone to make the model of the synagogue, then someone from the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center sent us a photograph of this thing that they’d been working on—this five foot by five foot by five foot model. It’s a serious object. We just kind of gambled that we’d manage to get it here on time.

That was a whole ordeal. First of all, you couldn’t get it directly out of Kyiv. So Manuel managed to find somebody there who would put it on a truck for X amount of dollars and drive it up to Warsaw, which they did. From there I organized for it to be sent here by FedEx. Then as soon as it’s in FedEx’s system, immediately I get a message telling me that there’s a problem. Now it’s just sitting in some warehouse in Warsaw, and of course nobody at FedEx has any idea what the hell’s going on. The date of its arrival keeps getting pushed back, and we’re getting closer to opening day. Then a thing pops up on my screen saying it’s in Mississippi. Then it’s stuck in Mississippi forever, until one day it suddenly shows up in Toronto.

It’s an interesting show because what is the show, what is it actually about? Is it about the synagogue or the event? Of course it's about both. The opening scenarios—the lightbox images of Russian POWs burying the dead two days after event, the interpretive text, the map showing in red the original contours of the ravine—and then the wall murals showing the ravine today, these are all about context and location, but in a poetic way. They describe very clearly the physical aspects of the horror

The curio tables are really more a kind of an illustration of how an architect like Manuel might work. It describes, in a non-linear way, how certain ideas come up—like the pop-up books, the tallit knitting from prayer shawls that are referenced in the synagogue’s columns, literature written about the massacre at a time when it was being ignored, the history of wooden synagogues, or the bestiaries that inspired the decorations on the synagogues walls.

All of that was really interesting to me because it’s usually quite hard for architects to describe their process. Usually they’re bad at it and overly glorify it. The curio table culminates in a series of working drawings for the memorial and the model.

In the end, the show is not really about the event, or the synagogue, but about how we memorialize the event.